William Wordsworth (1908-1988)

Piano Sonata in D minor, Op 13 (1938-1939)

Ballade, Op 41 (1949)

Cheesecombe Suite, Op 27 (1945)

Valediction, Op 82 (1967)

Thomas Wilson (1927-2001)

Incunabula (1983)

Edward McGuire (b. 1948)

Prelude 7 (f.p.1983)

Six Small Pieces in C major (1971)

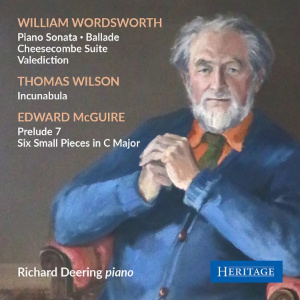

Richard Deering (piano)

rec. 1985, University of Wales, Cardiff, UK; 2023, Wyastone Concert Hall, Monmouth, UK (Sonata)

Heritage HTGCD142 [77]

Like London buses, recordings of William Wordsworth’s piano works come in pairs. Only a few weeks ago, I reviewed Christopher Guild’s disc with Wordsworth’s complete piano music on Toccata. Much earlier, in 1963, this repertoire was released on Lyrita (RCS13); Margaret Kitchin played the Ballade, the Sonata and the Cheesecombe Suite. There was a 2008 reissue on CD (review). In the late 1980s, Richard Deering published a cassette tape of Scottish Piano Music on the British Music Society label (BMS 407), with all pieces here except the Piano Sonata. (The title notwithstanding, only Edward McGuire was born in Scotland.) Paul Conway’s essay gives details of Wordsworth’s life and achievement.

Musicologist Lisa Hardy published the definitive book The British Piano Sonata, 1870-1945, Boydell Press, 2012. She wrote the liner notes for Wordsworth’s Sonata here. The work was completed in 1939 but not published until 1984. That is, Margaret Kitchin must have made her 1963 recording from the holograph.

The half-hour Sonata’s first movement – as long as the other two combined – is emotionally complex and diverse. The opening ghostly Maestoso is soon complemented by a vigorous Allegro deciso. A “calm and intimate” Allegretto leads to an overwrought development section with many changes of temper and pace. Towards the end of the movement, there is a reprise of the “calm” music before it comes to a caustic conclusion.

As I noted in my Toccata review, Harry Croft-Jackson – who wrote notes for RCS13 – likens the ominous slow movement Largamente e calmato attacca to “a deeply felt, contemplative landscape” with the “quality of a John Piper water colour”. I think it is a a good metaphor. The last-movement Allegro molto follows without a pause. Hardy observes that it suggests a military march. Maybe; for me it is dance-like with its insistent rhythms. There is a reprise of the “intimate theme” from the fist movement before the march/dance theme brings the Sonata to a vibrant conclusion.

The parameters are romantic, with an occasional nod to Bartók’s acerbity. This “epic and emotional work” deserves a place alongside Frank Bridge’s Piano Sonata from 1921-1924. Both were conceived as a “response to war”; both men were pacifists. Richard Deering, in a superb account of this powerful piece, brings the stylistic threads together in a satisfying unity.

During the Second World War, Wordsworth was sent to work on a farm near Alton, Hampshire. This was in lieu of military service, as he was a conscientious objector. He met his wife Frieda there, and made many acquaintances. The Cheesecombe Suite is dedicated “To my friends B.A., C.A., D.C., and G.E. whose initials provide the theme for these pieces”. Using these scalar “letters”, he created much of the musical material for this absorbing work. A thoughtful Prelude is followed by a quicksilver Scherzo. Then comes a deliberately unbalanced Nocturne; the despairing middle section is surrounded by a restrained presentation of the theme. The final movement, a moderately paced Fughetta, is not academic in any way. From a quiet statement of the subject, it moves to a vivid but hasty conclusion. The name Cheesecombe may refer to a farm near Lyme Regis where Wordsworth also did agricultural war-work.

The Ballade was dedicated to pianist Clifford Curzon. Wordsworth gave no explicit programme, but Harry Croft-Jackson’s comment is apposite: “the harmonic freedom, rhythmic variety, and, in the closing pages, restrained tension leaves the listener in no doubt as to the temper of the work – [it] matured in a period of conflict”. The Ballade seems to move from angst to resolution, by way of a stormy introduction, a short soliloquy, followed by an energising and intense Allegro con brio before it closes in a relative whisper. One can hear recollections of Bax and late Brahms.

The eight-minute Valediction is a journey rather than simply a lament. Wordsworth wrote it after the death in a car accident of his friend, the socialist activist Joe Green. In the composer’s words, “the mood changes from the backward-looking idea of a lament to an affirmation of the survival of the spirit of a good man”. The listener will be beguiled by Wordsworth’s use of “the kind of music played by a Highland piper at the burial of a hero”. It was dedicated to the pianist-composer Ronald Stevenson who gave the first performance. This deeply felt piece hovers between romanticism and a Scottish vernacular. It is mournful and heart-warming at the same time.

Thomas Wilson’s Incunabula had its origins in an idea in his 1983 song cycle The Willow Branches. In 1984, it was deployed into the Piano Concerto: musical recycling! The title means “the earliest stages or first traces in the development of anything” (Oxford English Dictionary). Interestingly, it can also mean “books produced in the infancy of the art of printing; especially those printed before 1500” and “the breeding-places of a species of bird”. The liner notes insist that it is the first meaning. Certainly, its progress would confirm that evolving concept. The six sections seem to grow or blend into each other, with no obvious recapitulation of material, but echoes of previous figurations may become more obvious with a score in hand. Typically introspective, Incunabula has moments of stress, but never becomes unbearable. It was composed for Richard Deering, who premiered it in 1984.

Edward McGuire’s Prelude 7 was another Deering commission. McGuire says that it reflects his interests at that time: the recently new-fangled fad for Minimalism, and allusions to Gaelic folk song. The piece would appear to have been included in the first of his two sets of 24 Preludes, many of them composed between the 1970s and 2015. They are for a wide range of instruments, including accordion, clarsach and castanets. The second set, according to McGuire’s website, would appear to be an ongoing project.

The Six Small Pieces are also products of McGuire’s interest in minimalism, with prominent nods to Erik Satie and John Cage. There is significant beauty in these miniatures, simple but subtle and nuanced.

The liner notes by Lisa Hardy, John Dodd and Edward McGuire give the listener all the information one need to enjoy this programme. I am beholden to them in the preparation of this review. There is a brief resume of Richard Deering’s career. The recording is exemplary, both the new one of the Sonata and the 1985 one of the other works.

It is an obvious question: which of the three recordings of Wordsworth’s piano music is th ebest? Margaret Kitchin’s recital was recorded mono. A contemporary analysis suggested that “the first two movements [were] lacking in impetus” and that the break between the end of the second movement was misjudged: it should “drive loudly and unhesitatingly into the pianissimo of the Allegro molto [finale]” (The Gramophone, June 1963). Christopher Guild and Richard Deering avoid such criticism. Yet, the early recording was a landmark of its day, and I am guessing that it was had the composer’s blessing.

A point in favour of Guild’s recording is that it includes the undated Three Pieces for piano and Wordsworth’s contribution to the didactic Five by Ten. It is truly a comprehensive edition. On the other hand, I was most impressed by Deering’s performances of this music, and that of McGuire and Wilson. As an enthusiast of William Wordsworth, I would wish to have all three versions in my collection. It is rare that three outstanding pianists devote so much attention to a less known composer.

John France

Help us financially by purchasing from