Unveiled

Benjamin Britten (1913-1976)

Seven Sonnets of Michelangelo [sung in English] (1940)

Ruth Gipps (1921-1999)

Four Songs of Youth (1940)

William Denis Browne (1883-1915)

To Gratiana Dancing and Singing (1913)

Michael Tippett (1905-1998)

Songs for Ariel (1962)

Elgan Llŷr Thomas (b. 1990)

Swan

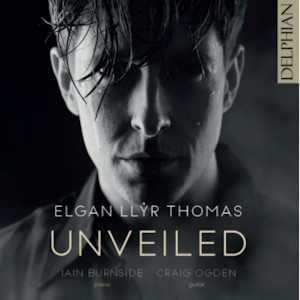

Elgan Llŷr Thomas (tenor)

Iain Burnside (piano)

Craig Ogden (guitar)

rec. 2022, St Mary’s Parish Church, Haddington, UK

Delphian DCD34293 [64]

Here is what Lucy Walker writes in the booklet: ‘Despite these constraints, however, running like a thread – or a stream – throughout this album is a fluid sense of freedom, or at least the potential for it.’ The constraints in question were the lot of Michael Tippett, Benjamin Britten and countless other creative artists: until a change in the law in 1967, homosexual activity was illegal and punishable by imprisonment. In a literary context, the critic John Lanchester is quoted as follows: ‘[for] the generation of artists who did their work in the closeted pre-Wolfenden climate […] the fictional treatment of same-sex love had to be implicit, indirect, deflected, latent’.

The argument goes that Britten followed this practice in his settings of Michelangelo, as did Tippett in his libretto for King Priam and the related Songs for Achilles, and the present soloist Elgan Llŷr Thomas in his own song cycle Swan which closes this recital. On the other hand, the link with Ruth Gipps’s songs seems rather tenuous, and even more so with the single song by William Denis Browne, Rupert Brooke being the connection. The album’s title presumably refers to the opening up in recent years of attitudes to homosexuality, though it could speak directly to the performance of Britten’s cycle, which is sung in English. More of this below.

There are few more startling moments in opera than when Achilles delivers his war cry at the end of Act 2 of Tippett’s King Priam. That cry returns in the second of the three songs he composed as a way of exploring the character further. The first song is simply Achilles’s aria transplanted from Act 1, where it is, as here, accompanied by a solo guitar. Guitarist Craig Ogden also accompanied Martyn Hill on a 1994 Hyperion disc of Tippett songs (CDA66749). Comparing the two performances is instructive, the second song in particular. Hill has a less conventionally operatic voice than Thomas, but he has no difficulty at all in making himself heard. For him, a fortissimo marking means making plenty of noise, but there is always something in reserve, perhaps for when the composer asks for an fff. Thomas’s performance leaves no doubt that Achilles is a warrior, yet already in the opening phrase of the first song he seems to attain the limit of his considerable vocal power. The forceful singing continues throughout the second song, so that the war cry has less dramatic effect than Martyn Hill’s.

Once again, a clue may be found in the booklet. About Swan, Walker writes that the work ‘has a palpably theatrical quality’ and that it was a deliberate policy on the part of the composer ‘to introduce his “operatic” sound into a recital context’. Paradoxically, it is in his own music that Thomas demonstrates his quiet singing, and it is very beautiful indeed. It is difficult to know quite what to make of the work itself, however, not helped by the fact that the words are not provided for copyright reasons. (Tippett’s texts are also absent.) Thomas enunciates with great skill, but following the cycle’s argument is a challenge, though the booklet draws attention to themes of ‘mental anguish’, ‘confessional coming-out’ and ‘hope of some kind of unification’. In an interview available online, Thomas is modest about his accomplishments as a composer. The opening song skilfully evokes calm waters, but the work as a whole is certainly derivative. It employs a conventional musical language for the most part, sometimes hymn-like, sometimes seeming to want to transform itself into the Moonlight Sonata. One song quotes the Bridal March from Lohengrin, while another, comically, brings in Swan Lake.

Britten’s youthful masterpiece, Seven Sonnets of Michelangelo, the first composed especially for Peter Pears, would seem to be the perfect example of what this album takes as its starting point – as shown in the John Lanchester quote above. Anyone who took the trouble to read the translations at the time would have understood at once that these were love poems. Now, sung in English, they are subject to their own ‘confessional coming-out’. I listened to the disc before opening the booklet, and the first phrase, sung to the English words ‘In every work of art, or so it seems to me…’ came as a shock. Yet this is a true singing translation, far removed from what can be found in those old opera scores many readers will have on their shelves. The booklet gives no information as to how it came about, but comparing it to a word for word translation reveals that Jeremy Sands has done a remarkable job. He retained the general meaning whilst producing a singable text. Overtly ‘poetic’ language is pretty much absent, however, and there are moments when the lofty tone of the original becomes rather conversational. There are other losses too: no English text can capture the chattering Italian of the penultimate song.

As for the performance, your reaction to the opening song will dictate, I think, how you feel about the whole cycle, and perhaps even the whole disc. Thomas has reason to be proud of the power he can generate in the upper regions of his magnificent voice, and no doubt the passion contained within the texts is sufficient justification, in his eyes, for the way he presents the work. But what this listener remembers from the performance is its sheer force, rather blotting out the many passages where the music’s impetuosity and delicacy is skilfully brought out by the singer. The poet seems overwrought, even angry. The fourth song suffers particularly in this respect, and a couple of sobs more appropriate to Romantic Italian opera – and questionable even there – seem misplaced.

The Gipps songs and Swan are listed as first recordings, as is the English version of the Britten. The booklet essay is interesting and sometimes challenging, and there are some attractive session photographs. No dates of composition are given, and the absence of information about Thomas as a composer or the provenance of the Michelangelo translations is frustrating. Iain Burnside’s playing is well up to his own exalted standards, and the sound, in a not too reverberant church acoustic, is very fine indeed.

In an interview on this site, Robert von Bahr of BIS has this to say about critics: ‘people should […] understand that a reviewer’s voice is but one voice and one set of opinions from one human being, with more or less taste and knowledge to back it up. No review is the truth, because there is no truth, just opinions.’ I am disappointed to respond negatively to Elgan Llŷr Thomas’s singing on his first recital disc, but surely others may well have a quite different reaction.

William Hedley

Help us financially by purchasing from