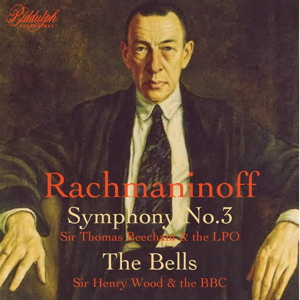

Sergei Rachmaninov (1873-1943)

Symphony No.3 in A minor, Op.44 (1936)

The Bells (1913)

Isobel Baillie (soprano), Parry Jones (tenor), Roy Henderson (baritone)

Philharmonic Choir

London Philharmonic Orchestra/Sir Thomas Beecham (symphony)

BBC Symphony Orchestra/Sir Henry Wood (The Bells)

rec. live, 18 November 1937 (symphony), 10 February 1937 (The Bells), Queen’s Hall, London, UK

Biddulph 85027-2 [69]

These are two privately recorded off-air broadcasts made by a man called Harold Vincent Marrot. He was particularly interested in Russian music and paid for professional recordings to be made of numerous works, including these examples, which pre-date any other known recordings, studio or live, of the Third Symphony or The Bells. In Rachmaninov’s 150th celebratory year, this is something of a coup for the collector of historic material.

Being nosey I wated to know what else he had recorded so I checked the catalogue of the British Library, where all his discs have been donated, and found a rich variety of music from Arensky to Balakirev via a swathe of Glazunov symphonies, presumably recorded in the wake of his death: at least four symphonies conducted by Richard Austin, Guy Warrack, and Leslie Heward. There also seems to be an anonymously performed Rachmaninov Fourth Piano Concerto from 1936-37 and Charles Lynch playing the First Sonata and much else. All food for further thought.

Beecham gave only two performances of the Third Symphony. This preserved one was given in Queen’s Hall on 18 November 1937, its European premiere, two years before the composer made his own recording in Philadelphia and one year after Stokowski had given the world premiere. It’s performed with exceptional dynamism and at just under 34 minutes is the fastest performance of the work I’ve come across. This intensity comes over as an intense lyric sweep with singing warmth, but without a sense of impatience or awkwardness. Beecham’s LPO plays with white hot intensity, their string slides infrequent but daringly noticeable when employed, the basses well caught, and the percussion similarly, though obviously not optimally given the off-air nature of the recording. Beecham doesn’t take the first movement exposition repeat but the composer didn’t take it either.

The opening of the slow movement sees the harp and brass accompanied by some surface scrunching but the solo playing is refined and affecting and when the music flares it does so with something approaching authentic Rachmaninovian flexibility. Rhythms are crisp, corners turned very quickly. From 9:48 to 10:04, as noted in the booklet, there’s transmission distortion – just before and also during David McCallum’s violin solo (his son, the talented and very musical actor of the same name, has just died). Beecham’s finale is again brisk but not brusque, the fugal writing splendidly realised, and a real festive sense is generated. I think some may find this all rather overheated but I liked it. Its sounds the me as if the BBC engineers controlled the volume as the work draws to a close, though fortunately, some of the raucous audience acclamation has been retained to refute the idea that Queen’s Hall audiences in the 30s routinely sat there like Elgar’s stuffed pigs.

There is some boomy overload in strident fortes and there is a constant sediment of surface noise but those experienced with such material will not find any of this either unusual or hard to take. It’s quite remarkable how much intricate detailing survives scrutiny and the atmosphere in Queen’s Hall is electric.

Beecham wasn’t known as a Rachmaninov interpreter and after the second performance he was never to return to this symphony but Sir Henry Wood – the antipathy between Beecham and Wood was near-legendary – was by contrast an admired proponent of his work of long-standing. Rachmaninov attended a rehearsal and performance of the Third given by Wood in 1938 and Wood had given the British premiere of The Bells in March 1921. At a 1936 performance in Sheffield, where Rachmaninov was playing his Second Piano Concerto, Wood unveiled the newly rewritten version of the third movement of The Bells, published separately, Wood noting that this movement was now ‘splendidly distinctive, full of colour, and easily ‘gets over’ the brilliant orchestral texture.’

For this Queen’s Hall performance in February 1937 Isobel Baillie, Parry Jones and Roy Henderson (substituting for Harold Williams) and the vast forces of the Philharmonic Choir were joined by the BBC Symphony Orchestra. It was sung in an English translation by Fanny S. Copeland. Wood seldom had much rehearsal time but this was a work that he had recently performed under the composer’s scrutiny and knew well and he gives a mighty performance of it, though I have to add that it’s not a work that appeals much to me. Parry Jones is on clarion form and there is a remarkable amount of orchestral detail to be heard, as in the Beecham, but with the added advantage that this is better recorded. You will certainly find the sheer mass of C Kennedy Scott’s Philharmonic Choir impressive. Wood takes fine tempi and no one would find them odd. Baillie is her accustomed pure-voiced self and she is well balanced against the orchestra. The second movement episode with the string pizzicati and bells is, for example, excellently realised by Wood and caught by the by the off-air recordist. The Presto draws from Wood his most combustible direction, the choir sounds powerfully charged and the BBC Symphony rivals Beecham’s LPO for individual and corporate style. One can hear the percussion more clearly here than in the Symphony recording whilst Wood measures the finale perfectly. He is often written off as a blunt practitioner, efficient rather than inspired, but he was far more than that as the quietly magnetic close shows.

This release has outstanding notes by the British Library’s Jonathan Summers, and Eric Wen. I’m not sure to what extent the transfers by Rick Torres are interventionist (or not) but they sound fine enough to me. These performances join the corpus of recordings made in situ at the Queen’s Hall, either commercially or live. This release also shows that there are still professionally made recordings from the 30s and 40s out there and that it’s both salutary and important that the performances they document are preserved in this way and that their custodians are generous enough to make them available, as is the case here.

Jonathan Woolf

Help us financially by purchasing from