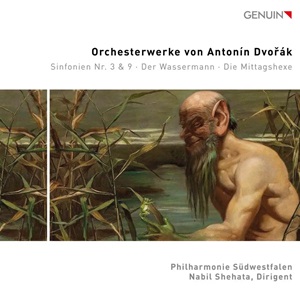

Orchestral Works by Antonín Dvořák

Antonín Dvořák (1841-1904)

The Water Goblin, Op 107 (1896)

Symphony No 3 in E-flat major, Op 10 (1873)

The Noonday Witch, Op 108 (1896)

Symphony No 9 in E minor, Op 95 ‘From the New World’ (1893)

Philharmonie Südwestfalen / Nabil Shehata

rec. 2021, Stadthalle Betzdorf, Germany

Genuin GEN 24853 [2 CDs: 115]

Prior to listening to this pair of discs, I had not encountered the work of conductor Nabil Shehata. Clearly he is a musician of the highest stature. He was appointed principal double bass of the Berlin Staatskapelle and followed that with four years in the same post with the Berlin Philharmonic. But by his late 20s he decided to pursue a career as a conductor and since 2019 he has been principal conductor of the Philharmonie Südwestfalen that appears on this disc. As with many of these German regional orchestras the playing standard, both collectively and soloistically, is very high indeed and a great deal of pleasure can be taken from hearing fine and sympathetic playing of great music, well recorded.

But of course the field of Romantic Symphonic music is very crowded and the works of Antonín Dvořák are very well represented indeed in the catalogue. So it is hard to know quite where this pair of discs – currently retailing in the UK around the £23-26 mark – fits. The discs run to a total of about 115 minutes, with each pairing one of the late great Erben-inspired tone poems with a symphony. To be clear, all four works receive intelligent, well-played performances recorded with attractive clarity and bloom by the Genuin engineers. Indeed, a concert-goer would be very happy to have heard any of these versions live. However, the virtues of good taste and musical sanity do not necessarily make for compelling repeated listening.

There is an argument to say that all four works represent Dvořák the dramatist. In the midst of the melodic richness, formal skill and orchestral beauty, there is inherent drama and expressive power that tends to be smoothed away here. The two Erben tone poems; The Water Goblin [Der Wassermann], Op 107 and The Noonday Witch [Die Mittagshexe], Op 108 are a case in point. Written in the mid 1890s when Dvořák was at the height of his considerable powers, these are a virtuoso fusion of symphonic form, graphic illustration through music and the use of melodic shapes dictated by poetic texts. Only a truly great composer would be able to combine these disparate elements into such effective extended works. Key to their effectiveness is the sheer gory drama of the poetic originals. These are not cosy happy-ever-after fairytales, but stories of malevolent supernatural encounters represented in music of sharp contrasts and clearly etched detail. Shehata has an expressive but slightly smoothed-out style which emphasises lyricism at the expense of contrast. For sure, there is a dynamic range, but Dvořák peppers his scores with an extreme range of dynamics, articulations, tempi adjustments and the like. Almost at random, page 24 of the miniature score of the critical edition of The Noonday Witch – a total of just 16 bars – shows 3 tempo adjustments, dynamics from ppp to ff with accents or tenutos and fz appearing in six bars. I would suggest that by ear alone, the listener to these new performances would struggle to identify that degree of detail. The Genuin recording is very good as mentioned – internal orchestral detail registers very well. Percussion – not exactly a major feature of any Dvořák score – is crisp and clear [a good example is the quietly menacing tam-tam near the end of The Water Goblin], the lower end of the orchestra registering with attractive warm fullness and the brass choir are well-balanced and rich-toned.

There is a performing tradition in Dvořák that sees performers adding various tempo adjustments not indicated in the original scores. Many of the classic Czech recordings are prone to these ‘traditional’ amendments, but Shehata steers well clear of most of them. To the point where it can feel quite straight interpretatively. That a direct and unfussy approach can work well was proved in a recording I reviewed some years ago on the SWR music label with Karel Mark Chichon conducting the Deutsche Radio Philharmonie Saarbrüken Kaiserslautern. The parallels of a skilled regional German orchestra sympathetically recorded are notable. But to my ear, Chichon balanced the path of simplicity and direct expression with sensitivity and subtle phrasing to greater effect than Shetata. This was apparent when comparing the two performance of the Symphony No 3 in E-flat major, Op 10. As I wrote in my earlier review, the work marks several important milestones in the composer’s career. Dvořák was still earning his keep as a player in the opera. This was the piece he presented as a sample of his work to obtain a State grant – sponsored by Brahms – that would allow him to focus on composition alone. It is one of his most compact symphonies – in part being because it is in three movements – a unique feature amongst Dvořák’s symphonic cycle. The Editio Supraphon critical edition suggests timings of 9:30, 14:10 and 9:20 whereas Shehata comes in at 11:46, 16:12 and 8:21. While timings alone can be a crude measure here, they do accurately reflect a relaxed opening Allegro moderato, a rather grand and stately Adagio molto, tempo di Marcia and a genuinely sparkling closing Allegro vivace. In fact, very few of the accepted standard recordings of this work get near the first movement’s recommended duration – Kubelik, Rowicki and Kertész are all very close to Shehata. In fact only Anguelov on Oehms breaks the 10:00 barrier but in doing so the music gains a vivacity and sparkle that is very effective. Individuals will need to decide whether the emphasis should be more on “allegro” or “moderato”. Chichon is a good minute quicker than Shehata in the opening movement and then a handful of seconds swifter in the remaining two movements. One thing that is clear across all of these performances is just what an impressive work this symphony is. The stature of the last three Dvořák symphonies does mean that the earlier works have been relegated to the role of ‘lesser’ creations. In context that might well be true, but it should be noted that early Dvořák still surpasses the finest music of many a contemporary second tier composer. This is evident in this well-prepared and skilfully played performance, but other versions do reveal even more character and personality than here.

If Symphony No 3 remains relatively under-appreciated, then Symphony No 9 ‘From the New World’ belongs to that handful of classical works that have become stalwarts of every concert season, orchestra and music broadcaster. There is a French language website that lists over 600 commercial performances and recordings, although that appears not to have been updated in the last five or so years. So a conductor/record label must balance the ‘saleability’ of such a popular work with the sense that it has all been done before. No real surprise to note that Shehata’s basic approach is sane and well-prepared, with little or no indulgence or expressive extreme. He does allow the tempo to relax into the famous flute 2nd subject, but he chooses not to take the exposition repeat, which I must admit I prefer to hear. Not that any performance should be notable or commended for simply being different, but there is something rather generic about Shehata’s interpretation. There is nothing at all to be offended or surprised by, but conversely nothing to excite or engage away from the sheer quality of the execution. This is such a popular work that it is easy to forget just what a remarkably skilled piece of composition it is. Away from the gorgeous melodies and beautiful orchestration, Dvořák’s handling of his musical material is so deft and sophisticated that the listener is likely to overlook his use of cyclical thematic development and transformation. These are not just good tunes, they are brilliantly handled too. Add to that as well a sense of high drama too. There might not be any programme to this work, but the outer movements especially are full of incident and excitement. Compared to my favourite versions – Vaclav Neumann’s powerfully characterful analogue recording with the Czech PO or James Levine’s red-blooded Chicago Symphony Orchestra performance on RCA readily jump to mind, again I find Shehata to be just too safe and well-mannered. Dynamics are tempered and everything is just rather too predictable. Because this is a wonderful work, and it is well-played here, there is of course much to enjoy. I am not sure why this repertoire was chosen to showcase what is clearly a good relationship between orchestra and conductor, as on the evidence of this pair of discs Shehata has few special insights to offer regarding this composer.

Ultimately, a well-prepared and well-executed set of performances that lack the individuality or musical insights to command attention in a crowded field.

Nick Barnard

Help us financially by purchasing from