Carlos Salzedo (1885-1961)

Trois Morceaux pour Harpe Seule (1910)

Scintillation, for Harp (1936)

Suite of Eight Dances, for Harp (1943)

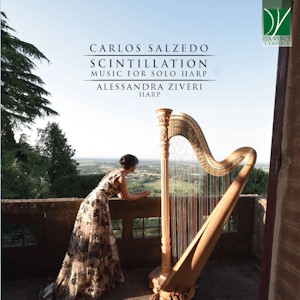

Alessandra Ziveri (harp)

rec. 2021, Palazzo Cigola Martinoni, Cigole, Italy

Da Vinci Classics C00504 [53]

The son of Sephardic Jewish parents, Carlos Salzedo was born, as Charles Moise Léon Salzedo, in the small town of Arcachon, in South-West France, though his parents’ home was in Bayonne. His father Gaston was a singer and teacher of singing, his mother Thérèse a pianist; their son clearly inherited an aptitude for music. Charles Léon was soon learning the piano and, remarkably, his first composition, ‘Moustique’ (Mosquito) was reportedly published when he was only 5. Though that composition is now lost, its main theme is widely thought to be that used in the third (Polka) of the Suite of Eight Dances recorded here. His achievements as a child were such that we might reasonably call him a child prodigy. Certainly, when at the age of 3 he played the piano for Maria Christina, Queen Mother of Spain at her summer-court in Biarritz, she referred to him as “my little Mozart”. There is, I suggest, a kind of symbolic significance in the presence of one of his childhood compositions in a Suite published in 1943, since it has always seemed to me that for all the sophistication of Salzedo’s later achievements as a harpist and a composer for the harp (as, for example, in extended techniques of playing the instrument and innovations in notation and stylistic range) the best of his mature work – such as Scintillation – has at its heart an almost child-like sense of wonder at music and its creation.

Charles-Lèon studied, from the age of six, at the St. Cecilia School of Music in Bordeaux, before the family moved to Paris, when he was nine. He continued with piano and also took up the harp in the capital, initially studying the basics of the instrument with Marguerite Achard (1874-1963). His progress was such that he was accepted at the Conservatoire, where he was taught by Alphonse Hasselmans, before being, at the age of 16 awarded (on the same day) premiers prix for both piano and harp!

Salzedo’s effect on the harp can, I think, be compared to those of Segovia on the guitar and Wanda Landowska on the harpsichord, an effect both of revival and innovation. His work, however, was always grounded in established tradition. So, for example, the Trois Morceaux of 1910 largely occupy a sound-world which would have been familiar to those who knew the music of Debussy and Ravel. Of the three pieces ‘Jeux d’eau’ is the finest, the most adventurous and exciting, its many changes of dynamics and colours beautifully evoking the movements and sounds of water (presumably in a fountain rather than a natural source), rising, falling, splashing and flowing. As a well-trained pianist, Salzedo would undoubtedly have been familiar with works such as Liszt’s Les jeaux d’eau à la Villa d’Este and Ravel’s Jeu d’eau. He was evidently unafraid that those who heard his piece might make comparisons with those works. It will bear such comparisons and implicitly (but perhaps intentionally) makes a case for the harp’s own distinctive range of colours. Alessandra Ziveri presents an intelligent and sensitive reading marked by an impressive sureness of technique. Having said that ‘Jeux d’eau’ is the finest of the Trois Morceaux, I am tempted to qualify or withdraw that statement each time I listen to Ziveri’s interpretation of the last piece in the set, the neo-classical ‘Variations sur un thème dans le style ancien’, a reading full of a happy sense of freedom and lithe agility; perhaps I am being too fanciful, but this sounds to me like music to which Isadora Duncan would have been delighted to dance!

The score of Scintillation is prefaced by the composer’s guidance concerning some of the effects it employs, such as “Gushing chords: Slide briskly from the starting note to the end note, as the arrow points” or “Brassy sounds: Produced by playing with the fingernails very close to the sounding board”. The use of the pedals is also very important in Scintillation, especially in the central glissando which must have suggested the piece’s title, a passage in which it is primarily (and at times only) the changing of pedals which ‘shifts’ the effect of the music. Alessandra Ziveri does something like full justice to the dazzling soundscape the composer encodes in this score; so much so that I would put her performance alongside the best recordings of this piece with which I am familiar, such as those by Judy Loman (Harp Showpieces, Naxos 8.554374) and Yolanda Kondonassis (Scintillation, Telarc 80361).

Ziveri is, unsurprisingly, also an enjoyable guide through the work which closes the programme on this disc – Salzedo’s ‘Suite of Eight Dances’; the eight dances are, in order of performance, a gavotte, a menuet, a polka, a siciliana, a bolero, a seguidilla, a tango and a rumba. As that list illustrates, Salzedo cast his net quite widely in time and place when choosing which dances should make up his suite. His choice reflects, surely not by chance, the trajectory of his life. Salzedo was brought up in Europe and worked there extensively, before in 1909 he joined the orchestra of the Metropolitan Opera, at the invitation of Toscanini. He worked in the USA until he went back to France at the beginning of World War I. He returned to the States in 1916 and lived there for the rest of his life, a busy presence in musical life, as performer, teacher and composer.

The ‘Suite of Eight Dances’ reflects the European and American ‘halves’ of Salzedo’s life. The first four dances in the Suite are essentially European, while the second four are more ‘exotic’ (and predominantly ‘American’ in origin. The first four dances – gavotte, menuet, polka and siciliana are long-established dances often encountered across the history of classical music, while the second four – bolero, seguidilla, tango and rumba – were, for the most part, still relatively unfamiliar in the classical repertoire when this work was written in 1943 (a work such as Ravel’s Bolero being an uncommon exception). Of the second group of four dances, the bolero and the rumba seem to have originated in Cuba, while the tango mainly grew up in the port cities of Argentina, often being danced in the brothels and bars of those cities in the late 1900s. Although the seguidilla may well have originated in Castile, its most commonly heard form seems to have developed in Andalusia, influenced by the music of the moors and the gypsies and perhaps the Sephardic Jewish population too.

Alessandra Ziveri plays all eight dances with lucid clarity and sensitive judgement of tempi. Particular highlights include the Bolero and the Tango. In the first of these the changing dynamics are well handled, not least in the conclusion of the piece, with its surprising drop in volume and its closing pianissimo. The Tango’s slow and sultry theme is heard over a steady accompaniment. Ziveri handles the relationship between theme and accompaniment very persuasively.

When I consulted her website, I learned that Ziveri, who was originally from Parma, studied at the Conservatorio di Musica Giuseppe Nicolini in Piacenza and the Conservatorio di Musica Arrigo Boito in the city of her birth, and that she released three CDs with Tactus between 2013 and 2017. Unfortunately, I haven’t heard any of these earlier CDs, but my pleasure in her work on the disc under review will certainly prompt me to try to put that right.

Glyn Pursglove

Availability: Da Vinci