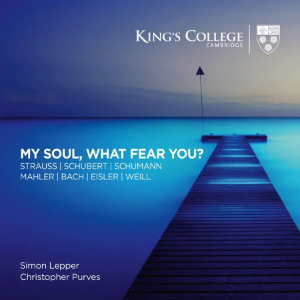

My Soul, What Fear you?

Christopher Purves (bass-baritone)

Simon Lepper (piano)

Miloš Milivojević (accordion); Sarah Field (saxophone); Lucy Shaw (double bass); Lily Vernon-Purves (flute); Rafael Onyett (guitar)

rec. 2022, St John the Evangelist Church, Oxford, UK

Texts & English translations included

King’s College, Cambridge KGS0067 [56]

Many singers who have sung as Choral Scholars in the Choir of King’s College, Cambridge have gone on to have distinguished careers as solo artists. A few years ago, someone had the inspired idea to get no less than ten former Choral Scholars to record an album of songs by British composers under the title Proud Songsters (review). Their accompanist was another alumnus of the College, Simon Lepper. One illustrious name missing from the roster of artists who recorded Proud Songsters was that of Christopher Purves. Instead, he has now set down a full album for the King’s College label and once again Simon Lepper has been recruited as pianist.

I was very surprised to learn that this is Purves’ first solo album of song. It’s clear that he’s taken great care over the construction of the programme, in which endeavour he has been helped by the Lieder expert, Richard Stokes, who has written the notes for the booklet. The fons et origo of the programme was Weill’s Das Berliner Requiem and specifically the aria ‘Alles, Was Ich euch sagte’, a piece to which Purves is strongly attached. He had performed the complete work with Gerard McBurney and subsequently discussed with him the possibility of making a new arrangement of the aria in question, using reduced instrumental forces. Another composer, Bertie Bagent was soon enrolled in the enterprise and arrangements of the Bach aria and three songs from Eisler’s Hollywood Songbook were added to the mix. The three arrangements involve all six of the instrumentalists; Simon Lepper is a constant presence throughout the programme.

When we open the booklet, we find that the title, ‘My Soul, What Fear you?’ is followed by a sub title, ‘Songs of War and Refuge’.

Purves opens with a group of three Strauss Lieder. All three are well suited to his voice; he and Lepper do them very well. In Im Spätboot the singer is required to go down to a bottom D on the very last word; Purves manages that with seeming ease. Nachtgang is interesting in that it’s a setting of a prose poem. I like the way that Purves conveys the sense of rapture in the second half of the song.

I’d never heard Pfitzner’s Hussens Kerker (Hus’s dungeon) before and I suspect it’s something of a rarity. The poem imagines the thoughts of the Czech reformer Jan Hus (c 1372-1415) as he awaits execution for heresy. As you’d expect, Pfitzner’s setting is serious and intense and it seems to me that Purves is an ideal choice to sing this song. The piano part is strongly atmospheric and Lepper plays it expertly.

I admit I approached the arrangement of Bach’s celebrated aria with a little trepidation since I love this sublime aria in its original form. So far as I can tell, the wonderful instrumental obbligato is largely, if not entirely, played by the alto saxophone with the flute given the violin line (I may be wrong about this). Purists may object, but I was won over, not least because it seems to me that Bertie Bagent’s instrumentation is faithful to the spirit of Bach’s music. Furthermore, the timbre of the alto saxophone, eloquently played by Sarah Field, is a convincing foil to Purves’ singing.

A group of Lieder by Schubert follows. Der Sieg is a setting of a poem by the composer’s friend Johan Mayrhofer (1797-1836). Richard Stokes reminds us that this poet took his own life and also made an unsuccessful attempt to do so in 1831. This particular poem, says Stokes, “makes veiled and prophetic reference” to his suicide. It seems to me that Schubert’s music has the air of elevated melancholy. Purves sings the song very well. Grenzen der Menschheit is a Goethe setting. It’s a big, searching song, as befits Goethe’s text, and Purves’ delivery of it is imposing. In between comes Totengräberlied, the song of a gravedigger. Given his occupation you might expect a serious poem (by Hölty) allied to serious music. However, this gravedigger is a cheery chap and Purves sings the song with appropriate relish. This is an intelligent bit of programming because the song offers good contrast with the two items that surround it.

Schumann comes next. I especially admired in Der Schatzgräber the way in which Purves and Lepper put over the frenzy with which the treasure-seeker digs in his quest for buried treasure.

Bertie Bagent’s arrangements of three numbers from Eisler’s Hollywood Songbook seem to me to be entirely successful. In ‘L’Automne californien’ (which is in German, despite its French title) the ensemble adds very effective touches of colour to Eisler’s music. The accompaniment to the Brecht setting, ‘An den kleinen Radioapparat’ is very delicate, partnering Purves’ delightfully light singing. (Is Brecht the only poet who has written a poem ‘to a portable radio’? I suspect he is.) Last comes ‘An eine Stadt (Franz Schubert gewidmet)’. In Hölderlein’s poem, here adapted and shortened, the city in question is Heidelberg. Richard Stokes expresses the view that “Eisler’s music mirrors the poet’s nostalgia without ever spilling over into sentimentality”. I agree and would add that in this arrangement the different timbres of the instrumental group reinforce Eisler’s music in ways that seem entirely apt.

Der Tamboursg’sell is one of Mahler’s greatest, most eloquent songs. Purves is intense and dramatic in his delivery and he’s perfectly supported by Lepper. In particular, I was impressed by the way in which Lepper prepares us to hear the final stanza of the poem (‘Gute Nacht, ihr Marmelstein’). That last stanza is then performed with great sadness. A marvellous performance by both artists.

Finally, Purves sings the Weill aria that prompted the programme. Unsurprisingly, he sings it with much feeling. Gerard McBurney’s arrangement is convincingly idiomatic. The use of the accordion gives the music a real whiff of the era of the Weimar republic, as does the saxophone, when it is brought into play later on in the piece.

This is a fascinating Lieder recital. The programme has been curated with perception and intelligence and it works very well. The standard of performance from all the instrumentalists is consistently high and I found Christpher Purves an expert and illuminating interpreter of the music; I hope he’ll be inspired to do more recitals on disc. Producer Benjamin Sheen and engineer Dave Rowell have done a fine job as far as the recorded sound is concerned. The booklet is excellent; Richard Stokes’ essay about the music is illuminating.

John Quinn

Help us financially by purchasing from

Contents

Richard Strauss

Gefunden (6 Lieder, Op. 56, No. 1)

Nachtgang (3 Lieder, Op. 29, No. 3)

Im Spätboot (6 Lieder, Op. 56, No. 3)

Hans Pfitzner

Hussens Kerker (4 Lieder, Op. 32, No. 1) |

Johann Sebastian Bach (orch. Bertie Bagent)

Ich habe genug, BWV 82: I. Aria: Ich habe genug

Franz Schubert

Der Sieg, D 805

Totengräberlied, D 44

Grenzen der Menschheit D 716

Robert Schumann

Der Schatzgräber (Romanzen und Balladen, Vol. 1, Op. 45, No. 1)

Frühlingsfahrt Op. 45, No. 2

Hanns Eisler (orch. Bertie Bagent)

The Hollywood Songbook: No. 21, L’Automne californien |

The Hollywood Songbook: No. 3, An den kleinen Radioapparat

The Hollywood Songbook: No. 24, Hölderlin-Fragmente, V. An eine Stadt (Franz Schubert gewidmet)

Gustav Mahler

Des Knaben Wunderhorn: XII. Der Tamboursg’sell

Kurt Weill (orch. Gerard McBurney)

Das Berliner Requiem: V. Alles, Was Ich euch sagte