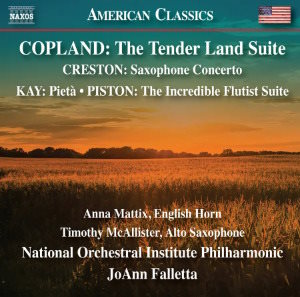

Aaron Copland (1900-1990)

The Tender Land Suite (1958)

Paul Creston (1906-1985)

Saxophone Concerto, Op 26 (1941)

Ulysses Kay (1917-1995)

Pietà (1950)

Walter Piston (1894-1976)

The Incredible Flutist Suite (1940)

Anna Mattix (English horn), Timothy McAllister (alto saxophone)

National Orchestral Institute Philharmonic/JoAnn Falletta

rec. 2022, Elsie and Marvin Dekelboum Concert Hall, The Clarice Smith Performing Arts Center, College Park, USA

Reviewed as a digital download from a press preview

Naxos 8.559911 [65]

The National Orchestral Institute is a month-long program for outstanding conservatory students held annually at the University of Maryland just outside of Washington, D.C. This varied and well-designed program, the sixth in a series of recordings of the Institute’s ensemble released on Naxos, is under the direction of the always interesting JoAnn Falletta. The four mid-20th-century American composers featured here all favored traditional forms and styles, and only one of these works, the Suite from The Incredible Flutist, can be said to be really familiar.

Several of the discs in the Naxos series have received considerable critical acclaim. I recommend in particular the Ruggles/Stucky/Harbison (Naxos 8.559836, review and review) and the Gershwin/Harbison/Tower/Piston discs (Naxos 8.559875, review and review). On the evidence of the recordings, these talented young musicians, a different group every year, blend together very quickly into an ensemble of extraordinary refinement and precision. And while this new recording is not the most interesting of the bunch, there is certainly a great deal to enjoy.

The orchestral suite crafted by Aaron Copland in the late 1950s from his opera The Tender Land has received surprisingly few recordings over the years. If not exactly top-drawer Copland, the suite is a lovely work that grows on me with each hearing. Lyrical sections frame an energetic middle section drawn from the dance music of Act 2 of the opera. The opening section features music from the beginning of Act 3 followed by the love music from Act 1, while the expansive final section is an elegant arrangement of the quintet ‘The Promise of Living’ that closes Act 1.

Copland’s own recording, made with the Boston Symphony in 1959 not long after he reworked these portions of the opera into the suite, has never, as far as I know, been out of print. His performance balances the lyrical and energetic beautifully, and the RCA Living Stereo recording still sounds terrific. No doubt the authority of Copland’s interpretation explains the relative paucity of more recent recordings. Thus Falletta’s new version, offering a somewhat softer edge than Copland’s own version, is welcome and rises to the top of the list of alternative versions. If the party music occasionally loses momentum, there is a compensatory breadth and grandeur, especially in the final pages of ‘The Promise of Living’ music.

The second and third works on this disc are, more or less, premiere recordings. Paul Creston’s Concerto for Alto Saxophone, written in 1941, was championed early on by Vincent J. Abato, who gave the first performance in January 1944 with the Philharmonic-Symphony Orchestra of New York and William Steinberg (substituting for an ailing Artur Rodzinski). A high-spirited 1945 broadcast performance by Abato, with Stokowski and the Hollywood Bowl Symphony Orchestra, was issued on Guild GHCD 2424 (review and review). There have been, in addition, a couple of recordings of the concerto in arrangements for concert band, but this new recording, with the suave Timothy McAllister as soloist, is the first studio recording in the Concerto’s original orchestral guise.

In the 1940s and 50s Creston was quite a prominent composer, with a most distinctive stylistic voice. By the mid-1960s, however, his music had fallen into neglect, especially his works in the more ambitious genres, though in recent years there are signs of increasing interest. Creston’s music always conveys an appealing rhythmic vitality (Creston wrote a treatise on the topic called Principles of Rhythm in 1964) coupled with an accessible yet rich harmonic language. The Concerto is typical of his virtuosic works, energetic and rather conventional, but in the hands of a skilled soloist and disciplined ensemble, it is an effective piece. The opening movement is the weakest, I think; the main thematic material is not particularly interesting, nor is the working-out of that material. The emotional core is the lyrical slow movement, marked ‘Meditative’. McAllister and Falletta take a somewhat reserved approach that fits the spirit of the music nicely and perfectly sets up the delightful rhythmic play of the finale. Once again the Institute orchestra acquits itself very well throughout. Falletta has them playing with precision and verve. The textures are clear, and the recorded balance between soloist and orchestra is ideal.

Ulysses Kay is another neglected composer whose music deserves much greater recognition. He was most productive in the 1950s and 60s, and remained active into the 1980s, working in all major genres. A number of his orchestral compositions are decidedly impressive. Kay favored a concentrated, lyrical melodic style and a rich harmonic palette, and he had an imaginative ear for texture and orchestral color.

Kay’s Pietà is a modest work, a lovely and haunting meditation for English horn and strings, performed here by Anna Mattix. Kay was clearly fond of the sound of the oboe, and wrote several works for that instrument before composing Pietà in 1950, while he was in Rome in 1950 after winning the Prix de Rome. Mattix, a member of the Buffalo Philharmonic Orchestra, performed it with Falletta and that ensemble in March of 2021, a live performance that was issued on the BPO’s in-house label (‘Light in a Time of Darkness’, Beau Fleuve 605996-998579). The performance on this disc marks its first studio recording. (Disclosure: Anna Mattix and I were faculty colleagues at DePauw University some years ago.) Mattix plays beautifully and expressively; I marginally prefer the live Buffalo performance for its added intensity and richer string. But the differences are of no import, and you will be happy to make the acquaintance of Pietà in either performance.

The final work on this disc is the most familiar and makes for a delightful conclusion: Walter Piston’s tuneful, entertaining suite from ballet The Incredible Flutist, written in 1938. Piston was a much-admired craftsman, master of all elements of the compositional arts, and one of the most gifted of the mid-century American symphonists. Every time I encounter The Incredible Flutist, I find myself wishing Piston had indulged more often in this more theatrical side of his personality; the work overflows with delicious verve and color.

The Incredible Flutist has been very lucky on recordings. (There is no reason why it should have been the property, almost exclusively, of American orchestras.) Arthur Fiedler and the Boston Pops made the first recording in 1939, followed by a second one in 1953. Howard Hanson and the Eastman-Rochester Orchestra in 1958 and Leonard Bernstein and the New York Philharmonic in 1963 made terrific recordings. Leonard Slatkin with St. Louis, Gerard Schwarz with Seattle, and Andrew Litton with Dallas all recorded successful performances in the early 1990s, give or take. Most recently, the live performance by Carlos Kalmar and the Oregon Symphony (2013-14) was well-received (review). Of all these, the Bernstein stands out for its inimitable élan and dash.

Falletta’s new recording can take its place in this distinguished company. Tempi are well-judged, and the orchestra once again plays up to its high standards. Perhaps compared to the best of the above, the result is somewhat faceless, although the wonderful Tango has a graceful lilt. The Circus March is strait-laced but the Spanish Waltz has terrific energy. The young flute soloist is rather self-effacing compared to the most successful of eponymous Flutists. In any event, one will certainly not be unhappy with this performance. (But be sure to listen to Bernstein sometime!)

All in all, this is an enjoyable, well-designed program, superbly played by a young ensemble under the accomplished hand of a stylish conductor, another addition to a splendid series, complete with two studio premiere performances. Intelligent booklet notes by Frank K. DeWald.

Jeffrey Hollander

Previous review: John France (January 2024)

Help us financially by purchasing from