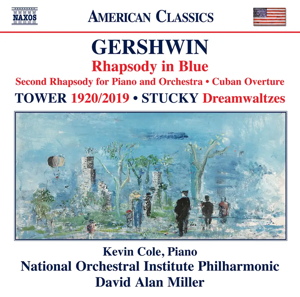

George Gershwin (1898-1937)

Cuban Overture (1932)

Rhapsody In Blue (1924) arr. Ferde Grofé (1892-1972) for piano & orch., pub. 1942

Second Rhapsody for Piano & Orchestra (1931)

Joan Tower (b.1938)

1920/2019 (2019/2020)

Steven Stucky (1949-2016)

Dreamwaltzes (1986)

Kevin Cole (piano), National Orchestral Institute Philharmonic/David Alan Miller

rec. 2023, Elsie & Marvin Dekelboum Concert Hall, The Clarice Smith Performing Arts Center, Maryland, USA

Naxos 8.559934 [72]

The first item here is the catchy Cuban Overture, enlivened by a battery of authentic Cuban percussion instruments and Gershwin’s use of bitonal and even “polytonal” passages. In between the rumba sections is a slow, languorous passage which in part anticipates Porgy and Bess three years later. Many of the Gershwin tropes are apparent and some critics complained that it was “merely old Gershwin in recognizable form” but I would not say it was anything but original and inventive; the end is especially invigorating.

The famous Rhapsody in Blue was originally written for two pianos and has undergone numerous arrangements, including several by the arranger here, Ferde Grofé. This is the “world premiere recording of the Gershwin Critical Edition” of his arrangement for piano and orchestra published five years after the composer’s death, but in addition “[p]ianist Kenneth Cole…has included 44 measures from the original jazz-band version, that were cut for the symphonic iteration” (from the notes). My favourite recording has long been on BMG with pianist Michael Boriskin and the Eos Orchestra conducted by Jonathan Sheffer which also offers the Second Rhapsody for Piano here; there is also a very fine account of just the Rhapsody in Blue as part of a compilation on the short-lived Royal Philharmonic label Tring, with Christopher O’Riley on piano and conductor Barry Wordsworth.

The iconic glissando clarinet opening is played broadly but quite straightforwardly – classically, perhaps, and I prefer a bluesier, loucher (is that a word? It is now) treatment of the kind in the older BMG and Tring recordings but pianist Kevin Cole could not be more alive to the possibilities for variations in colour, subtle rhythmic effects, rubato, accelerando, marcato, sforzando – all the tricks. The luscious “Love” theme beginning at 10:20 is given the full Hollywood treatment; the orchestra makes a lovely noise before Cole plays the decorated and elaborated repeat with the sparkling “cadenza”. The conclusion is fast and furious – very exciting; the whole performance is somewhat hastier than I am used to but it all hangs together, even though the digital sound is a little less sumptuous than that on the RPO recording.

The Second Rhapsody is a different beast; first its syncopated, hammered-out rhythms are suggestive of “the hustle and bustle of the teeming metropolis” (notes) then comes a swooning, lyrical theme, again redolent of the world of romantic, cinematic escapism in which Gershwin was currently working. Kevin Cole is again the essence of virtuosic fluency and conductor David Alan Miller’s direction is sweeping.

After the three Gershwin items come two modern American works. I must say that I would have preferred more Gershwin, especially the Concerto for Piano and Orchestra in F, as Cole was on hand, but I am glad to hear Joan Tower’s piece, as it has an epic, restless, brooding, Lord of the Rings quality which is intriguing. It was apparently written to commemorate the rights and empowerment of women but I listen to it as “pure music” without projecting any concept upon it beyond the general idea of it depicting struggle, rather as much of Shostakovich’s music does, and it is worthy to stand by itself without the need of any subtext. It is tonal, carefully structured and consistently engages the ear. Its conclusion is gentle, questing and enigmatic rather unexpected and very effective.

The premise of Steven Stucky’s Dreamwaltzes is that he nostalgically alludes to waltzes by Brahms and Richard Strauss while acknowledging that the modern composer can write only in a contemporary idiom. I find the prolonged, meandering introduction overlong; it is not until 3:18 that the music hits its stride and takes on some waltzing shape but it soon defaults into a battery quasi-humorous – ironic? – sound effects: trombone slides, little chime bar riffs, twittering flutes and piccolos, xylophone pops and what would once have been called an “Avon calling door chime”. The howling muted horns towards the end are disconcerting and the final two minutes eery and inconclusive. I would much prefer to hear Bernstein’s modern take on the waltz in his Divertimento for Orchestra.

Ralph Moore

Help us financially by purchasing from