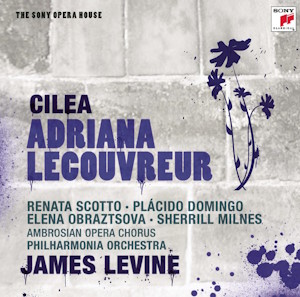

Francesco Cilea (1866-1950)

Adriana Lecouvreur (1902)

Renata Scotto (soprano) – Adriana Lecouvreur

Plácido Domingo (tenor) – Maurizio

Elena Obraztsova (mezzo) – La principessa di Bouillon

Sherril Milnes (baritone) – Michonnet

Ambrosian Opera Chorus

Philharmonia Orchestra/Renato Palumbo

rec. 1977, Studio No 1, Abbey Road, London

Sony 88697446212 [2 CDs: 134]

This 47 year old recording still has merit as one of the best audio representations of Cilea’s most famous opera. With the recent passing of legendary diva Renata Scotto, I thought it was worth taking a look at this old recording again. Currently it is only available as a digital download in the Sony Opera House Collection, but at the current prices (January 2024) one can purchase it for less than $10, which makes it a very budget conscious choice to purchase.

The French stage actress Adrienne Lecouvreur (1692-1730), who was one of the stars of the Comédie-Française is now only remembered because of Cilea’s opera, and to a lesser degree, the play that it was based on, by Ernest Legouvé and Eugène Scribe. The play was one of the famous vehicles to display the talents of Sarah Bernhardt in which she undoubtedly extracted every ounce of melodrama for her audiences. It is a singularly ironic fact that Lecouvreur’s name is tied to an opera in which the heroine is supposed to act out a scene from Racine’s Phèdre; because it is usually performed so histrionically as would be likely to cause Mme Lecouvreur to turn sommersaults in her grave. While far from being considered the best actress of her time, Lecouvreur was highly regarded as the first thespian in France to make declamatory speech more natural and closer to a conversational manner than what had been on display in French theater up to that point. The fact that Racine’s monologue is often so poorly delivered is not entirely the fault of the sopranos who portray her; that blame rests squarely on Cilea’s shoulders, as his busy score serves to underline every melodramatic device from the original play.

The main reason for the existence of this recording was the mid-1970s growing celebrity of Renata Scotto as primma donna assoluta, especially in the United States where she concentrated much of her career at that time. She added the role of Adriana Lecouvreur to her repertoire in the same year that this recording was made. Scotto has the full temperament to take on this role successfully; something which cannot be said of either Renata Tebaldi or Joan Sutherland on rival recordings. Vocally she tends to draw out her lines for expressive effect though her tone will suddenly splay out at fortes above the staff. Even this handicap she uses to good dramatic effect which helps her characterization. Her two main arias, particularly “Poveri fiori”, are absolute lessons in masterly bel canto vocal technique of maintaining long phrases and control of the vocal line. The Phèdre recitation is especially vivid as she seems to be aiming to recreate the kind of declamation that Lecouvreur was noted for, at least as much as Cilea’s music will allow her to do that.

Plácido Domingo is a deluxe Maurizio singing ardently and with a full range of dynamics on display. Likely, working with Scotto encouraged him to produce a more sensitive Conte de Saxe than the majority of tenors aim for. His vocal acting is a bit generalized, but he tries to invest more expression into his big tune, “La dolcissima effigie” than any other tenor that I have encountered. In addition, he is really sensitive in his phrasing of “l’anima ho stanca” in the Second Act.

Elena Obraztsova has a huge, rich-toned voice with an impressive ability to project. That is the Achilles heel of her portrayal of the Princesse de Bouillon; in her major scenes she always seems to be aiming to thrill the folks sitting in the back rows of the topmost balcony. Curiously she does manage to reduce her tone more sensitively in some of the recitative sections of the score. Still, if one isn’t looking for a more bel canto approach then they may just sit back and revel in her prodigious tone, particularly her rich, full lower register.

Sherril Milnes’ incisive baritone is more naturally suited to depict villains than it is to the sentimental, fatherly theater director, Michonnet. He modulates his tone to produce a sympathetic, but not cloying portrayal of a man whose hopes for love are doomed to disappointment

Smaller roles which stand out here are Florindo Andreolli’s rich portrait of the Abbé de Chazeuil,who fawns over the ill-matched royal couple (sound familiar?). Giancarlo Luccardi registers a dignified and smoothly vocalized portrayal of the Prince de Bouillon.

James Levine clearly loves this score as he invests it with so much more careful attention than it often receives. His tempi are never rushed, even in the frequently bustling music that accompanies the backstage activities that are represented onstage. The ballet is meant to be a showpiece and is tackled with real aplomb. The Philharmonia Orchestra gives a very professional account of the score; the brass sections, especially the trumpets, were in fine form during these sessions. The recording engineers provided sound that is typical of its time, relatively close in perspective for the voices and slightly more distant for the orchestra. It has been nicely refurbished for the digital era. This recording is a fine representation of a very effective opera that doesn’t often receive the kind of consideration that it did during these recording sessions.

Mike Parr

This was the recommended stereo version in Ralph Moore’s survey of the opera.

Help us financially by purchasing from

Other cast members

Florindo Andreolli (tenor) – Abate di Chazeuil; Lilian Watson (soprano) – Jouvenot; Ann Murray (mezzo) – Dangeville; Paul Crook (tenor) – Poisson/ Un maggiordomo; Paul Hudson (bass) – Quinault