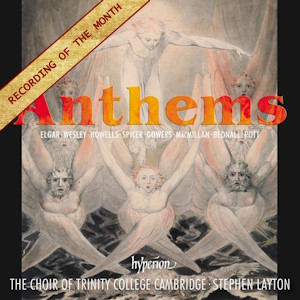

Anthems Volume 1

The Choir of Trinity College, Cambridge/Stephen Layton

Harrison Cole, Jonathan Lee (organ)

rec. 2022/23, Ely Cathedral, UK

Texts included

Hyperion CDA68434 [79]

By the time this review is published, Stephen Layton will have left his post as Director of Music at Trinity College, Cambridge. (Steven Grahl, Director of Music at Christ Church Cathedral, Oxford has been announced as his successor from January 2024.) Layton has held the Trinity post since 2006 but I believe he has decided now is the time to move on and concentrate on other conducting commitments. Part of the legacy he will leave is an extensive series of Hyperion recordings with the Trinity choir, of which this is the latest; its release coincides with him leaving the college.

The programme opens with Elgar’s Great is the Lord. By coincidence, earlier this year I took part in two concert performances of this anthem. It had been quite a number of years since I last sang it and I marvelled anew at how magnificent it is, not least in its word painting. It dates from 1910-12, when Elgar was at the height of his powers, as is manifest immediately in the commanding tune which the male voices proclaim. The Trinity choir sings the music superbly, alive to all the many contrasts of mood and dynamics in the writing. We also hear an excellent bass solo from Florian Störtz. Just as striking as the singing, though, is the organ playing of Harrison Cole. He exploits the resources of the organ in Ely Cathedral to its full, and he makes especially thrilling use of the reeds and of the pedal division.

Give unto the Lord is cut from the same cloth; Elgar wrote it for performance in St Pau’s Cathedral, London at the annual Festival of the Sons of the Clergy. In some ways, it’s even more dramatic than Great is the Lord, especially in its majestic opening pages. Just as noteworthy, though, is the tranquil central episode (‘in his temple doth ev’ryone speak of his glory’). There’s a truncated recapitulation of the opening music before Elgar ends the piece in a mood of tranquil assurance. This performance does full justice to every aspect of the piece.

Sandwiched between these two imposing Elgar pieces is The Wilderness by Samuel Sebastian Wesley. At first hearing, it may not seem as interesting as the Elgar works but Jeremy Dibble makes a persuasive case in his notes that the piece is advanced for its time, not least in its harmonic language. Wesley wrote it shortly after his appointment as Organist of Hereford Cathedral in 1832 and as I listened to this vivid performance two thoughts crossed my mind. One was to wonder what the people of provincial Hereford thought of this music by their new Organist. The other thought was whether at that time the cathedral had musicians capable of doing full justice to this music. In particular, the first half of this substantial anthem (13:44 in this performance) is sung exclusively by four soloists. The Trinity solo singers are first class and I can only presume that Wesley knew when he was composing the music that he too had at his disposal singers who would be up to the task. Layton and his choir give the piece an exciting performance, banishing completely any thoughts of Victorian cobwebs. Harrison Cole plays the important independent organ part splendidly.

Howells’ anthem The House of the Mind is, I think, less frequently heard than some of his other short choral works. That’s probably due to its difficulty. It dates from 1954, the same year as the fearsomely complex Missa Sabrinensis. In the anthem Howells set four verses of poetry by Joseph Beaumont (1616-1699), an Anglican clergyman and scholar who, unusually (I think), was successively Master of two Cambridge University colleges, Jesus and Peterhouse. Howells’ setting has its moments of typical full-throated ecstasy – during the second of the four stanzas, for example – but a good deal of the music is introspective, a mood which is emphasised by the composer’s habitual intensely chromatic harmonies. The Trinity singers and organist Jonathan Lee make a fine job of the piece.

Fittingly, the next piece is by a Howells pupil and biographer, Paul Spicer. Where the Howells piece often looks inward, Spicer’s Come out, Lazar is extrovert and intensely dramatic. It sets an anonymous medieval English text, telling of Christ’s miracle in raising Lazarus from the dead. Spicer’s exciting music conveys marvellously the momentousness of the miracle. The choir sing the music with commitment and great assurance while Jonathan Lee plays the challenging organ part magnificently.

Both organists are involved in the next piece because Patrick Gowers conceived Viri Galilaei for two SATB choirs and two organs! The first part of the anthem sets words from the Proper of the Mass for Ascension Day, telling of Christ’s Ascension into heaven. The piece begins mysteriously with heavenly ‘Alleluias’, as if from on high, and a hushed, awestruck narration. However, at ‘God is gone up with a merry noise’ the music becomes jubilant and increasingly complex. Eventually, Gowers sets a verse of the hymn ‘See the Conqueror mounts in triumph’. It’s a sturdy tune, which here is decorated by washes of festive organ figurations and cries of ‘Alleluia’ from all sides. You expect the piece to end on this note of triumph but Gowers has one more coup up his sleeve, ending the anthem, as it began, in hushed awe at the event which has taken place. Viri Galilaei only lasts for just over seven minutes but Gowers packs an awful lot into this short time span. It’s a thrilling, imaginative piece and it’s superbly performed here.

The opening pages of James MacMillan’s O give thanks unto the Lord set verses from Psalm 105 to music which is dynamic and urgently rhythmical. The central section is slower: here, MacMillan sets lines by Robert Herrick to music that is as beautiful as it is intense. Then the organ leads us back to the irregular rhythms and joyful dancing of the opening music.

Harrison Cole is at the console of Ely Cathedral’s organ for Toccata by Francis Pott. This is a super piece. There’s a short but thematically important introduction after which the toccata proper bursts forth. Pott uses intricacy in the articulation of the rhythms to make this a compelling and exciting piece. There’s a more relaxed, lyrical section in the middle before the toccata resumes, building to a tumultuous conclusion. Cole clearly has the measure of Pott’s music and he gives a scintillating account of this arresting piece.

To end, we have David Bednall’s setting of Siegfried Sassoon’s celebrated poem, Everyone sang. This was written for the wedding blessing of two professional singers. Jeremy Dibble tells us that many more singers were in the congregation so Bednall must have found irresistible the symbolism of Sassoon’s opening line, ‘Everyone suddenly burst out singing’ and, a little later, ‘Everyone’s voice was suddenly lifted’. Bednall sets both of those lines to suitably ecstatic music (requiring the sopranos to go up to top C in the process). But in a highly imaginative response to the words, he also includes a good deal of hushed, thoughtful music so that the piece, like Sassoon’s poem, is full of contrasts. I learned from the notes that right at the end, Bednall marks the music ‘Very slow – as if timeless’ and by this means his setting of the last few words, ‘the song was wordless, the singing will never be done’ is memorably apt.

This is a superb album. Stephen Layton has selected some thrilling pieces and his choir, which is on tremendous form throughout, sings them wonderfully. Their performances are alive to every nuance in the music and technically the singing is beyond reproach. A special word of praise is due to the two organ scholars, Harrison Cole and Jonathan Lee. All the pieces on this disc have critically important organ parts, several of them virtuoso in nature; between them they deliver thrilling performances, exploiting to the full the resources of the Ely Cathedral organ.

The performances are enhanced by the way that engineer David Hinitt and producer Adrian Peacock have effected the recording. The choir has great presence and clarity while the organ has been most excitingly captured.

As I said at the start, Stephen Layton has now relinquished his post at Trinity College, Cambridge. However, eagle-eyed readers will have noticed that this disc of anthems is designated as Volume 1: I understand that there are some more discs in the pipeline to follow this outstanding CD.

John Quinn

Help us financially by purchasing from

Contents

Sir Edward Elgar (1857-1934)

Great is the Lord, op.67 (1912)

Samuel Sebastian Wesley (1810-1876)

The Wilderness (1832)

Sir Edward Elgar

Give unto the Lord, op.74 (1914)

Herbert Howells (1892-1983)

The House of the Mind (1954)

Paul Spicer (b 1952)

Come out, Lazar (1984)

Patrick Gowers (1936-20140

Viri Galilaei (1987)

Sir James MacMillan (b 1959)

O give thanks unto the Lord (2016)

Francis Pott (b 1957)

Toccata (1991)

David Bednall (b 1979)

Everyone sang (2007)