Maurice Ravel (1875-1937)

Complete Solo Piano Music Volume 3

Valses nobles et sentimentales (1911)

Le Tombeau de Couperin (1917)

A la manière de Chabrier (1913)

A la manière de Borodine (1913)

La Valse (1920)

Prélude (1913)

Fugue in B flat major

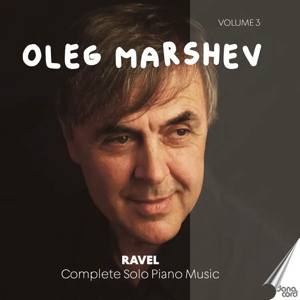

Oleg Marshev (piano)

rec. 2023, Cultural Institute, Milan, Italy

Danacord DACOCD905 [75]

This issue presumably completes Oleg Marshev’s intégrale of Ravel’s piano music. The last item here is an unpublished Fugue in B flat. The booklet notes are silent about it, as is Roger Nichols’s 2011 book on Ravel in the Master Musicians series, and Paul Roberts’s 2012 Reflections: The Piano Music of Maurice Ravel. Equally obscure fugues appear in Marshev’s previous volumes. They may have been composed for the annual competitions for the Prix de Rome, a lucrative and prestigious prize that eluded Ravel. Entry required a preliminary examination each May, and that included writing a four-part fugue. These pieces aid the claims to completeness beyond what the many two-disc compilations of Ravel’s published solo works routinely claim. This Fugue is by no means negligible, even if its agreeably fluent counterpoint does not sound especially characteristic of its composer.

For most collectors, the main appeal of the disc should lie in the two major items which take up two-thirds of the duration: Valses nobles et sentimentales and Le Tombeau de Couperin. Along with Gaspard de la Nuit (volume 2) and Miroirs (volume 1), they are at the core of Ravel’s achievement for solo piano. Alas, neither work is a great success here.

The first of the Valses nobles et sentimentales revels in the acerbic harmony well enough, but the feeling of the waltz is rather too sturdy, with a timing of 1:39 against the usual 1:10 to 1:20. But the real problems lie in the slower numbers, beginning with the second, marked Assez lent – avec une expression intense. Its metronome mark is not that slow. Ravel spoke to Henriette Faure, a young pianist whom he coached in this work, of “shades of rubato, very slight, very slight, and quickly suppressed by Ravelian vigilance”. He was a known stickler over tempo and ‘expressive’ exaggeration; he marked Vlado Perlemuter’s score Simple at one point. Marshev plays the piece much too slowly, and his hesitations distort the music’s flow to a degree that renders the pulse inaudible and the music becalmed. The timing range is quite narrow across complete recordings: Stephen Osborne 1:14, Pascal Rogé 1:17, Arthur Pizarro 1:18, and Jean-Efflam Bavouzet 1:21. Marshev takes 3:25!

Modéré,the third waltz usually played between 1:12 and 1:31, requires 2:00 in Marshev’s hands. He stretches to 2:13 the fifth waltz Presque lent, where the norm is 1:19-1:35. These timing differences in short pieces are not just a matter of tempi. Excessive rubato steals the music’s intended dance-like flow. The difficult Épilogue lent is more successful. Marshev only odds one-fifth to the usual duration, and renders this closing scene as a poignant envoi.

Le Tombeau de Couperin,usually about 23 minutes, takes 30:12 here. We have some of the same problems, if nothing quite as distorted as the second of the Valses nobles et sentimentales. But the Forlane’s 8:41 (versus the typical 5:50-6:50) almost makes that lovely piece outstay its welcome. At least, the final Toccata is a tour-de-force of brilliant playing at its normal fast tempo.

The Borodin and Chabrier pastiches are played well, if more slowly than any versions I know. La Valse is not always included in the complete set, because the solo piano version was for ballet rehearsal purposes. It is not sufficiently developed for concert performance. Stephen Osborne includes it, and adjusts parts when needed. His fine performance lasts 11:40. Marshev gives a decent account at 12:51.

If you seek the two main suites, Valses nobles et sentimentales and Le Tombeau de Couperin, look elsewhere, especially if you are new to the works. You will find superior, and certainly more central, accounts on any of the two-CD cycles mentioned above.

In fairness, I should note that I appreciate Oleg Marshev’s Rachmaninov and Brahms recordings for Danacord. Others have praised the first two discs of the Ravel cycle, certainly welcomed on this site (review ~ review).

Roy Westbrook

Previous review: John France (January 2023)

Help us financially by purchasing from