Déjà Review: this review was first published in November 2004 and the recording is still available.

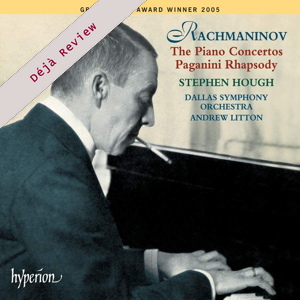

Sergei Rachmaninov (1873-1943)

Piano Concerto no.1 in F sharp minor op.1

Piano Concerto no.2 in C minor op.18

Piano Concerto no.3 in D minor op.30

Piano Concerto no.4 in G minor op.40

Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini op.43

Stephen Hough (piano)

Dallas Symphony Orchestra/Andrew Litton

rec. 2003/04, Eugene McDermott Concert Hall, Morton H. Meyerson Symphony Center, Dallas, USA

Hyperion CDA67501/2 [2 CDs: 146]

There was a time when cycles of standard repertoire came from the “greats” of the industry while the smaller companies delved into lesser-known fare. Curiously, Rachmaninov cycles have recently come from two of the smaller companies which, happily, nonetheless continue their explorations of the byways of music; that by Oleg Marshev and the Aarhus Symphony Orchestra under James Loughran on Danacord (review) and the present issue from Hyperion. To tell the truth, the former has been sitting on my shelves for a couple of years in multiple copies that I received as a result of having written the booklet notes, so this seemed a good moment to assess it together with Hough and Litton.

Certainly, the two offer remarkably different interpretations, so I hope that the following comments will make it clear to you which you are likely to prefer. In a certain sense, it could all be summed up by contrasting Hough and Litton’s total timing of 145:35 for the five works with Marshev and Loughran’s 165:38 – almost another concerto-worth of extra time and necessitating a third CD. However, Danacord offer the set at three for the price of two, so don’t let economic considerations worry you.

Another difference is that the Hyperion comes with a manifesto nailed to its door in the form of a preface by the pianist. I’m not sure this sort of thing is to be encouraged since it seems to me a form of “Solti-itis”, a word I derive from that incomparable knight’s practice, during a long career, of preceding his major releases with a plethora of interviews in which he explained how and why his forthcoming interpretations were superior to all previous ones. And there were many, critics included, who were hoodwinked into believing they really were so. In the same way, I have already seen some write-ups of Hough’s Rachmaninov (no reference to KS on this same site, though he is certainly more enthusiastic than I am) which have virtually taken Hough’s introduction, turned it from the first person into the third, and called that a review.

So let us examine some of his points. One regards the use of portamento slides in the strings. Now, if we take the first orchestral statement of the principal theme of Concerto 1, first movement, following the opening flourishes, it is evident that Litton has studied the Rachmaninov/Ormandy recording very carefully, for the same portamentos are reproduced in exactly the same places, and the same goes for a couple of fairly radical tenutos on single notes. As an exercise in style it is fascinating, even wonderful. I am not sure that the Dallas orchestra has quite the saturated weight of string tone commanded by Ormandy’s Philadelphia at its peak, though it is difficult to judge this on the strength of recordings made more than 60 years apart. There is no doubt that this band has acquired infinitely more bloom and depth of sound since it recorded the Symphonic Dances so dryly under Donald Johanos in the 1970s.

Fascinated as I was by the exercise, I wondered whether it was going to be a bit too much of a good thing in the course of all five works, but this was not put to the test since the orchestra evidently felt that, having done their duty towards early 20th Century stylistic conventions on those two pages, enough was enough and they revert to a typically modern, squeaky-clean manner of playing; if there are more than three or four portamentos in all the remaining four works put together I’ll eat my hat. There is no attempt, for example, to emulate Stokowski’s swooping strings in the 18th variation of the Rhapsody, to name one obvious point, and moments like the high-lying string writing at the end of the 4th concerto’s first movement or the lyrical theme in the finale of the 3rd seem to cry out for the odd slide here and there. Indeed, there are some unredeemed bands here in Europe (though not that of Aarhus) which still provide such things even without any declared agenda. Perhaps I would have made less of this point if it hadn’t been for the pianist’s declarations.

Hough also speaks of “the characteristic rubato of the composer’s playing”, the “flexible, fluent tempos, always pushing forward with ardour” and the “teasing, shaded inner-voices forming chromatically shifting harmonic counterpoint to the melody”. With regard to the latter, I didn’t honestly note any inner line which was brought out by Hough and missed by Marshev, though if you search the catalogue for unperceptive performances you will obviously find some. Turning to the “characteristic rubato”, it is again the first concerto in which Hough seems to be experimenting most systematically, offering numerous impulsive spurts countered by languorous hesitations, sometimes even to a greater degree than the composer himself. What I miss is Rachmaninov’s own ability to do all this while retaining a certain aristocratic detachment; in other words, Hough has reproduced the manner but not always the substance of Rachmaninov’s pianism. All the same, while the composer’s performance has a greater range, Hough’s mercurial approach has its attractions in a work which, though so heavily revised in 1917 as to form a harmonic bridge between the 3rd and 4th concertos, nevertheless retains its youthful character.

Hough has harsh words to say about many interpreters of the 2nd concerto: “To take too slow a tempo, with numerous ritardandos, for the first subject of the first movement of Rachmaninov’s Second Concerto means that one of the longest melodies in the repertoire becomes fragmented and earthbound”. This sort of sweeping comment, designed to evoke images of a host of unjustly famous ignoramuses vying with each other to muck up great music, is better avoided. Come on, Mr. Hough, who are these nitwits? Let’s have some names. Do you mean Richter? Rubinstein? Ashkenazy? I think we should be told.

In the event, Hough presents a swift, surging first movement, attractive but just a shade breathless. If one is going to preach stylistic awareness, I feel there are other things to be taken into consideration too. For a start, it’s marked “Moderato”. Now “moderato”, more than a tempo, is a mood, or an atmosphere. There is a certain range of tempi at which a “moderato” mood can be achieved and it may be that Rachmaninov could make this tempo sound “moderato”; I have to say that Hough’s tempo is, to my ears, “allegro”. Another issue is the metronome mark. Heaven forbid that such romantic music should be played metronomically but since the marking is there we may as well have a look at it, and in fact Marshev’s slower tempo is spot on, as were Farnadi and Scherchen (Westminster, long deleted), while Richter with Kondrashin was fractionally slower still, enabling the conductor to dig deeply into the various tenuto markings in the string melody. All of these seem to me to realize more satisfactorily the idea of “moderato”, and the melody is neither fragmented nor earthbound as they present it. Marshev uses the extra space to give greater weight and ardour to the music, and the suspicion arises that Hough’s faster tempi may derive from a lack real weight to his tone. In the lead-back to the recapitulation, for example, he fails to dominate the orchestra as Marshev (let alone Richter!) does.

At the same time, Marshev also has the measure of the melancholy poetry of the second movement, assisted by some long-breathed phrasing from Loughran and the orchestra. Hough again misses the spirit of the “Adagio sostenuto” marking – to my ears this is an “Andante”. Both pianists have a tendency to make a ritardando at the end of every bar in the early stages of the movement, something which Richter shows not to be necessary.

Still, my impressions were still positive at the end of the 2nd Concerto, but I’m afraid the 3rd left me quite unmoved. Hough begins the “Allegro ma non tanto” at about the tempo most pianists reach in the “Più mosso” section and the overall impression was that he was merely skating over the surface of the music, albeit it gracefully and pleasantly. This deplorably superficial account left me wondering if the music had not lost its appeal for me and it was actually at this point that I decided to try the Marshev cycle. Marshev and Loughran’s steadiness seemed a little homespun beside the fleet sophistication of Hough, but the music rang true, it seemed to well out of the composer’s soul, revealing those “six feet of Russian gloom” of which Stravinsky spoke. My faith in the music was restored. I also found the (studio) recording richer, clearer and more full-toned than the Hyperion and I wonder if recording live is necessarily such a good idea, even if you have such a distinguished producer as Andrew Keener in charge of the proceedings. In all truth, once a performance has been edited from a considerable run of concert performances, does it sound any more live than a good studio effort? These didn’t really sound like live performances and the burst of applause at the end seemed an unwarranted intrusion.

Concerto no.4 is a special case; derided from its earliest performances (in several versions), not even the composer’s own recording succeeded in planting it in the repertoire. That the work could be made to sound truly wonderful was demonstrated by Michelangeli in his sole Rachmaninov concerto recording, yet paradoxically this did nothing to revive the work’s fortunes in the concert hall. The impression was that Michelangeli’s own genius was at least as much responsible for the result, and lesser pianists fought shy. Marshev and Loughran make no attempt to imitate Michelangeli; they take the work steadily, at face value, and their sincerity shows it to be a powerful and rewarding work (it is actually my own favourite, but I seem to be alone in this). Basically, Hough and Litton do the same but, as is their wont, with faster tempi. Some may prefer this; I love, for example, the extra swagger Marshev and Loughran’s slower tempo allows them to find in the D flat section of the finale (two bars after fig. 49).

Hough’s Rhapsody, unlike the Concertos, is a studio recording and seems to benefit, with a clearer perspective (and transferred at a higher level) and with less tendency to screw up the tempi more and more than the pianist shows when playing live – something which might be very exciting in the concert hall but is not so good for repeated listening. In any case, Hough’s lightness and effervescence are harnessed to good effect in this particular work, especially when the famous 18th variation is by no means underplayed. If we compare Hough (02:57) directly with Rachmaninov (02:35) we find that, while Hough is not slavishly imitating the composer, he is recognizably playing the same music; turning immediately to Marshev (03:38) he almost seems to be playing something else. However, taken in context Marshev’s warmth and sincerity are moving. Overall Marshev gives a tougher performance, some of the ostinato variations suggesting parallels with Prokofief.

It must be clear by now that, of the two cycles, it is Marshev’s which I recommend. Taking the discs separately (which at present you can’t), Hough’s coupling of 1 and 4 with the Rhapsody has a lot going for it. Marshev’s no.1, which I haven’t mentioned so far, has the same leisurely ardour as the rest of his cycle and I thoroughly enjoyed it while thinking that perhaps Hough’s approach was preferably for this youthful music. But Marshev disappoints nowhere and is better recorded, whereas a cycle which has a superficial no.3 and a lightweight no.2 is not really in the running.

At which point one may ask if buying a complete cycle is the best solution, for a number of the best performances come from pianists who recorded only one or two of the concertos. You will probably seek the Richter/Kondrashin or Farnadi/Scherchen recordings in vain but Richter’s DG version with Wislocki is presumably available. Ashkenazy’s finest Rachmaninov concerto recording came, not in his cycle with Previn but in his one-off version of no.3 with Ormandy. Horowitz in no.3 was in a class his own, as Rachmaninov himself recognised. His last recording, with Ormandy, opened out the traditional cuts but even so it is probably the version with Reiner which represents him at his peak. The piano dominates the sound picture shamelessly, but in view of the massive sound Horowitz could get out of the instrument, this may not quite as unrealistic as is often supposed. Michelangeli in no.4 remains unrivalled.

By the way, some people might wish to insinuate that the fact that I wrote the booklet notes for the Marshev cycle makes me biased in its favour. Let me assure them that, having been duly rewarded for my work once I will receive no benefit, economic or otherwise, from future sales, reissues or the like and so have no reason whatever to push it except on the ground of its merits. Though of course, since my name is vicariously associated with it, I am pleased to find that it is a cycle which I can wholeheartedly enjoy.

Christopher Howell

Help us financially by purchasing from