Ilmari Hannikainen (1892-1955)

Variations fantasques, Op 19 (1923)

Trois valses mignonnes, Op 17 (pub.1921)

Aarre Merikanto (1893-1958)

Sechs Klavierstücke, Op 20 (1919)

Jean Sibelius (1865-1957)

Three Sonatines, Op 67 (1912)

Finlandia, Op 26 (pub.1905)

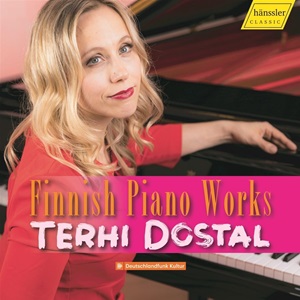

Terhi Dostal (piano)

rec. 2022, RBB Saal 3, Berlin

Hänssler Classic HC23048 [74]

I will admit that once upon a time I would have been hard-pressed to name a Finnish composer other than Sibelius; thankfully, that was a long time ago. An early encounter with Selim Palmgren’s gorgeous second piano concerto set me straight and began to make me aware of a whole world of Finnish piano, though I still have many more gaps than I do music. Ilmari Hannikainen is one name that I am glad to have made the acquaintance of; his piano concerto can be heard on YouTube and Risto-Matti Marin’s ALBA disc Romantic Finnish Piano Music (ABCD446 review) gave us his early and wonderfully romantic Piano Sonata in C minor. Terhi Dostal introduces us to a major large scale work, the Variations fantasques alongside three waltzes from the same period. She couples these with the Sechs Klavierstücke, Op 20 by Aarre Merikanto, an almost exact contemporary of Hannikainen, and works by Jean Sibelius.

Ilmari Hannikainen was born into a musical family and would have been surrounded by music from an early age; the local chamber society were regulars at his family home, rehearsing and performing and several musicians emerged from this culturally rich environment; brother Tauno was a conductor, Arvo was a violinist, Väinö a harpist and Ilmari himself who was a distinguished pianist as well as composer; one of his teachers was Liszt pupil Alexander Siloti, who also taught Rachmaninov and noted Russian pianists Alexander Goldenweiser and Konstantin Igumnov. Hannikainen often performed in the UK and gave the UK premiere of Rachmaninov’s First Piano Concerto. His Variations fantasques were written in a difficult time following the death of his brother Lauri; he died in a drowning accident, as Hannikainen himself did in 1955. One cannot say how this affected his writing, though the theme is certainly sombre with wonderfully evocative bell like tones. There is a vast range of mood and texture within the 19 variations. Though there are moments that hint at Schumann – the dotted rhythms of variation ten or the finale – the harmony is predominantly late romantic chromaticism with hints of impressionism. With a healthy amount of virtuosity in many variations such as the toccata-like sixth, the quicksilver twelfth or the athletic jumps of the thirteenth that reminded me of York Bowen, it is the more unusual variations that hold much of the interest. The second creates a shimmering sound with fast repeated notes surrounding the unison theme, while variation four features tiptoeing chords interrupted by a constant triplet trumpet-call. An unworldly waltz follows, a foil to the more salon-like waltz of variation nine and variation eight alternates legato and almost oriental staccato phrases. An obsessive semitone figure rides over tolling bass notes in variation seventeen and leads to a variation that is something of a cadenza-come-fantasy in imitation of a piper’s free improvisation before the energetic finale takes over. This is a startlingly original piece, though I admit it took me a few listens before I fully realised this. The charms of the three valses mignonnes are more immediate and their mix of luxuriant romanticism and Chopin-like elegance makes one wonder how Hannikainen has remained in the shadows outside his native country.

Aarre Merikanto was the son of composer Oskar Merikanto and like Hannikainen he taught at the Sibelius Academy; his pupils included Einojuhani Rautavaara. His impressionist credentials are clear from the very opening of the first of his six piano pieces Melodie, where the spirit of Debussy’s Sunken Cathedral hovers. The melody itself is delicate, singing over a flowing left hand. Pan, a depiction of the frivolous and wild Arcadian God is a skittish scherzo, part frolicsome, part rustic flute melody, is followed by Improvisation whose arpeggios create a swirling and surging accompaniment to the left-hand melody. The fourth piece, A dream, shares some of the mood of the opening piece and the fifth, Scherzo, with its skipping rhythm could almost be another aspect of Pan. The set closes with Moonlight with a placid melody surrounded by a scudding cloudscape, the mood hardly disturbed by the occasional faster flowing arpeggios.

The three Sonatines by Sibelius were written just after the fourth symphony. All have three movements and are very concise – the longest lasts just 7 minutes. The opening movements are contrapuntal and have an improvisatory feel, especially the first and third with their pastoral themes.

There is a yearning sadness to all three slow movements; the first hymn-like and if the opening of the second is a little reminiscent of the familiar D-flat romance its gentle barcarolle is more restrained. The third is a funeral march that leads straight into the finale, described in the booklet as “rather like a baroque gigue” which fits with the 6/8 time signature. For me, the overriding feeling is of triple rather than duple time. That said, it is as joyful as any of the three final movements, matching the delightful moto perpetuo of the first with its dazzling arabesques and the second’s jaunty dance. Finlandia needs no introduction, though it is not often heard in the terrific arrangement for piano published by Breitkopf and Härtel four years after Robert Kajanus conducted the first performance of the work in its final version.

Terhi Dostal studied at the Sibelius Academy, Hannikainen and Merikanto’s stamping ground and makes a speciality of introducing Finnish piano music to a wider audience. Her previous CD Finnish Impressions (ALBA ABCD514) featured works by Sibelius, Hannikainen, Helvi Leiviskä and Dostal herself. She has also recorded piano quartets by Hannikainen, Leiviskä and Armas Launis (Telos Music TLS228). Dostal is a worthy champion of this music with a sense of colour and texture that shines through from the very opening pages of the variations where she eagerly embraces their quixotic moods. She excels when passionate virtuosity is called for, but is equally at home in Merikanto’s impressionism, creating a wonderful sense of space and atmosphere.

Rob Challinor

Help us financially by purchasing from