Felix Mendelssohn (1809-1847

Symphony No. 3 Scottish (1842)

Symphony No. 5 Reformation (1830)

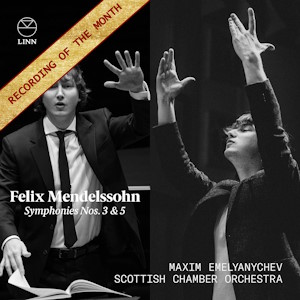

Scottish Chamber Orchestra/Maxim Emelyanychev

rec. 2022, Caird Hall, Dundee, UK

Linn CKD667 [65]

Maybe I’m biased: I live in Edinburgh, after all, which makes the Scottish Chamber Orchestra my home band. Furthermore, I go to hear almost every concert they play because I’m a huge fan of their work, particularly when they perform with their Principal Conductor Maxim Emelyanychev. But even taking all that into account, I’m certain that this disc is a bona fide triumph, a superb Mendelssohn set that showcases sensational orchestral playing, a triumphantly successful vision, and a completely compelling vision for the composer’s symphonic music.

It helps that the orchestra uses period brass and timpani for these performances, and the strings play with minimal vibrato. That isn’t a magic bullet, but it has a knockout impact in this recording, and you can tell you’re in for a treat right from the opening bars of the Scottish Symphony’s slow introduction. There’s a lithe, almost raw sense of leanness to the string sound, which gives the opening A minor lament a sound of yearning that’s almost on the level of desperation. The gains in transparency that this sets up are palpable, and keep reaping benefits throughout the whole disc.

However, it’s what you do with the period sound that matters, and this is where we perceive the benefits not only of Principal Conductor Maxim Emelyanychev’s acres of experience in the historically informed field, but in his long relationship with the orchestra, because he shapes the sound with remarkable care and attention to detail, and the musicians meet every aspect with hair-trigger responsiveness and excited energy. You get all that as the third symphony’s opening leads into the main Allegro. Emelyanychev has the orchestra play the bouncing main theme so softly that you almost have to strain to hear it, and then it imperceptibly picks up the pace as it leads into the first big orchestral tutti. There’s a terrific kick to the wind and brass playing, which balances the strings beautifully, and that gives the development an extra edge of whirling energy. The orchestral transparency, the Linn engineers and the Caird Hall acoustic combine to make everything audible, and the effect of this is often remarkable. Listen, for example, to the middle string line at the beginning of the recapitulation, which hovers delicately alongside the violins’ restatement of the main theme, delivered with delectable colour while being subtly integrated into the overall sound picture.

The thunderstorm of the first movement’s coda whets the appetite for a terrific skirl of a Scherzo, which whirls its way along with foot-tapping energy. The slow movement’s main violin melody feels like a gently swaying song-without-words, and its stormy interruptions turn it into a dramatic conversation. The finale then storms its way forwards, emphasising the Scotch snap element of its main melody with razor-sharp precision. Those lean strings contrast with percussive winds, and the whole gathers up a terrific head of steam as it brims over into the major key coda, pausing via a poignantly beautiful pair of solos from the orchestra’s principal clarinet and bassoon on the way.

As performed here, the Scottish Symphony takes on the air of a properly dramatic symphony, along the lines of Beethoven’s Fifth or even Berlioz’s Symphonie Fantastique. You feel you’re in the hands of master storytellers unfolding a gripping narrative before your ears, moving through moods and scenes with propulsive energy, and it makes you wonder why Mendelssohn’s symphony isn’t always performed with such thrust and passionate drive. It’s a revelation, and the brilliant thing is that the way they play the Reformation Symphony is every bit as good.

The opening contrasts those lithe string sounds with portentous-sounding fanfares from the brass and winds, out of which the Dresden Amen emerges with rapt spiritual intensity. The main theme is curt and decisive, and develops in a manner every bit as war-like as the finale of the Scottish. The orchestral whirl as the development reaches its climax is exhilarating, and the main themes in the recapitulation are treated with surprising subtlety and softness. The coda has a real sense of the battle having been won, a triumphalism that vanishes into thin air in the Scherzo, played here with such lightness that it sounds like it could have been lifted from the fairy scenes of A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

The slow movement returns to the keening intensity we heard in the introduction to the Scottish Symphony. It’s a brief movement, but I doubt I’ve ever heard it played with such ineffable sadness as here. It resolves itself into a straightforwardly confident flute solo to introduce Luther’s chorale theme, and this builds up a head of steam with a pleasing sense of purpose and focus so that by the time we’ve got to the end of its first iteration, only a minute into the finale, it feels like Mendelssohn has already taken us on a journey of revelation. When I heard this team perform this symphony in concert I said that Emelyanychev structures this finale as though the chorale theme is slowly being filled out like the wind filling a sail. That’s every bit as tangible in this recording, but what also struck me is the sheer liveliness of the playing. This is religious triumph as a celebration, a source of joy, and the contrapuntal busyness that bubbles underneath only reinforces this, all the more so when it’s captured with such clarity by the recording engineers. The chorale’s final iteration feels like a terrifically assertive endpoint; a consummation, even, ending the disc on an exhilarating high.

So this is a great disc, worthy to set alongside this partnership’s previous recording, also on Linn, of Schubert’s Great C Major Symphony, which is just as excellent. My favourite Mendelssohn symphonies of recent years have been John Eliot Gardiner’s set with the LSO, but this SCO disc is more involving, more transparent and more consistently exciting. It isn’t so much a top choice for these symphonies as sui generis. It’ll change the way you hear Mendelssohn, which is perhaps the greatest compliment you can pay it.

Simon Thompson

Help us financially by purchasing from