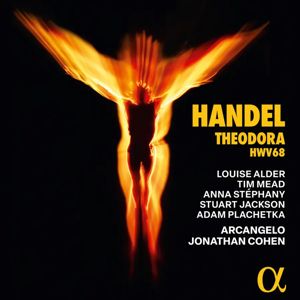

George Frideric Handel (1685-1759)

Theodora, HWV68 (1750)

Louise Alder (soprano) – Theodora

Anna Stéphany (mezzo-soprano) – Irene

Tim Mead (counter-tenor) – Didymus

Stuart Jackson (tenor) – Septimius

Adam Plachetka (bass-baritone) – Valens

Guy Elliott (tenor) – Messenger

Arcangelo/Jonathan Cohen (harpsichord)

rec. 2023, St Augustine’s Church, Kilburn, London

Libretto included

Alpha Classics 1025 [3 CDs: 178]

Just over a year ago I reviewed the starrily-cast but mediocrely-sung Theodora directed by the erratic Maxim Emelyanychev. Lisette Oropesa, Joyce DiDonato, Paul-Antoine Bénos-Djian, Michael Spyres and John Chest all failed to convince me – though in all fairness they convinced others – that they formed a stylistically cohesive unit who had thought seriously about questions of ornamentation, to take just one amongst other matters. In fact, privately I thought it a poorly assembled job lot of singers allied to a show-off orchestra and a conductor subject to fits of the vapours.

Now comes a proper recording from serious, musical singers, an orchestra strongly versed in the milieu directed by a conductor who knows precisely how to gauge and measure each orchestral effect. The result is a reading in which depth, gravity, tragedy and ultimate consolation are always foremost and in which tricksy decorations, explosive orchestral gestures, and a general air of triviality are wholly absent.

Cohen had performed Theodora at the Proms in 2018 with Louise Alder in the central role. The ensemble took Theodora to the Barbican on 29 March 2023 and recorded it shortly afterwards. Michael Mofidian was the original Valens but was replaced for the Barbican performance, and this subsequent recording, by Czech bass-baritone Adam Plachetka. The ensemble, vocal and instrumental, might have sounded a little small-scale in the Barbican – I don’t know as I wasn’t there – but it certainly doesn’t in St. Augustine’s Church, Kilburn in London. Finely sprung and buoyant, Arcangelo’s incisive playing is always a pleasure to hear – listen to the trumpets of Neil Brough and Paul Sharp in the chorus And Draw a Blessing Down and note – these are two small examples – the astute use of organ and harpsichord continuo.

Valens’ first recitative and aria, Go, My Faithful Soldier draws from Plachetka a saturnine menace, with a profuse use of the no-nonsense rolled ‘r’ and he shows in his vengeful aria Racks, Gibbets, Sword and Fire that he has the range, the breadth and the ‘face’ for the role, allied to which he has sensibly not over-decorated. Didymus is Tim Mead whose countertenor is focused and who again refrains from exaggeration, remaining unswervingly musical throughout, and is fluency itself in The Raptur’d Soul Defies the Sword. Mead is a decade younger than Robin Blaze, who might have been considered for the role a few years back whilst Iestyn Davies sang it at the 2018 Prom performance, but Didymus sits quite comfortably for Mead’s voice, and arguably a little better than it did for Davies.

The central role, as in 2018, is taken by Louise Alder whose subtle changes in tone colour and disdain for fleeting gestures remain splendid and just servants of the music. In her Act II aria With Darkness Deep as is my Woe her intimacy is both touching and psychologically penetrating, her trills are bright and precise, to which Cohen responds with lucid, articulate string phrasing. This is again a feature of O That I on Wings Cou’d Rise where the answering string phrases are in rapturous imitation of her vocal line and even when she opens up it is reflective of the musical demands, perfectly dynamically scaled and never extraneous to it.

Anglo-French mezzo Anna Stéphany is similarly contained but her divisions in her First Act aria Bane of Virtue are finely scaled and precise. If her aria As with Rosy Steps can’t efface memories of Lorraine Hunt Lieberson, that’s hardly her fault, more an index of Hunt Lieberson’s genius; try to hear the Wigmore Hall recording she made with Martin Martineau, which is a distillation of her art, simplicity generating artless serenity and beauty in the truest sense.Stéphany shows proper vocal strength and tonal breath in Defend her, Heav’n. Her Act III Lord to Thee, Each Night and Day – again indelibly associated with Lieberson Hunt – is finely measured and shows Stéphany’s vocal flexibility, her chest voice in the B section, and her fine sense of taste. Not for her DiDonato’s unmusical preening. Septimus is taken by Stuart Jackson and his tart tenor is again part of an ensemble cast devoted to the same musical ends – none of that barking and vocal breaking that you get with the bizarrely over-promoted Michael Spyres, the last person who should be singing Handel – though he can be a touch nasal in From Virtue Springs. The Messenger is from the chorus, tenor Guy Elliott – a very small role but very finely sung.

The chorus offers its own commentaries and is both expertly drilled and takes on a rich sense of characterisation. The chorus that ends Act II, He Saw the Lovely Youth, is taken by Cohen a full minute slower than the rather hustling tempo taken by Maxim Emelyanychev, though in the old Johannes Somary recording it stretches out to a skull-breaking six and a half minutes. Handel was once quoted as saying that this was the greatest chorus he had composed. Somary’s recording, by the way, features some fine singing by such as Maureen Forrester and Heather Harper but it’s heavily cut and can’t be recommended for that reason as well as for the rather inert orchestra responses and consequent lack of style.

The first-class recording confers intimacy but also grandeur at appropriate moments. The booklet has a good number of photographs and a rather too-succinct essay in English, German and French though the libretto is only in English and French.

I realise that recommendations to readers are a question of personal taste and are inevitably provisional; if I like this recording, who’s to say I might not like another new one next month rather more? Assembling a dream team cast for this work is tempting (but futile). Yes, Irene would be Lorraine Hunt Lieberson and Didymus would be David Daniels, half of the Glyndebourne team, and Christopher Purves should have been engaged at some point rather earlier in his career as Valens (he’s recorded the occasional aria on disc). As for the central role, we can argue about it later but it doesn’t help a recommendation now. I cited the McCreesh recording in my last review as a still-recommendable set with the Gabrieli Consort and Players and Gritton, Blaze, Agnew and Bickley in the cast. I’d still be happy with that recording but I suspect that the one under review shows an increased level of psychological insight and ensemble work that makes it my preference.

Jonathan Woolf

Help us financially by purchasing from