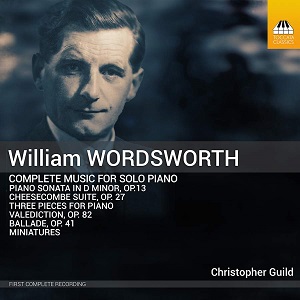

William Wordsworth (1908-1988)

Complete Music for Solo Piano

Piano Sonata in D Minor, op. 13 (1938-1939)

Three Pieces for Piano

Cheesecombe Suite, op. 27 (1945)

Selections from Five by Ten (published 1952)

Valediction, op. 82 (1967)

Christopher Guild (piano)

rec. 2021-23, Old Granary Studio, Beccles; Wyastone Hall, Wyastone Leys, UK

Toccata Classics TOCC0697 [81]

In 1975, Lyrita Records pressed again selected vinyl recordings from the 1960s. Those included piano music by Franz Reizenstein, Iain Hamilton, Michael Tippett, York Bowen, Lennox Berkeley and William Alwyn. I found a copy of Margaret Kitchin playing Wordsworth’s Ballade, Sonata and Cheesecombe Suite in the record department at Harrods. The album had originally been released in 1963.

For details of William Wordsworth’s life and achievement, see Paul Conway’s excellent study.

The Piano Sonata was begun in 1938, whilst Wordsworth was living at Hindhead, Surrey, and finished the following year. At that time, he participated in the activities of the Peace Pledge Union and the Hindhead Fellowship of Reconciliation. As the Second World War approached, he was confirmed as a conscientious objector.

The Sonata is large-scale at more than 30 minutes. The long and involved opening movement explores several musical lines of reasoning. It opens with a shadowy Maestoso, outlining some of the material which will be examined later. This is soon replaced by a vigorous first subject Allegro deciso. A more expressive second subject, Allegretto calms the entire process down. The development section is complex, with many changes of mood and speed. The recapitulation is regular. Despite a tender reprise of the first subject, the movement finishes with an acerbic coda.

Harry Croft-Jackson, who penned the original liner notes (Lyrita RCS 13), likens the ominous slow movement Largamente e calmato to “a deeply felt, contemplative landscape” with the “quality of a John Piper water colour”. This is a useful analogy. The Allegro molto finale is vivacious and dance-like. Reference is made to the opening Maestoso introduction before the Sonata ends with a scintillating coda.

Christopher Guild suggests that despite having “never been described as such in writing, it is difficult not to regard it as a ‘wartime’ sonata”. The historical locus of the work aside, I feel that overall it is positive; it tends toward romanticism rather than neo-classicism. Early criticism of Margaret Kitchin’s recording was that “the first two movements [were] lacking in impetus” and that the break between the end of the second movement was misjudged: it should “drive loudly and unhesitatingly into the pianissimo of the Allegro molto [finale]” (The Gramophone, June 1963). Guild has certainly ironed out these problems.

The Three Pieces were written in the early 1930s at Hindhead. The “overtly lyrical” Prelude has little angst, but has few nods to “pastoralism”. The Scherzo also lacks apprehension: it is quite simply playful from end to end, even the slightly more serious ‘trio’ section. The Rhapsody affectionately explores its theme with “long expansive gestures”. I can see landscape imagery. Perhaps Wordsworth was reflecting on the splendid views from nearby Gibbet Hill: on a clear day, one can see the London skyline.

The Cheesecombe Suite is dedicated “To my friends B.A., C.A., D.C., and G.E. whose initials provide the theme for these pieces”. It would be invidious to try to guess who they were. From these initials, Wordsworth generate a theme in “one long, languid phrase” at the start of the Prelude. The progress is sad and brooding. There follows a vivacious Scherzo, a relief from the meditative Prelude. There are several key changes and much rhythmic variety. The Nocturne builds from a nostalgic opening section through a hostile Poco piu mosso giving “a despairing cry”, before closing in a reflective disposition. The Suite is brought to a rip-roaring conclusion with a well-wrought Fughetta that builds up from a quiet statement of the subject, before surging ahead. One quirk is the sudden, abrupt ending. The soubriquet Cheesecombe may refer to a farm near Lyme Regis where Wordsworth did agricultural war-work in lieu of military service (see Paul Conway’s study).

The Ballade was dedicated to the pianist Clifford Curzon. There is no indication of any programme or literary allusion. The listener can provide the “story”. That said, Paul Conway (liner notes REAM 2106) has suggested that it does have a “narrative element, and the scale and heroic disposition of the [middle section] conveys the telling of an epic tale”. The Ballade is written in loose sonata form which may be perceived as a rhapsody. After a dramatic introduction, a quieter parlando (quasi recit.) section sets the scene. This leads into the thrilling Allegro con brio with considerable development. The opening theme is brought back, modified, and then closes quietly. The Ballade has been described as “stern but not wild” and for the most part “vehement” (I.K. Music and Letters, April 1955). Equally helpful is Harry Croft-Jackson’s comment (Lyrita, RCS 13) : “the harmonic freedom, rhythmic variety, and, in the closing pages, restrained tension leaves the listener in no doubt as to the temper of the work – this music matured in a period of conflict”.

It is rare for me to review a disc where I can play some of the music myself! In 1952, Lengnick issued a remarkable series of didactic literature: five graded albums for study and recreation, Five by Ten. It would be a disservice to suggest that they are simply educational. Any of these short numbers make splendid recital material for pupils ranging from Grade 1 to about Grade 6. The series was edited by Alec Rowley. The fascinating thing about these volumes were that they highlighted a group of British composers “popular” in the 1950s. These included big names like Edmund Rubbra, Malcolm Arnold, William Alwyn and Elizabeth Maconchy. There was a second group who are generally now only recalled by enthusiasts: Madeleine Dring, Bernard Stevens, Julius Harrison, Charles Proctor and Franz Reizenstein.

Somewhere in the middle was William Wordsworth. “Very easy to Easy” was his Bed-time (Six o’clock), complete with chiming grandfather clock and a sleepy goodnight. Equally elementary is the March of the Giants, a little galumphing modal tune. A Tale from Long Ago is gently contrapuntal. Book Two has a Bedtime Story, which is really like a very straightforward Bach Invention. Slightly more intricate is Ding Dong Bell, with its carillons ringing the changes. Moving on to “Moderately Easy to Moderate” in the editor’s opinion (!), Wordsworth contributes a Fireside Story, with not a few key changes. I would not rate Hornpipe from Book 4 as only “Moderately difficult.” Lots of neat little figurations and contrary motion to negotiate – but a fun piece to play. Snowflakes is deemed “Difficult”, with its broken chords and arpeggios. Certainly, as played here, it is impressionistic and evokes what a child may feel on a cold, snowy winter’s day.

This survey of Wordsworth’s piano music ends with Valediction. Wordsworth’s own short programme note says that he wrote it for composer, pianist and author Ronald Stevenson, in memory of a “mutual friend – Joe Watson – who was killed in a motor accident in 1966”. Watson, a blast-furnaceman from Consett, County Durham, had been involved with Frating Hall Farm near Colchester. This socialist institution had been set up in 1943 to provide farm labour for pacifists, as conscientious objectors, to remain within the law.

Originally to have been entitled Lament, the piece is inspired by “the kind of music played by a Highland piper at the burial of a hero”. Certainly, the sound of the pibroch and the pentatonic scale are apparent. Yet Wordsworth considered that as it developed “the mood changes from the backward-looking idea of a lament to an affirmation of the survival of the spirit of a great and good man”. He thinks, rightly, that “Valediction’ – ‘Fare thee well’ – is a better title”. The long, lugubrious piece successfully mourns and affirms at the same time. In 1969, Wordsworth arranged Valediction for full orchestra as op.82a.

Christopher Guild explains that he did not have access to the original score. He used a copy Ronald Stevenson made “for his convenience while it was in his repertoire, making pianistic changes to the layout for the hands, but not the notes themselves”. I will explain in a while why this is not a first performance (as the track listing claims).

The pianist gives a remarkable performance of this outstanding repertoire. He brings clarity, enthusiasm and commitment to the music. This is especially so in the immense sweep of the Piano Sonata: he imbues it with a massively consistent romantic breadth. The recording is first-rate.

Guild’s essay-length liner notes are detailed and informative (and much appreciated by this reviewer). Hidden behind the disc in the jewel case is an evocative picture of Glen Feshie in the Cairngorms, which (according to the booklet) Wordsworth could see from his study window. It is accompanied by a quotation: “I have always had joy in the grander aspects of Nature – mountains, storms, spacious views, and in the ever-changing colours of the Scottish Highlands.”

Whilst preparing this review, I listened to extracts from Margaret Kitchin’s 1962 Lyrita recording. Its old, grainy sound notwithstanding, it is a valuable performance. What came as a surprise was the discovery of a notice of a cassette tape of Scottish Piano Music issued on the British Music Society label (BMS 407) in the late 1980s (British Music Society News December 1988, p.13). That included Wordsworth’s Ballade, the Cheesecombe Suite and Valediction. Richard Deering also played works by Edward McGuire and Thomas Wilson.

I have not heard that recording. Deering’s webpage notes that Heritage Records are due to re-release this album (with extras) in September 2023.

John France

Help us financially by purchasing from