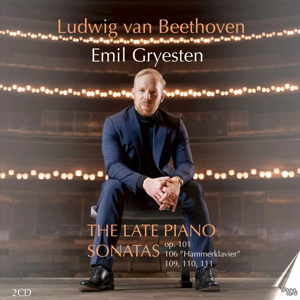

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827)

The Late Piano Sonatas

Sonata No. 28 in A Major, op. 101 (1816)

Sonata No. 29 in B flat Major, op. 106 “Hammerklavier” (1817-1818)

Sonata No. 30 in E Major, op. 109 (1820)

Sonata No. 31 in A flat Major, op. 110 (1821)

Sonata No. 32 in C minor, op. 111 (1821-1822)

Emil Gryesten (piano)

rec. 2023, Main Concert Hall, Royal Danish Academy of Music, Copenhagen, Denmark

Danacord DACOCD973 [2 CDs: 61+61]

Beethoven’s five late piano sonatas include the massive “Hammerklavier”, with enormous intellectual and technical demands on the pianist. Many regard it as the greatest of all piano sonatas.

This recording needs context, which I will draw, with thanks, from the booklet notes. During the Covid pandemic in 2020, most of Emil Gryesten’s concert and recital bookings were cancelled. He took this “opportunity” to create an artistic research project at the Royal Danish Academy of Music. The subject was Beethoven’s late piano sonatas. The study involved the application of the Schenker musical analysis system, a complex process that comprises musical theory as well as philosophical and psychological speculation. Briefly, the principle is that all tonal music can be reduced to three levels: 1) a background – basic harmonic progressions which underlie the piece or movement; 2) a middle ground – the elaboration of the first level which begins to give the work its identity; and 3) the foreground – the detail presented to the listener, with a little assistance from The Thames and Hudson Encyclopaedia of 20th-century Music by Paul Griffiths. The work under study is often reduced to its lowest common denominator and presented in diagrammatic form.

Gryesten writes that the aim “was to approach the scores with fresh ears, mind and spirit, allowing the chosen analysis method to function as the main interpretative lens, leaving behind the patinated baggage of tradition.” It is hoped that these studies will lead to revitalised and relevant new performances.

With the help of his colleague Thomas Solak, Gryesten applied the methodology to Beethoven’s late sonatas. The entire undertaking took two years and resulted in a “deep exploration of the scores and analytical graphs, consuming powerful doses of esoteric French philosophy”. Other outcomes of the project included “workshops for students, an international seminar on Schenker, some articles, a series of lecture recitals, and this recording”.

Gryesten does offer clues as to what the putative listener may expect: an “eclectic style” exhibiting “stylistic characteristics which could be heard as belonging to quite diverse epochs and styles”. He admits that there are “elements inspired by historical practice and a close reading of Beethoven’s scores”. The overall impact reveals a “romantic sentiment,” imbued with “occasional jazzy or modernistic details”. Finally, he refers the readers to an article which provides “a thorough explanation of the profound ways, in which a Schenkerian approach has shaped these interpretations”. (A link or a reference would have been helpful…)

The booklet is largely concerned with the rationale of the Schenkerian analysis and the subsequent reinterpretation of Beethoven’s late piano sonatas. Gryesten has chosen not to give an “extensive commentary” on each sonata, only some “observations” on each one. For further analysis and technical scrutiny, he recommends the texts by Charles Rosen, Donald Tovey, Edwin Fischer and András Schiff.

Emil Gryesten was born in Aarhus in 1985. He studied at the Jutland Academy of Music and later at the Royal Academy of Music in Copenhagen, the Sibelius Academy in Helsinki and finally, the International Piano Academy at Lake Como. His notable teachers included Niklas Sivelöv, Erik T. Tawaststjerna and Fou Ts’ong. Over the years, he has received numerous awards, including the First Prize at the Hamburg Steinway Competition. He has given recitals and concert performances in Scandinavia, Europe and the United States. He is the pianist in the Danish Trio Vivo. Recent recordings include Liszt’s Piano Sonata and Grieg’s Violin Sonatas with Benedikte Damgaard. He is assistant Professor of Piano and Chamber Music at the Royal Danish Academy.

Now, where does all this leave the listener? Does this “fresh approach” negate the important recordings by such virtuosi as Alfred Brendel, Mitsuko Uchida, András Schiff or Vladimir Ashkenazy? I am not a Beethoven enthusiast or cognoscente even if I enjoy, and hopefully appreciate, much of his work. When I wish to hear any one of the late sonatas, I turn to Alfred Brendel’s 1975 recording. This has always been sufficient for me.

So, will the typical Beethoven listener notice the difference between this recording and their usual fare? I am not convinced they will. I certainly did not, and I admit I have neither the resources nor the inclination to compare many versions. Unless one devotes time to a close reading of these sonatas with the scores and technical analysis, I guess they will just have to enjoy the playing.

My bottom line is this: did these performances move me, inspire me? The answer is a big Yes! This is a splendid recital, wonderfully played. I will leave the theoretical underpinnings to the experts and the pedants.

John France

Help us financially by purchasing from