Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750)

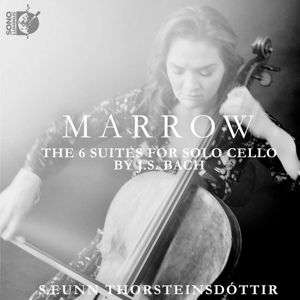

Marrow

Suites for Solo Cello Nos 1-6

Sæunn Thorsteindóttir (cello)

rec. 2021, Sono Luminus Studios, Boyce, USA

Sono Luminus DSL92263 [90]

British readers in particular might wonder why a recording of Bach’s cello suites bears a title more commonly associated with a fruit of the cucurbita pepo cultivar widely eaten as a vegetable and in these island often competitively grown; in fact, of course, it refers to bone marrow and, more specifically, as the cellist Sæunn Thorsteindóttir’s note informs us, derives from “an Icelandic saying ‘mergur málsins’, which directly translates to ‘the marrow of the matter’ and these Suites, to me, speak directly to the essence of being human”. So there you have it – and please excuse this rather laboured introductory explanation, but I feel the point needs clarification lest puzzlement ensue and folk feel inclined to submit my review to Private Eye’s “Pseuds’ Corner”.

One of my early contributions to MusicWeb was a review of EMI’s re-issue of Pablo Casals’ famous set; it was fairly comprehensive and much of what I wrote then still stands; I have since contributed several more reviews of further recordings of the cello suites and particularly enjoy David Watkins’ version on a period instrument in addition to the established, more Romantic accounts by Rostropovich, Fournier and Starker and more recent recordings by Nina Kotova and Alisa Weilerstein, all on modern cellos.

As such, this latest issue is up against stiff competition, as every cellist of note wants to set down his or her interpretation and there are probably something over 250 extant recordings . As ever, I tried to listen to this without prejudice. The first thing to note is that the suites are played here without repeats; Thorsteindóttir chooses not to stretch her audience’s powers of concentration, hence the comparatively short running time of ninety minutes – and I quite like the concision and approachability enabled by this decision. Sometimes movements are so comparatively brief that they seem to be over almost before they have started, like a flash of lightning searing the eyeball. Cellists seem to be divided about the desirability of repeats; some have made two recordings demonstrating that they have changed their mind, some include “embellished repeats”, some insist that they are required to preserve the symmetry of the binary form of the movements and others are adamant that they are redundant. My stance is that whatever choice is made, it must be done with conviction – and that goes for whether an artist chooses a more Romantic approach or inclined towards a sparer “baroque” style.

Beautiful sound, ideally distanced, perfectly deep and round, without annoying distractions like heavy breathing or fingerboard clicks is a distinct advantage, as per here. The opening suite is characterised by a lightness and momentum enhanced by the speed and dexterity of Thorsteindóttir’s playing – but she is equally capable of injecting an intense, soulful mood as in her rendering of the Sarabande, which is rhythmically free and flexible, with plenty of rubato. Her intonation is to my ear impeccable and the sonority of her tone striking. These suites are not dances, for all that their movements are named after dances and she does not try to impose too much rhythmic consistency as if they were; these are fluid, mercurial accounts.

The contrast between the first two suites is tellingly made; the listener will sense a complete change of mood in the keening, vibrato-free phrasing of the comparatively long Prelude of No. 2 and a tragic ambience is sustained throughout. The Sarabande is especially doleful and soulful. The Minuets hardly do anything to lift mood, their superficial insouciance being shot through with sorrow. The Gigue is similarly meretricious – no jolly “jig” indeed – such that the drive and nobility of the third suite comes as a relief. It is played with thrust and energy, pushing back the shadows lingering from the previous suite. Only the grand, unhurried Sarabande breaks that spell, being a kind of contemplative interlude; Thorsteindóttir ensures through her playing that the whole suite exudes a kind of majestic certainty until shafts of light break through in the concluding gigue, which is played forcefully but also with a due regard to dynamic variation.

That grandeur carries over through her playing into the fourth suite, my favourite. There is a massive, irresistible assurance to the manner in which she executes the runs of semiquavers in this most ebullient of the suites – although once again, the Sarabande sounds like an island of serenity amid the busy pomp. The fifth suite opens with trenchant double stopping akin to groans of pain which mutates into a restless outpouring of anguish, played here with great passion. The agony is unalleviated by the yearning Allemande, once more delivered with minimal vibrato and maximum melancholy, followed by a surprisingly short, tempestuous Courante before the emotional heart of the suite: the lamenting Sarabande before the dirge-like concluding movements – then Thorsteindóttir embraces the sunlight of the sixth suite, lightening her tone, soaring aloft and singing in the moto perpetuo Prelude, while displaying admirable dexterity and accuracy in the repeated arpeggios. The impression of the cello mimicking the human voice is sustained through the aria-like Allemande and the Courante is suffused with joie de vivre before the contented Sarabande, the cheerful Gavottes and the cosy, folksy Gigue – in stark contradistinction to the preceding suite.

Anyone who wants to hear these masterworks in the best sound, exquisitely played and shorn of repeats – and thus perhaps more digestible and concentrated to suit a modern sensibility more inclined to appreciate the virtues of brevity – will find this issue ideal.

Ralph Moore

Help us financially by purchasing from