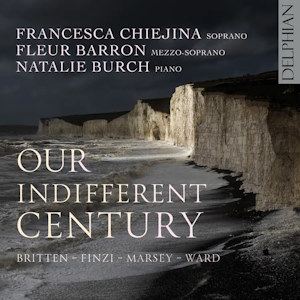

Our Indifferent Century

Benjamin Britten (1913-1976)

On this Island, Op. 11 (1937)

William Marcy (b. 1989)

Removal and other powers

Gerald Finzi (1901-1956)

Before and After Summer

Joanna Ward (b. 1998)

SUMMER DRESSES/STRANGER-FRIENDS (bean piece 5)

Francesca Chiejina (soprano)

Fleur Barron (mezzo-soprano)

Natalie Burch (piano)

rec. 2022, Greyfriars Kirk, Edinburgh

Sung texts are provided in the booklet

Delphian DCD34311 [64]

The title of this collection is taken from Channel Firing, one of the Thomas Hardy poems Gerald Finzi set in Before and after Summer. The corpses lying in a churchyard are disturbed by the noise of gunnery practice in the English Channel, and one of them is moved to muse on the state of the world in ‘our indifferent century’, wondering if things will ever get better. Lucy Walker, in a thoughtful booklet note, makes a valiant effort to establish a link between the four very different works that make up this programme, one that will support the thesis and thereby validate the title.

On this Island was composed, like the earlier Our Hunting Fathers and the slightly later Les Illuminations, for the soprano voice of Sophie Wyss. The five songs are settings of W H Auden, an important figure in Britten’s life at that time who acted as a kind of mentor in both artistic and personal matters. Our Hunting Fathers and Paul Bunyan, the composer’s first work for the operatic stage, were also settings of words by Auden. Our Hunting Fathers created something of a stir at its first performance, but On this Island is an easier listen, less confrontational both in its music and its subject matter. For some, it feels like a step back, for others a conscious effort on the young composer’s part to engage with his listeners. Francesca Chiejina has the full measure of the work. She is equally at home in the coloratura of the first verse of the opening song, ‘Let the florid music praise!’ as she is in the reflective, cantabile second verse. She finds the right tone of irony in the second song, and the cheeky, relaxed cabaret/jazzy drawl necessary for the final ‘As it is, plenty’. The words are, for the most part, very clear – this was apparently not the case with Wyss! – though careful reading of the text is required, as always with Auden, to draw out the theme.

Francesca Chiejina is joined by Fleur Barron for William Marsey’s Removal and other powers. The subject of this work was topical when the disc was recorded and is even more topical and controversial as I write. The text is taken from the Immigration Bill introduced into the House of Commons in October 2013, alongside a statement from the Home Secretary expressing the opinion that the Bill is compatible with the European Convention of Human Rights. So far, so unpromising, and yet… A lilting, triple-time introduction featuring a falling two-note motif that sticks stubbornly in the mind leads into the first extract from the Bill, where one voice takes over the motif. The composer’s word-setting technique is unusual: words and syllables are split in unexpected ways, and further into the work all pretence at audibility is abandoned as both voices throw in fragments of the text apparently at random. The Home Secretary’s declaration restores some unity, and this is followed by a piano postlude that is ostensibly jubilant but which most listeners will hear as ironic commentary. The lilting figure returns to end the work. Marsey has achieved something close to pathos in this short and highly unusual piece. It is beautifully sung by both singers.

The text of Joanna Ward’s SUMMER DRESSES / STRANGER FRIENDS – the capital letters appear to be obligatory – was written during the pandemic lockdown by the composer’s younger sister, Laurie. We hear, as the booklet note tells us, indoor sounds such as ‘buzzing tones of electric fans’ and ‘noises of washing up’. There are also a couple of disconcertingly sudden silences. The poet is indoors, then, but in her poem she is observing a bucolic scene with ‘skirts wide and hearts full’, ‘voices of pals’ and ‘marigold smiles’. We read that the performers frequently ‘sing and play their parts in freestyle rhythm’, and that ‘the score is occasionally notated in sketches’. The words are once again delivered as much for their sound and their place in the voice as for their meaning. ‘Wistful and slightly uncanny’ is how Lucy Walker describes this music, to which I would add a powerful feeling of summer heat, though quite where in the music that sensation originates is impossible to assert. I leave purchasers to read the explanation of the work’s subtitle.

The ten songs that make up Finzi’s Before and after Summer are settings of poems by Thomas Hardy, a poet to whom the composer frequently turned. They were composed at different times and gathered together later for publication. This is not a song-cycle, then, but there is some unity of mood, and it is predominantly sombre. Hardy’s poems frequently begin with a kind of scene-setting that leads us, in the final lines, to a melancholy conclusion about the past and the future, about life and death, and about love and loss. Finzi responds willingly to such a world view. The longest and most imposing song, ‘Channel Firing’, was composed in 1939, and Diana McVeagh has described it as ‘Finzi’s denunciation of war on the innocent’. Interestingly, Finzi himself wrote that ‘One has to choose between recognition of the absolute insanity of all war & recognition of the necessity of this particular one.’ At over six minutes, it is a large-scale setting of a long poem, an exchange between the dead, whose churchyard slumbers have been disturbed by the sound of the guns, and God who attempts to explain it away. Violent chromaticism evokes the wartime scene, and it rather hides any attempt at musical differentiation between the speakers. The set as a whole seems rather monochrome compared to others in the Finzi canon. Several of the poems hardly lend themselves easily to musical setting, and nowhere will you find here the rapt wonder of ‘The Comet at Yell’ham’ or the gentle acceptance of mortality in ‘The Dance continued’, to cite only other Hardy settings. The songs were conceived for baritone, but Fleur Barron’s rich mezzo is ideal, and she makes a wonderful job of them. It is clear from the opening song that assertiveness will be one of the qualities she will bring to her performance. She takes her cue, no doubt, and quite rightly, from the overall atmosphere of the set. Yet she adopts a pleasing simplicity of utterance for ‘Amabel’, and more particularly still for the preceding ‘Epeisodia’, a performance of exquisite lightness. If the songs appeal, so will Barron’s singing of them.

Binding the whole recital together from the keyboard is pianist, Natalie Burch. In fact, a detail in her biography leads one to suspect that she may have planned the programme. Her playing throughout is very fine indeed, full of character, whether it be in forceful passages or in the more transparent, flowing textures that run in and out of the vocal line in some of the songs. She is totally at one with the singers, but you never forget she is there. All this is, I believe, the mark of a great accompanist.

William Hedley

Help us financially by purchasing from