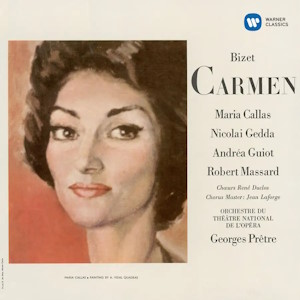

Georges Bizet (1838-1875)

Carmen (1875)

Maria Callas – Carmen (soprano)

Nicolai Gedda – Don José (tenor)

Andréa Guiot – Micaëla (soprano)

Robert Massard – Escamillo (baritone)

Claude Cales – Moralès (baritone)

Jacques Mars – Zuniga (bass)

Choeurs René Duclos, Choeurs d’enfants Jean Pesenaud,

Orchestre du Théâtre National de l’Opéra Paris/Georges Prêtre

rec. 1964, Salle Wagram, Paris, France

Reviewed as download in FLAC format

Warner Classics 2564634110 [146]

CALLAS IS CARMEN, or so the advertisements claimed in 1965 when this recording first hit the market. For decades opera lovers have been debating the relative merits of Leontyne Price, Marilyn Horne, Teresa Berganza, Victoria de los Ángeles, Tatiana Troyanos and others as to who embodies the most perfect Carmen on disc. There is one significant reason to include Callas’ Carmen in one’s collection, other than the diva herself; that is that it is the most perfectly Gallic recording of the opera from the stereo era. Despite the fact that two of the principals here were not born in France, every other recording of this opera in some way dilutes the utter Frenchness (to coin a word), of Bizet’s masterpiece no matter what other merits they possess. Other polynational casts are missing that most essential quality of Bizet’s masterpiece that is on display here.

When it comes to Callas her French diction is astounding, both sung and spoken, for one who was not born in France. Paris was her home for many years and she came to speak French like a native-born Parisienne. Vocally Callas was in good vocal state when these sessions were made; rarely does a top note go awry. As always with Callas she invests a great deal of herself in attempting to illuminate the character with little vocal nuances that no other singer has ever tried to do in such an extreme fashion. Callas presents a vividly playful Carmen in the earlier acts. One can hear just how she invests a unique shading to the key line of the Habanera, “Et c’est l’autre que je préfère”. When she sings “Prends garde à toi” this Carmen really means it. In the Séguedille, Callas does not attempt to seduce in the first verse; instead she makes an intensely personal statement which only becomes more kittenish after José’s response. Surprisingly, Callas does not overuse her chest voice in the role; she almost always tends to employ other means to illustrate the character. For example, in the Chanson Bohémienne she uses her most covered-sounding tone to convey Carmen’s Gypsy mystique, and the captivating way she uses portamenti in the taunting of Zuniga during “Bel officier”. In “au quartier, pour l’appel” she actually employs rubato in her shaping of the phrases while she mocks José; this is something that has become virtually a lost art and only the most skilled of singers have the ability to use it. Callas saves all of her fire, (and darkest chest tones) for the final duet. Some people have described Callas’ Carmen as “nasty” or “bitchy” which is probably comes from this one highlight of the opera. If one wonders where Callas found the fire and temperament that she displays here, one has only to look at the famous photo of her being served with a court summons after her final performance in Madama Butterfly in Chicago in 1958. Callas herself said of Carmen “Colour is everything, and violent colours are an integral part of Carmen. But it must not be vulgar.”

Nicolai Gedda’s Don José was already a known asset from his recording for Thomas Beecham of five years earlier (review). Gedda’s fluency in languages other than his native Swedish, particularly French, was world renowned; the perfection of his sung French is well-displayed on this set, particularly in the recitatives where tonal production is a lesser consideration. His voice had expanded a little in size since the earlier recording and here he projects his top voice brilliantly; he does greater justice to José’s darker side. He turns the Flower Song into a love letter to Carmen, even inserting little hints of desperation into his vocal line. The climactic B flat is sung in a true French-sounding voix mixte (blending the head and chest voices together). Perhaps the B Flat was sung with slightly more freedom on the Beecham recording, but only by a hair’s width. It takes a very bold tenor to pair up against the riveting Carmen of Callas. Gedda allows Callas the limelight during the first two acts but once José’s jealous nature and desperation show themselves, he assumes full command of his stage presence to match Callas at every point.

Andréa Guiot’s Micaëla has the slightly astringent sound that one customarily hears from French sopranos. Her sound is basically sweet and when she sings out in full voice her upper range reveals an amplitude that suggests that she was ready to move on to heavier roles when this was recorded. Her performance of the Third Act aria leaves one with the impression that this is a very courageous girl, even if she doesn’t quite steal the heart of the listener as Mirella Freni did in her three complete recordings.

Robert Massard is a fine Escamillo, one who copes better with the low notes of the Toreador song than most baritones do. His most extraordinary feat is that he actually manages to add nuance and shading to that aria, which is usually presented as a feast of extrovert machismo. Massard demonstrates that it has the potential to be more than that.

The excellent supporting cast is made up from the finest regional French singers of the day. Claude Cales’ Moralès starts the opera off with his very forwardly placed tone, and defines the epitome of French style, where the pronunciation of the word comes slightly ahead of tonal production. He even endows Moralès with a degree of irresistible charm, with which to tempt Micaëla. Nadine Sautereau makes a welcome flirt as Frasquita, and the very young Jane Berbié gives the very first of her three complete accounts of Mercédès (she was also the choice of Solti and von Karajan for their recordings). There is one oddity in the casting of Remendado, who is sung with deliciously suspect character by Jacques Pruvost. However, for two of the tracks in Act Two he is taken by another singer, Maurice Maievski, presumably because of illness or other unfortunate circumstances.

Overseeing the entire enterprise is the sure guiding hand of Georges Prêtre. He completely reconceived the musical traditions that had accrued around Carmen performances in France. He rejected those which he felt had no dramatic reasoning. This is a very swift Carmen, generally speaking. Prêtre refuses to linger over the languorous delights of the smoking chorus (as so many other conductors do). This makes perfect dramatic sense when you consider that the factory workers are only released for a short smoking break. He regularly takes the opera back to its roots in the traditions of the Opéra Comique in such numbers as the Quintet or the Smugglers’ Chorus of Act Three. He brings out the ironic mocking personality of the Act Two Prelude. No-one could accuse him of over-pointing the music as Leonard Bernstein does, or of drawing out the music to Wagnerian proportions as Herbert von Karajan does on his two recordings. One only has to listen to the fast, fiery clip at which he paces the Chanson Bohémienne to conclude that his decisions are dramatically correct each time. He is working with orchestra of the Paris Opera here, who had long been known for being less than perfect in their ensemble. Here they sound as if they have been rehearsed within an inch of their lives. Their playing still had the characteristic sound of a French orchestra, now lost today; it is particularly noticeable in the playing of the French horns. There were only a small number of times that their precision was less than ideal. The Paris Opera Chorus had an even worse reputation at the time than the orchestra did, so EMI hired the René Duclos chorus who are generally superb. It is such a pleasure to hear a chorus whose French diction is so immaculate that one can make out every word without reading a libretto. Sampling the fight among the factory women illustrates this point perfectly, as it is all remarkably clear.

I auditioned this recording in the high resolution FLAC version (96 khz/24 kbps). When heard using the correct equipment to handle the higher sampling rates, the expanded sound tends to reveal more in the orchestral detail than it does with the voices. In this case, violins sound sounds more like they do in a live performance whereas on recordings they often seem to acquire an extra sheen one doesn’t notice in person. Woodwind textures are less homogenous and also sound more realistic, but the sound of cymbals can come across as more edgy and aggressive. This download contains a digital booklet but with no libretto.

While this recording stands out as the most authentically French version of the stereo era, there are two recordings that come near to its achievement and only lose out by a fraction. The 1959 EMI recording under Thomas Beecham has excellent French credentials; although Victoria de los Ángeles’ Carmen possesses greater charm than Callas’, however; her French diction does not quite stand up to the standard set by Callas. A later recording on Erato with Régine Crespin, under Alain Lombard, has a more French cast than this one but it is less-well performed all-around than Prêtre’s, and it has been unobtainable for ages. The only real French competition to this recording lies in a handful of recordings from the mono era, but that is an entirely other story. No matter which is your preferred Carmen recording from the stereo era, this one is worthy to include alongside it for you to be able to experience the opera in something close to French perfection.

Mike Parr

Help us financially by purchasing from

Other cast members:

Nadine Sautereau – Frasquita (soprano)

Jane Berbié – Mercédès (mezzo)

Jean-Paul Vauquelin – Le Dancaïre (baritone)

Jacques Pruvost/ Maurice Maievski – Le Remendado