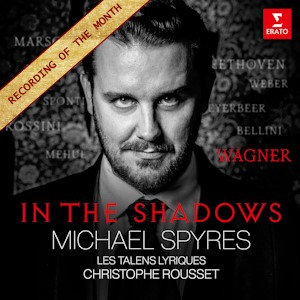

Michael Spyres (tenor)

In The Shadows

Le Jeune Chœur de Paris, Les Talens Lyriques/Christophe Rousset

rec. 2022, Salle Colonne, Paris, France

Sung texts (French, Italian and German) with English, French and German translations

Reviewed as lossless WAV download

Erato 5419787982 [84]

Michael Spyres, now in his mid-forties, has been one of the foremost tenors in the bel canto repertoire for quite some time now, and there are no signs of vocal deterioration – quite the contrary to judge from this highly interesting recital. The title, “In the Shadows”, could indicate that some of the ten composers – Méhul, Auber, Spontini and Marschner – are quite obscure nowadays, but the rest are certainly not forgotten. No, the shadows refers to the fact that the young Richard Wagner found a lot of inspiration through listening to the music of these predecessors. Copy them he didn’t; he was too independent for that, but he learnt a thing or two from each and every one of them. It would of course be an interesting adventure to dig deep in each of the arias and find sources to Wagner’s early works, but it is also fully valid to regard this as a normal recital with arias from twelve 19th century operas that once were immensely popular and/or important trend-setters. I have chosen the latter alternative.

The oldest of these composers was Frenchman Méhul, called the first Romantic and the leading French composer at the time of the French Revolution. His greatest years were before the turn of the century 1800, but he lived until 1817, and Joseph en Égypte was premiered in 1807. It became very popular, particularly in Germany, and has narrowly escaped being totally forgotten. At least the aria Champs paternels has survived and been recorded. I have long treasured a DG recording with the marvellous Canadian tenor Leopold Simoneau – an extremely lyrical singer, but with deep involvement. He is best remembered as one of the best Mozart tenors after the war, but he also sang Don José, Faust and Hoffmann in the recording studio. Michael Spyres has a larger voice, but he scales it down to the same lyrical sensitivity as Simoneau – but he also has the heft for the dramatic moments, where Simoneau, in spite of his admirable intensity, is a little at a loss. Both readings are utterly convincing.

Florestan’s touching aria, that opens the second act of Beethoven’s Fidelio, has been sung by lyrical tenors like Ernst Haefliger and highly dramatic Heldentenors like Jon Vickers – in both cases with considerable success. Spyres encompasses both capacities and is more beautiful than either. I have a soft spot for Gösta Winbergh in the role, but Spyres is certainly marvellous too.

Rossini’s Tudor opera, Elisabetta, regina d’Inghilterra is a true bel canto opera, and Spyres sings so softly at the end of the opening recitative in this long scene, and the aria proper, Sposa amata, in three-quarter-time with exquisite accompaniment is overwhelmingly performed. The wide downward leaps cause him no problems. He sometimes calls himself a baritenor; here he is almost bass-. tenor. It is indeed impressive.

Meyerbeer is best known for his French grand operas, which set the tone for this genre, but he also wrote operas to German and Italian texts. Il crociato in Egitto was the last of his Italian operas, composed in 1824, and is supposed to be the last opera written for a castrato. The aria is of bel canto type with trills – I need hardly say that they are expertly negotiated – and the singing is beautiful and filled with nuances. Spyres also undertakes an impressive journey down into the bass register.

Max in Der Freischütz is another role that is sung by both lyrical and dramatic tenors. Carlos Kleiber employed Peter Schreier for his DG-recording, and a dozen years ago I heard Colin Davis conduct a concert version at the Barbican with the mighty Simon O’Neill as Max. Like O’Neill, Michael Spyres has the power, steel and intensity for the opening Nein, länger trag’ ich nicht die Qualen, which Schreier couldn’t muster, and he also surpasses Schreier in mellifluousness and warmth in Durch die Wälder, durch die Auen. O’Neill was actually very good in that respect as well.

Auber’s La Muette de Portici has claims to be the first grand opera, premiered in 1828, the year before Rossini’s Guillaume Tell, and three years before Meyerbeer’s Robert le diable. Masaniello’s aria is allegedly tricky to sing with its high lying tessitura, but Spyres sings it elegantly and relaxedly.

Spontini was an important figure during the first decades of the 19th century. His most well-known work is no doubt La Vestale (1807), an aria from which was recorded by Rosa Ponselle during the 78rpm era, and in the 1950s it was successfully staged at La Scala with Maria Callas and Franco Corelli. Agnes von Hohenstaufen was his last opera, premiered in 1829. It has also been revived in recent times, and my only previous encounter with it is a soprano aria, which was included in Anita Cerquetti’s only recital disc from the mid-1950s. Heinrich’s aria, recorded here, is a world premiere recording in the original German. Michael Spyres’ singing here is luminous, and his voice has an innate beauty that ennobles the music.

Pollione in Bellini’s Norma is a role requiring a high dramatic voice and singers like Placido Domingo, Giuseppe Giacomini and Franco Corelli have excelled in the role in complete recordings. Michael Spyres has a leaner voice and sings the aria with unforced lightness, but still has the dramatic heft – even though he doesn’t have Otello force of Giacomini and Domingo and the baritonal darkness of Corelli. It would be interesting to hear him in a complete version of the opera, bearing in mind that he has an impressive downward extension of his register.

Hans Heiling becameMarschner’s most popular work, although Der Vampyr also attracted large audiences. In both works there are supernatural elements and neither of them belongs to the standard repertoire, but both contain attractive music, and the aria heard here is very beautiful and sung with fine legato.

The recital concludes with “the real thing”, Wagner himself in three early works. Well, “real thing” it isn’t, at least not in the two first items, but it is interesting to have the earliest of them, from Die Feen. The Rienzi aria is fairly often heard in recitals and Lohengrin is of course the most popular of Wagner’s ten mature operas. But the singing style is still a far cry from Tristan and the Ring operas. Spyres sings Mein lieber Schwan to the manner born – masterly indeed – with lightish tone and reminds me of Klaus Florian Vogt, and from an earlier generation Nicolai Gedda who sang a couple of Lohengrin performances at the Stockholm Opera in the mid-sixties.

I really enjoyed this programme for two reasons: for the partly unhackneyed repertoire, and for the marvellous singing throughout. Michael Spyres is certainly one of the foremost singers of today, whether he is called tenor or baritenor. I am now looking forward to his next excursion along more untrodden paths in the more or less forgotten operatic brushwood.

Göran Forsling

Help us financially by purchasing from

Contents

Etienne-Nicolas Méhul

1. Joseph en Égypte, « Vainement Pharaon… Champs paternels

Ludwig van Beethoven

2. Fidelio, « Gott! Welch Dunkel hier!… In des Lebens

Gioacchino Rossini

3. Elisabetta, regina d’Inghilterra, « Della cieca fortuna… Sposa amata… Saziati, o sorte ingrata ?

Giacomo Meyerbeer

4. Il crociato in Egitto – « Suona funerea

Carl Maria von Weber

5. Der Freischütz – « Nein, Länger Trag Ich Nicht

Daniel François Esprit Auber

6. La muette de Portici- « Spectacle affreux …

Gaspare Spontini

7. Agnes von Hohenstaufen, « Der Strom wälzt ruhig seine dunklen Wogen

Vincenzo Bellini

8. Norma – « Meco all’altar di Venere…Me protegge, me difende (with Julien Henric (tenor))

Heinrich Marschner

9. Hans Heiling op. 80 – “Gonne mir ein wort der Liebe”

Richard Wagner

10. Die Feen WWV 32 – « Wo find ich dich, wo wird mir Trost?

Richard Wagner

11. Rienzi, der letzte der Tribunen WWV 49, « Allmächt’ger Vater, blick herab

Richard Wagner

12. Lohengrin WWV 75, « Mein lieber Schwan