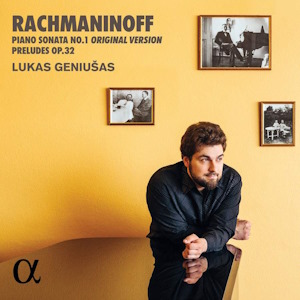

Sergei Rachmaninov (1873-1943)

Sonata No. 1 in D minor Op28 (original version)

Preludes Op32 Nos. 2,7,8 & 13

Lukas Geniušas (piano)

rec. 2023 , Villa Senar, Weggis, Switzerland

Reviewed as a digital download from a press preview

Alpha Classics 997 [55]

The career of Lukas Geniušas has been bubbling away for some time and with every succeeding release I find myself wondering if this is the one which will get it to come to the boil. Perhaps the special circumstances around this contribution to the Rachmaninov 150th anniversary celebrations will put him into the spotlight where his talents so richly deserve to be. Those circumstances are twofold: first, it was played on a piano presented to the composer on the occasion of his 60th birthday by Steinway and recorded in Villa Senar, the property he had built for himself in Switzerland; secondly, this appears to be a first recording of Rachmaninov’s own original manuscript before this huge work was subjected to extensive cuts. Both add excitement and interest to an already excellent recording.

The trouble with this sonata is that it is loose and rambling but loses its many virtues if hacked up in the interests of making it more concise. Its diffuse nature is the price one pays for its glories. Quite apart from anything else, Rachmaninov’s inspiration needs a big canvas. Two works by Liszt hover behind the work which was roughly contemporary with the equally big-boned Third Piano Concerto: the B minor sonata; and the Faust Symphony. Whether or not the story that Rachmaninov had a programme in mind with the sonata’s three movements representing Faust, Gretchen and Mephistopheles respectively is true there is definitely something of the mood of both Goethe’s original and Liszt’s take on it about the sonata in its original form.

Probably even more influential on both the structure and the style of the sonata, Liszt’s only piano sonata can be felt in virtually every bar without it ever sounding anything other than Rachmaninov. If it could only have one author, it lacks the big melodies of his more famous works, evolving through motives rather than tunes in the manner of the Liszt sonata. As a consequence, it is a denser and less immediately appealing work than its successor. On the other hand, it might be seen as the precursor of the similarly motive-driven, more modernist works of the later American period though without their concision.

As caught by Alpha’s generous engineering, the sound of the piano is intriguing in itself. Despite possessing the familiar fingerprints of the modern Steinway, it almost has a period instrument quality to it – certainly as recorded in the Villa Serna. It is always a tricky business to separate out how much of a contribution has been made to the sound we hear on the final recording by each of the pianist, the engineer, the piano and the acoustic. Suffice it to say that all of their efforts add up to a wonderful mellow sound like the soft bouquet of a well-aged red wine – full bodied but with a touch of oak on the palate. It isn’t hard to imagine that this was the sound heard by the composer as he worked on his later scores. None of the works on this recording was written at the Villa but they fit the piano sound in almost ideal fashion. Geniušas can thunder away at handfuls of chords with the best of them but the sound never becomes ugly or hard.

Geniušas is in many ways the ideal pianist for this sonata. He is the model of the modern Rachmaninov pianist, blending rigour and intellect with just enough earthy Russianness to stop the score sounding too prosaic. If Geniušas is not a barnstormer like someone like Trifonov, he doesn’t lack big guns. The glory of his pianism is his capacity for dreamy poetry – just as essential a part of the composer’s musical DNA as ferocious octaves. The subtlety of the rubato at the end of the slow movement combined with a delicately refined touch will have anyone who loves Rachmaninov wondering why this work isn’t better known.

As ever with Geniušas he is a master of ‘orchestrating’ piano music with a vivid range of tone colours. This is immensely helpful in filling out what is a complex and rather orchestral main work. At the opening of the finale it is not hard to hear trombones and cellos and basses in its thundering rhythms – and flutes and violins in the delicate tracery of the movement’s second subject.

The programme is filled out – not particularly generously it must be said – with four of the Op32 preludes. Geniušas makes an oblique reference to “the original editions of the Op32 Preludes” but goes no further in explaining whether he is using a rare version of these pieces. The pieces chosen, written a few years later, complement the main work perfectly.

This is splendid playing in every way, full of colour and daring and scholarship. Whether it is the break out recording Geniušas’ career merits I couldn’t say – I picked this from the release schedule on account of the pianist not the programme – but Rachmaninov enthusiasts are in for a treat.

David McDade

Previous review: Roy Westbrook (November 2023)

Help us financially by purchasing from