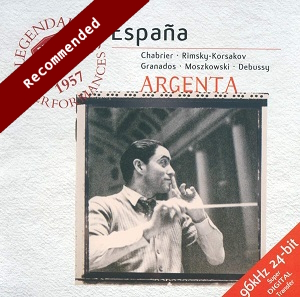

España

Emmanuel Chabrier (1841 – 1894)

España

Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov (1844 – 1908)

Capriccio Espagnol, Op 34

Enrique Granados (1867-1925)

Danzas Españolas, Op 37 No 5 in E minor “Andaluza”

Moritz Moszkowski (1854-1925)

Spanish Dances, Book 1, Op 12

Claude Debussy (1862-1918)

Images pour Orchestre

London Symphony Orchestra, l’Orchestre de la Suisse Romande (Debussy)/Ataúlfo Argenta

rec. January 1957, Kingsway Hall, London; May 1957, Victoria Hall, Geneva (Debussy)

Presto CD

Decca 4663782 [72]

Who remembers those hazy, crazy days of yesteryear, when heaven was a couple of hours spent rummaging through record-shop racks; or when a new issue was apt to provoke an anticipatory tingle? The latter would precipitate a frantic flurry of fiscal considerations: can I afford to splash out on the full-price record, or should I wait, hoping for an eventual reissue at medium-price – and possibly longer, on the off-chance it might descend to the “bargain basement” or (even better!) be unearthed in a stock-clearance sale? Of course, behind all this excitement lurked cold, hard corporate finance: it was the inevitable consequence of companies having to produce large batches of physical records.

In this digital age, when “records” are – or soon will be – all reduced to intangible binary files, there’s very little left of the aforementioned excitement, since deletion/reissue is – or soon will be – redundant. Worse, record collectors are – or soon will be – deprived of most of their pleasure, because, like most clans of collectors, they like to own things that they can “cuddle”. Their only option is to download binary files and use them to make their own cuddly CDs. However, while possible, this does require a fair bit of know-how – and in any case we still lose the thrill of the chase.

Presently, the dreadful prospect is held off by an intermediate alternative: with a relatively small additional investment, suppliers are able to run off individual instances of cuddly media “on demand”. This option has been around for longer than you might imagine (remember Nimbus doing something of the sort way back in 2002?), though how long it will continue, I guess, depends entirely on our old friends, market forces.

The good news is that these one-off CDs are virtually indistinguishable from their mass-produced counterparts, as witness this Presto CD that’s sitting on my desk right now. Sonically (the digital bits coming from identical files) there’s no difference; and only the slightly “blocky” print of the copyright notice, in exceedingly small letters on the disc’s label, gives any visual clue – which, need I add, is not exactly a dealbreaker, is it?

So, to the business in hand: this recording first appeared in 1957 (1958 for the stereo; why I’m not sure), by 1977 traversing the entire deletion/reissue spectrum. Oddly enough, for such a popular record, it had to wait until 1995 for its first CD issue (Decca 443580-2); and, only four years later, along came this Decca Legends remastering (466378-2), now available from Presto. However, these two CD issues are by no means identical.

Firstly, the Legends CD bears the boast-words, “96 KHz 24-bit Super DIGITAL Transfer”. On the face of it that sounds hugely impressive, but don’t let it fool you: all it boils down to is that the original analogue master tapes have been sampled to hi-res (24/96) digital, which has then been resampled at red-book (16/44) resolution for the CD. As such, it may be an improvement on a direct 16/44 digital transfer, but, at best, only just, and certainly nowhere near enough to warrant a handwritten communication to your domicile. Not that it particularly matters, because the 55-years-old original recording is straight out of Decca’s top drawer – hence, even a rough-and-ready 16/44 transfer will sound pretty good. So good was the sound that, back in the late 1950s, the original LP was much used as a “demonstration disc” by many equipment retailers, trying their damnedest to “sell” the newfangled stereo malarkey to a public that, not surprisingly, wanted to get its money’s worth out of its recently purchased mono equipment before replacing it by even more expensive stereo kit.

Parenthetically, I can still remember the owner of our local electrical shop demonstrating a stereo radiogram (anyone remember those?), explaining, “Y’ see, with stereo, the sound’s fuller; there’s moor boddy.” His potential customer countered with a cautious, “But I can get that just by turning up the volume, can’t I?” Unfazed, the dealer persisted: “Yes – but with stereo it’s got moor body as well.” It never crossed the dealer’s mind (possibly because he didn’t actually know?) that, to demonstrate the real difference, he just needed to get the customer to kneel in prayer before the machine, with his forehead almost touching the polished woodwork between the speakers – and then all the dealer needed do was to convince the punter that this was in fact a comfortable listening position!

Secondly and far more significantly, this Legends reissue supplements the original LP’s nearly 40 minutes running time with a substantial “filler” – another whole LP’s worth! – the same conductor’s reading of Debussy’s delectable Images pour Orchestre. The booklet includes nostalgic full-page reproductions of both LP sleeve-fronts, although, for some undisclosed reason, that of the Debussy LP is monochrome.

Ataúlfo Argenta (1913-57) is himself something of a legend. Having made a name for himself in Spain as a pianist, in 1941 he went for further study to Kassel in Germany (coming from fascist Spain, this was not a problem at that time); it was here that Carl Schuricht urged him to become a conductor. At the end of the war, already in his thirties, he did just that. Through consistent application and in spite of naggingly uncertain health, over the course of a mere 12 years he garnered a formidable reputation. Tragically, hovering on the very threshold of being hailed as a “great conductor”, he showed his utter ignorance of the consequences of sharing a closed garage with a car whose engine was running, and was lost to the world, aged only 44. Happily for us, he left a considerable recorded legacy; unhappily, relatively little of it was in stereo (and consequently possessed of “moor boddy”!).

Setting the filler aside for now, does this España album live up to all the “hype”? Well, I could simply say “yes” and leave it at that. However, as far as I can make out, this recording – in whatever incarnation – has never previously been reviewed by MWI, so it behoves me to delve a bit more deeply. First: recording quality. To put “Decca’s top drawer” into context, we should bear in mind what else Decca was doing in 1957! With legendary names like James Walker and Gordon Parry amongst the production credits, you’d have to be particularly picky to find any real faults with the sound quality, which is clear, rich yet detailed and, of its kind, quite simply gorgeous.

As regards the performances, Alan Sanders’s splendid booklet note reminds us that, “At this time the LSO was just emerging from a period as a fairly ordinary ensemble” (one infamous critic went so far as to say, “slovenly”); this quietly underlines the sheer magic wrought by the ministrations of the remarkable Spaniard. Technically, the playing is nigh-on faultless; only one wee blip succeeded in actually catching my ear. And as for interpretation, well, this album is a joy from start to finish.

In Chabrier’s España, the fine line between “too slow” and “too fast” is a tightrope that Argenta treads as to the manner born (which, come to think of it, he is). Nor does he mess with the tempo, instead generally allowing Chabrier’s shifts of pulse within that tempo to make their mark, and topping it all with pin-sharp accentuation – including pizzicati that positively prickle your eardrums – and almost “organic” dynamics. That aforementioned blip occurred near the start: in its brief solo, the harp suffered a teensy touch of finger-tangling. However, since I’ve often enough heard similar glitches in other renditions, I’m hardly inclined to be upset by it. The numbers of good recordings of España are legion; nevertheless, whatever your favourite, I’d suggest that this one, thoroughly well-thought-out and correspondingly thrilling, is worthy to share its slot in your affections.

If anything, Rimsky-Korsakov’s Capriccio Espagnol is even more often recorded and yet, in my experience, there are remarkably few out-and-out duds. My experience? Well, this piece has abided in my affections ever since I first heard it, on only my second LP purchase – way back in 1960. My experience tells me that Argenta’s effort is entirely antipodal to the dud-zone.

I could go on about, say, Argenta ensuring the consistent audibility of the castanets, neither treating them as a concerto soloist nor letting them be drowned in the tumult; or him bringing out – but without any undue exaggeration – the violins’ guitar-like strumming in the Alborada. But I won’t because, more than anything, what really gives Argenta’s recording its winning edge is his peerless evocation of the sheer, spine-tingling “Spanish-ness” of the entire proceedings. After Argenta’s riotously abandoned coda, you may well be tempted to leap, applauding, from your armchair – I know I was (and, I confess, did).

This programme’s one piece of genuine Spanish music is Granados’s Andaluza, the fifth of his Danzas Españolas Op 37. This is a piano suite; as far as I can see, Granados didn’t orchestrate any of these dances, but several others did, though which one should have been credited here remains an unanswered question. Although I’m not au fait with the full set, this movement nevertheless sounds teasingly familiar. In the lilting opening, how elegantly Argenta moulds the music’s complicated-sounding rhythmic accompaniment, and yet how simple and sweet – and idiomatic – is the melody! In the middle, Granados seems to glance over his shoulder to an earlier age, before resuming the main material, now brimming not so much with “Spanish-ness” as the composer’s love of his homeland – a case of nationalism at its most exalted, all rendered most sympathetically by Argenta.

The España album is rounded off by Moszkowski’s Spanish Dances. That these are by some margin the least effective in idiom may be explained by the fact that Moszkowski was German; his idea of “Spanish” is more like, say, Massenet’s – so not even Argenta can winkle out of them a Spanish flavour on a par with Chabrier or Rimsky-Korsakov. Mind you, that by no means makes them “bad”; the composer deserves top marks for sheer entertainment value – there are lots of juicy tunes and springy, toe-tapping rhythms, brought to sparkling life by these immensely enjoyable performances.

Moszkowski’s Op 12 was written for piano (four hands); again, no orchestrator is credited. However, on the Web I fortuitously found the booklet note of Moszkowski: From Foreign Lands – Rediscovered Orchestral Works (Reference Recordings RR-138), which said, “Due to great public demand, the Spanish Dances Nos 2 and 5 were orchestrated in 1879 by his friend, Philipp Scharwenka (1847-1917), and Nos 1, 3 and 4 by Valentin Frank (1858-1929) in 1884.” This CD was published in 2014, and as far as I can tell, it is the only other recording of this orchestral version. I, for one, find that utterly incredible.

Now, what about that “filler”? This was a really neat idea. For one thing, a good half of Images obligingly continues the Spanish theme; and for another, “padding out” what would otherwise be a fairly curmudgeonly playing time (for a CD) with a single substantial work makes the issue doubly attractive. This beautifully recorded performance being in itself exceedingly attractive renders it a scrumptious icing on the cake.

A rather patchy Discogs page dates its first LP issue as 1957 (mono) and 1958 (stereo: in spite of the booklet claiming that Argenta’s Images was made in mono only), with LP reissue dates of 1967 and 1996 (the latter, a German issue, being “remastered”). The present disc seems to mark its very first appearance on CD – and on listening to it, I really do have to wonder why.

As you can see in the credits, both orchestra and venue differ from those of the España album. Many folk (far too many, if you ask me), summarily dismiss the Orchestre de la Suisse Romande of those days as a provincial second-rater – I presume by comparison with your average world-class, jet-setting, virtuoso orchestra. This is piffle. If the OSR didn’t have its fair share of plus-points, then how come so many of its recordings were – and often still are – considered so admirable? This Images, need I say, is one of them.

I have two critically commended recordings, both of which have secured places in my affections: Boston SO/Munch on a 1959 RCA Victrola LP (VICS 1162, now variously on CD, e.g. Sony G010003616346A), and the LSO/Previn digital recording originally issued on a 1979 HMV LP (ASD 3804) and 1983 EMI CD (CDC 7 47001 2). Listening to the three in succession, I was struck by how different they were, one from another. I reckon that this is largely due to Debussy having weaved into his marvellous score a plethora of musical strands that leaves conductors spoiled for choice.

Let’s see how they all fared with Gigues. The Munch sounds splendid, as indeed it should, being a 1959 Grammy Award-winning “Living Stereo” product. My only complaint was that Munch, as seems to be his habit, occasionally tended to push the quicker tempi a touch too hard. Otherwise, his view is bold, rhythmically alert, finely phrased and not short on atmosphere.

Previn’s recording – occupying the same historic slot in EMI’s digital canon as did Dutoit’s Daphnis et Chloë in Decca’s – inevitably sounds appreciably better, a veritable tapestry of luminous sound. I wonder, in what proportions are conductor and engineers to be credited with this sonic marvel? It feels that (although it probably isn’t so), they’ve elicited every single strand of the score. However, as most of them are merged into the background, you’d have to make an effort to “pull focus” on any particular one, so that in terms of evident detail Previn’s advantage over Munch is minimal. Previn’s tempi seemed more astutely judged, although overall perhaps a touch too reserved: he does not quite match Munch where “dancing” is concerned. On the other hand, Previn is the more atmospheric, if not by as much as you might imagine.

Now, what about the redoubtable Spaniard and his “dubious” OSR, whose recording is by a small margin the earliest of the three? Possibly with the help of Geneva’s Victoria Hall, this recording if anything is even more atmospheric than Previn’s. However, this is not at the cost of clarity: Argenta too elicits more detail than Munch – and, to the casual ear, in this respect gives Previn a run for his money, basically because he’s prepared to commit himself, “pulling out” lots of “plum” details – and making them tell.

A prime example is a striking “buzzing” phrase (tremolando sul ponticello, I think on violas, e.g. at about 2:26). Now, this fair pricked up my ears! I could have sworn that I’d never heard it before, and yet, when I checked carefully, it is indeed there in both Munch (also at 2:26) and Previn (at 2:41) – in both cases all-but-buried in the undergrowth, and rather more deeply in the Previn. Given the air that Argenta allows, it slots perfectly – and arrestingly – into the foreground argument. On top of that, Argenta is every bit as lively – and, where appropriate, “dancing” – as Munch, with the further advantage that he avoids any occasional rushes of blood.

To be even-handed, I feel that I should take a look at something static as well. I chose Parfums de la Nuit (in “Iberia”) – not only static, but also coming under the “España” umbrella. The timings are 8:20 (Munch), 10:15 (Previn) and 7:30 (Argenta); in other words, Munch takes 11% longer and Previn 37% longer than Argenta. In spite of the huge difference in timing, Munch feels far closer to Previn than to Argenta. Although the last is much the quickest of the three, he seems not in the least rushed – moreover, he sounds as though he’s inhabiting a different world (or at least “continent”).

Far from being somnolescent, his night is not just perfumed and sultry, but contains “things that go bump”. Soon after the start, Munch and Previn both put the solo oboe up-front, centre-stage, reducing all else to a distantly murmuring background. Argenta brings out, alongside – or even a bit in front of – that oboe, the gruff bass strings, which also slot perfectly into the foreground argument. If the playing sounds a bit coarse, you may well also wonder whether this was a patch of faulty playing; I did, at first, but soon became convinced that this was (as per “bump” and “gruff”) precisely what Argenta intended! Indeed, it must be said, as in the Chabrier and Rimsky-Korsakov, he imbues his entire Iberia with a real Spanish accent.

Yet, there’s more. Argenta had acquired Ansermet’s knack of drawing from the OSR playing imbued with an evident sense of affection, a wonderful warmth of expression that, to my way of thinking, transcends mere dexterity. Then again, Argenta’s performances ooze a very particular passion and excitement, giving us the best of the other two, plus a crucial something extra. What might that be? I’m not sure – but I am sure it’s there!

Am I perhaps overstating the case? Well, that’s for me to know and for you to find out – a most pleasurable course of action that I heartily recommend you take: “Legendary Performances” sums it up nicely.

Paul Serotsky

Help us financially by purchasing from