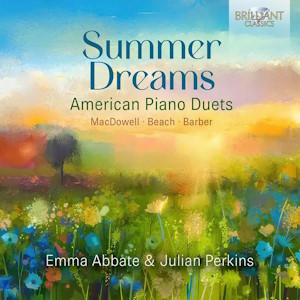

Summer Dreams – American Piano Duets

Edward MacDowell (1860-1908)

Three Poems Op.20 (1884)

Moon Pictures Op.21 (1884-5)

Hamlet and Ophelia Op22 (1894)

Amy Beach (1867 – 1944)

Three Movements (1883)

Summer Dreams Op.47 (1901)

Samuel Barber (1910 – 1981)

Souvenirs Op.28 (1952)

Emma Abbate, Julian Perkins (piano)

Justine Marler (narrator: Summer Dreams)

rec. 2022, St. George’s Bristol UK

Brilliant Classics 97118 [78]

This is an attractive recital – generous, sensitively and well-played – of less familiar American music for piano four hands. Very roughly half of the total playing time of 78:20 is devoted to music by Edward MacDowell all of which receives first recordings. I did not know the Amy Beach works before and the Samuel Barber I had heard in its (later) orchestral version only.

Peter Quatrill in his useful liner note makes the valid point that both MacDowell and Barber were pianists of considerable stature themselves as well as composers and had written virtuoso works to showcase their abilities. However, the music offered here was aimed at the large and lucrative 19th Century domestic market for piano-duet music. The prospect of sitting intimately close to someone on a piano stool probably outweighing more cerebral or artistic considerations. So the requirements of this music were that it should be technically and aesthetically accessible rather than having any great intellectual or emotional goals. Both the composers and the performers here – Emma Abbate and Julian Perkins – are wholly successful allowing this essentially simple music to speak directly without artefact or over-emoting. Beach’s Summer Dreams were published in 1901 but the rest of the Beach and MacDowell works mainly date from the 1880’s. The individual movement titles of the Macdowell Three Poems and Moon Pictures as well as the Beach Summer Dreams reflect the narrative/often naively illustrative nature of the music with the relative brevity of the movements – most lie in the 2- 4 minute range – underlining the modest intentions of the music.

But that said they are without exception beautifully crafted and very attractive. The intended domestic setting and the often lush and rich writing suggests that the music is written to give pleasure to the performers as much as any audience and certainly that is how it sounds here. The recording in St. George’s Bristol is quite close but the Steinway Model D sounds suitably resonant and warm-toned. The playing of Abbate and Perkins is unforced and understatedly fine – just as the music requires. I must admit that my reaction to the MacDowell pieces is much the same as I have had to all of the music of his I know. In the moment of listening it is easily appealing but somehow there is a lack of individuality to his compositional voice that makes me struggle to ‘recognise’ his music or for it to linger long in the memory. Of course part of the issue is that MacDowell (or Beach for that matter) had no interest in finding a uniquely American/Nationalist musical voice. Musical America of the 1880’s was wholly Euro-centric with German composers and performers/conductors the ideal. So no real surprise that these piano works sound quite as Germanic as they do. Hamlet and Ophelia is the exception. This is a thirteen and a half minute two part orchestral tone-poem transcribed by the composer. The original can be heard on a Naxos disc from Takuo Yuasa and the Ulster Orchestra who make as good a case for the Tchaikovskian drama as can be imagined. Similarly Abbate and Perkins respond with a performance more overtly virtuosic and flamboyant but the nagging doubt remains that this is sub-Tchaikovsky. By some distance this is the most substantial work on the disc – the two sections, one for each character – are individually tracked but the total running time is around 13:30. Crudely put Hamlet is muscular and dynamic and Ophelia lyrical and pensive.

Amy Beach’s Three Movements are striking for the simple reason that she was just sixteen when she wrote them. Yes they too are stylistically wedded to German models but there is a confidence and skill in the writing that is wholly impressive. The Summer Dreams reflect the increasing maturity of the composer. Quantrill suggests that they were not written for children to play but instead as character pieces for children to hear – the dedication to the composer’s niece might suggest just such a function. Each of the six brief movements is prefaced by literary quotations. Curiously, Brilliant Classics have chosen to include these quotations spoken before each piece is played but not individually tracked. Here the words are spoken lightly and with an appropriate-feeling slight American accent by Justine Marler. However, for repeated listening there is no way I want to hear these slightly twee and fey texts every time. The authors might include Shakespeare and Whitman (and Beach herself) but there is nothing in the printed score – viewable on IMSLP – to suggest they are meant to be read in performance. A curious production choice that I think is a mistake. However, the playing of these attractive character pieces is every bit as good as before and this collection is an excellent example of this type of “for children” work.

Jump forward nearly half a century for the disc’s concluding work – Samuel Barber’s Souvenirs written at the suggestion of a pianist friend Charles Turner – to whom the work is dedicated. Barber was suffering from composer’s block so Turner suggested; “why don’t you write a party piece, something we can play at parties”. Once composed, Barber sent this explanation to his publishers which Quantrill reproduces in the liner; “One might imagine a divertissement in a setting of the Palm Court at the Plaza Hotel…. the year about 1914, epoch of the first tangos, Souvenirs – remembered with affection, not in irony or with tongue in cheek, but in amused tenderness.” The work comprises six dances – tea dances perhaps? – which have that delightful feeling of wrong-note harmony and melody that prevents the music from sinking into sentiment while bringing light and air and wit to it. All qualities that are very evident in the sparkling and affectionate performance it receives here from Abbate and Perkins. Again Barber was no Nationalist composer but here the influence is Gallic – specifically Poulenc perhaps – rather than Germanic. Given the instant appeal of this music no surprise that it exists in multiple versions but I had not encountered this piano four hands original before and it is a delight.

All of the music on this disc is intentionally slight but it all receives performances of genuine insight and considerable musical and technical skill. This allows for a pleasurable and undemanding hour or so of listening.

Nick Barnard

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI and helps us keep free access to the site