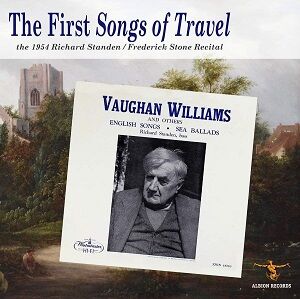

The First Songs of Travel

Richard Standen (bass-baritone)

Frederick Stone (piano)

rec. 1954, Westminster’s London Studio. (Originally released on Westminster XWN 18710 12” LP)

Texts included

Albion Records ALBCD055 [57]

This is a most interesting release from Albion Records which restores to circulation – and on CD for the first time – the contents of a generously filled Westminster LP. The collection is noteworthy because it includes what was (at that time) the first complete recording of Songs of Travel. Indeed, five of the eight songs here received their premiere recordings. A glance at the track list will show that the cycle is not presented as we know it today; there are two valid reasons for that. Firstly, ‘I Have Trod the Upward and the Downward Slope’, which we now know as the ninth song, was unknown at the time of the recording. VW had held it back and it was only discovered after he died in the year following the recording. (I’ve never quite understood the reason why VW withheld the song: after all, both thematically and emotionally, it wraps up the cycle.) In addition, Richard Standen opted to sing the songs in the order in which they were first published by Boosey & Co. The three songs, here designated as Part 1, were published together in 1905. Two years later, they published the other five. As Ronald Grames points out in his very valuable booklet essay, although the eight songs were performed in the order that VW intended as early as 1908, it was not until 1960 that the full cycle, now expanded to nine songs, was published in the order with which we’re so familiar. In preparing the recording for CD release Grames took the decision to retain the order in which Westminster presented them on LP and in which, presumably, the artists intended them to be heard; I think he was right to do so.

The featured singer is Richard Standen (1912-1987). As the booklet biography makes clear, he had a good career in the post-war decades, He also served for twenty years (1963-83) as a Professor at the Guildhall School of Music and Drama where I was interested to see that his pupils included Alistair Miles. He was noted for his performances in the field of oratorio but, though he was a recitalist too, this is the only surviving recording of him in the art song genre. His pianist is Frederick Stone. Little biographical information is available about Stone, it seems, though it is known that he worked a great deal for the BBC and that the artists he accompanied included Kathleen Ferrier.

My difficulty with this disc is that we have become so accustomed to excellence in the performance of art songs. In a moment I’ll consider Standen’s account of Songs of Travel in a bit more detail. However, as a general observation, in this cycle – and, indeed, elsewhere in his programme – he is far less imaginative in his delivery than the likes of Sir Thomas Allen, Christopher Maltman or Roderick Williams, to name but three. To my ears, he seems to do little with the words; all too often, his style seems to be ‘stand and deliver’. Generally, there is good attention to detail but even in this matter I feel he could do a bit more. Of course, one does not want the exaggerated dynamics which, in my view, so disfigured Bryn Terfel’s rendition of Songs of Travel on his 1995 DG album, The Vagabond; but the aforementioned three singers all show how intelligent use of dynamics and care for the words can bring songs to life in a way that seems largely to elude Standen. So, too, does John Shirley-Quirk who recorded for Saga in the 1960s the complete Songs of Travel and several of the other songs that Standen offers. Happily, all three of his Saga LPs have been gathered into a two-CD set by Heritage (HTGCD 283/4). I can’t see that we’ve reviewed this set on MusicWeb but the discs are well worth seeking out. Time and again, I’m afraid they show what is missing from Standen’s performances.

Standen’s account of ‘The Vagabond’ demonstrates both the strengths and weaknesses of his approach. His tone is firm, the voice forwardly produced, and his singing is consistently clear. So too is his diction; to our ears he may seem to exaggerate at times, notably in rolling the letter ‘r’, but I can live with that in order to hear the words clearly articulated. On the debit side of the ledger, though, he doesn’t seem to ‘do’ anything with the words and the sound of his voice is, to my ears, unvarying, with little evidence of different vocal colours. The contrast with Shirley-Quirk is stark. I think Standen’s way with ‘Bright is the ring of words’ is better; the opening is strongly declaimed, but then he fines back his voice effectively for the remainder of the song and I admire both the evenness with which the voice is projected and the security of his top register. ‘Let Beauty Awake’ is somewhat penny plain in delivery; I miss any sense of fantasy. A similar lack of imagination spoils ‘Youth and Love’; the ecstatic climax (‘Cries but a wayside word…’) is just a climax; ecstasy is notably absent. To be fair, ‘The Infinite Shining Heavens’ is better; here Standen is more expressive and evidences more care for the import of the words. I’m afraid that Richard Standen’s performance of these fine songs is a limited success.

Immediately after Songs of Travel we hear ‘Silent Noon’. By now I wasn’t expecting much, but Standen’s performance is really rather good. His observance of dynamics is excellent and he brings the words much more to life than was the case in Songs of Travel. If only he had sung the cycle in the same fashion, I’m sure I would have admired it much more. Even in ‘Silent Noon’ the sound of the voice itself is rather unvaried but the greater degree of imagination means that one doesn’t notice as much.

Moving on to the music of other composers, Standen offers all three of Frederick Keel’s Three Salt-Water Ballads. Of these, only the second, ‘Trade Winds’ is heard these days; I’m unsurprised, because the other two, which I can’t recall hearing before, are not in the same league. ‘Port of Many Ships’ is technically well sung but this is essentially a piece of light music and it needs a far defter touch than Standen brings: his singing is much too formal. The third song, ‘Mother Carey (as told me by the bo’sun)’ is similarly light-hearted. For all Standen’s clarity of diction elsewhere in the recital, he struggles to make many of the words clear – for which I’m inclined to blame the composer. (Interestingly, in Stanford’s ‘The “Old Superb”’ Standen’s words are much clearer which I think supports my view that Keel is at fault in the ‘Mother Carey’ song.) Standen does ‘Trade Winds’ well. I think he’s much better suited to this song, which is much closer to an art song than the other two in the set.

Standen’s accounts of the two Stanford songs are good. In ‘Drake’s Drum’ he uses dynamic contrast effectively and so brings the song to life. Both he and Frederick Stone articulate ‘The “Old Superb”’ well, though I have to record that John Shirley-Quirk, ably supported by Martin Isepp, is even more persuasive.

Standen gets good marks from me for including some unfamiliar fare in his programme, including two songs by Michael Head, both of which were new to me. I like to think that I have a reasonable knowledge of the English art song repertoire but two songs – and their composers – were completely unknown to me. I learned from Ronald Grames’ notes that Albert Mallinson composed over 400 songs and was the regular recital pianist for his wife, a well-known Danish soprano. Four by the clock may well have been written for her. It’s a song that is well worth hearing; the setting is dark and atmospheric. Standen sings it well and the deep bass in the piano accompaniment is very effective. Malcolm Davidson is a shadowy figure, though Grames has pieced together some biographical details for the booklet. A Christmas Carol sets the first two verses and the last one of a poem by John Masefield entitled Christmas Eve at Sea. As Ronald Grames observes, “The melancholy image of the forlorn sailor at sea on a still, moonlit Christmas Eve is indeed haunting”. That’s what Masefield portrays in the first two verses and I think that Davidson sets these words very well indeed. I’m less sure about the final verse in which the sailor enthusiastically proclaims the birth of Christ. This seems to me to make rather too swift a transition from both the words and music of the preceding stanzas and I’m not sure it works. Nonetheless, I’m very glad to have heard this song and the one by Mallinson.

Standen ends his recital with a much better-known sea-related song in the shape of Warlock’s boisterous Captain Stratton’s Fancy. This is a cracking song; it’s a great way to close a group of songs or a recital. I’m afraid, though, that Standen doesn’t really deliver the goods; he just ‘stands and delivers’, conjuring up in my imagination a provincial English bank manager of the 1950s performing a ‘turn’. That may sound cruel but listen to John Shirley-Quirk on the Heritage set and you’ll see what I mean. Shirley-Quirk, for example, brings a contemptuous sneer to the words ‘And some’ll swallow tay and stuff fit only for a wench’ whereas Standen just sings those words as he does everything else in the song; he completely fails to convey any of the entertaining relish with which Shirley-Quirk invests the song.

It’s been very interesting to hear Richard Standen’s recital. I admire some facets of his singing. I also salute him (and Westminster) for the enterprise of his programme; that applies not just to the premiere recording of the Vaughan Williams cycle but also some of the very unfamiliar fare towards the end of his recital. However, his style is far too plain spoken for me. All too often he fails to make the songs leap off the page in the way that so many other singers have done. I would describe the playing of Frederick Stone as reliable. He supports his singer well, but I don’t hear too many pianistic insights.

This project has clearly been a labour of love for Ronald Grames. He transferred the recordings from two LP copies of the 1959 Westminster reissue. He tells us in the booklet that, in the interests of fidelity (my phrase, not his), he made no attempt to remove noises inherent in the original recording. I made a point of listening through good quality headphones and I was completely untroubled by any extraneous noise. I’d say his transfers have been entirely successful. He has also written the extensive and scrupulously researched booklet essay; I found this absorbing.

Despite the reservations I’ve expressed, Richard Standen’s Songs of Travel merits a place in the VW discography and the production values of this Albion Records reissue present his recital in the best possible light.

John Quinn

Help us financially by purchasing from

Previous reviews: Nick Barnard (June 2023) ~ Jonathan Woolf (July 2023)

Contents

Ralph Vaughan Williams (1872 –1958)

Songs of Travel Part 1 (1905)

The Vagabond

Bright is the ring of words

The Roadside Fire

Songs of Travel Part 2 (1907)

Let Beauty Awake

Youth and Love

In Dreams

The Infinite Shining Heavens

Whither Must I Wander (1901)

The House of Life (1903): Silent Noon

Four Poems by Fredegond Shove (1922): The Watermill

Linden Lea

Frederick Keel (1871-1954)

Three Salt-Water Ballads (1919): Port of Many Ships

Trade Winds

Mother Carey (as told me by the bo’sun)

Michael Head (1900-1976)

Six Sea Songs (1949): Limehouse Reach

Sweethearts and wives

Sir Charles Villiers Stanford (1852-1924)

Songs of the Sea Op.91 (1904): Drake’s Drum

The “Old Superb”

John Ireland (1879-1962)

Sea Fever (1913)

Albert Mallinson (1870-1946)

Four by the clock (1901)

Malcolm Davidson (1891-1949)

A Christmas Carol (1920)

Peter Warlock (1894-1930)

Captain Stratton’s Fancy (Rum) (1922)