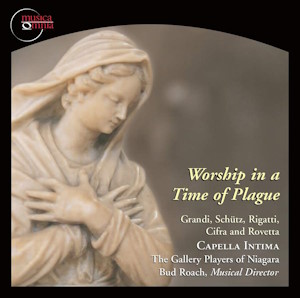

Worship in a Time of Plague

Capella Intima, The Gallery Players of Niagara/Bud Roach

rec. 2022 at the Central Presbyterian Church, Hamilton, ON, Canada

Texts only in translations

Reviewed as a stereo 16/44 download from Naxos

Musica Omnia MO0804 [61]

If one looks at the years of death of Italian composers from the first decades of the 17th century, the years 1630 and 1631 are mentioned several times. It was the time that northern Italy, and in particular the Veneto, was struck by the plague. Alessandro Grandi and Giovanni Paolo Cima among those who are known to have died of the plague, in Bergamo and Milan respectively. Other possible victims were Giovanni Battista Fontana and Dario Castello. On 22 October 1630 the Doge Nicolò Cantarini decided to dedicate a church to the Virgin Mary should the city be freed from the plague. He did not live long enough to see that happening, as he himself became one of the epidemic’s victims. Due to financial problems, the Santa Maria della Salute was consecrated as late as 1687.

However, on 21 November 1631 the first service of thanksgiving was held, which was repeated every year since. Part of the Festa della Salute was a procession to the location where the church of Santa Maria della Salute should arise. Obviously music was an integral part of the festivities, but although it is documented that Monteverdi composed a mass to be performed at St Mark’s, nothing is known for sure about what was actually performed. The ensemble ecco la musica put together a programme of music that was written around the years the plague took place (Christophorus, 2021). Bud Roach also took the plague as the starting point of his recording, but does not specifically refer to the Festa della Salute. An important thread is the music of Heinrich Schütz, who stayed in Venice in 1628/29, and left just before the plague hit the city.

“We have assembled a selection of music to which Schütz would have been introduced in 1629, including offerings from his volume of Latin motets composed and published during his stay, as well as examples from the plague years in which music publishing had come to an almost complete standstill.” Rather than performing music that is well-known, such as pieces by Claudio Monteverdi, the ensemble focuses on lesser-known repertoire. That includes sacred concertos from Schütz’s Symphoniae Sacrae I, which were published in Venice in 1629. That collection has been recorded a number of times, and therefore one can hardly claim that they are little-known. However, this disc seems to be aimed at the North-American market in the first place, and there Schütz may be not that well-known.

The selection of pieces seems not to have been inspired by the plague. I can’t see any connection between the texts and the tragic events of the years 1630/31. “The motets recorded here, although most of them pre-dating the plague of 1630 by a year or more, still represent the music of the plague years. In the absence of new music for worship, these collections of motets would have taken on a new meaning for both performers and congregants: a new perspective of remembrance and urgency.” The liner-notes also refer to our time, the COVID-19 pandemic and its effects, just like the Christophorus disc was inspired by this event. “Our own recent experiences have not been as ruthlessly cruel as Early Modern plague, but we are able to appreciate the circumstances of the Venetians with some sense of familiarity. We share, as they must have done, a feeling of seeking solace and hope in times of isolation and uncertainty, just as we also find comfort in music as our expression of faith.”

Schütz’s Symphoniae Sacrae are an impressive testimony of what he had learnt in Italy. During his formative years he had studied with Giovanni Gabrieli, one of the last representatives of the stile antico. Although in Gabrieli’s latest works we find some traces of the new style, the seconda pratica, it was his teaching of counterpoint that was Schütz’s inspiration all his life. In his Geistliche Chor-Music of 1648 he proclaims that counterpoint is the foundation of all music. However, he was always open to the new style, and in order to listen himself to what was written there by Monteverdi and others, he asked and was given permission to go to Venice. Six pieces from the 1629 collection are included here, scored for one to three voices, two violins and basso continuo. They show how he had internalized the declamatory style of the Italian monody. Four concertos are pairs: O quam tu pulchra es / Veni de Libano and Benedicam Domino in omni tempore / Exquisivi Dominum. Unfortunately there is too much space between the first and second parts, which nullifies their connection. In the case of the former pair – whose texts are taken from the Song of Songs – the connection is emphasized by the frequent repetition of the opening lines: “O quam tu pulchra es” in both of them, as a kind of ritornello.

This was a very common device, and one finds it in many compositions of this period, for instance in Alessandro Grandi’s O beate Benedicte, a piece for St Benedict, and in Bone Jesu verbum patris. Grandi was one of the most brilliant composers of small-scale sacred concertos of his time. The three pieces included here attest to that. Schütz knew them, and in his Symphoniae Sacrae III of 1650 he included an arrangement of one of Grandi’s sacred concertos.

The programme also includes some items in which the two styles of the time are mixed, just as we find it in Monteverdi’s oeuvre, for instance in the psalms of his Vespers of 1610. It means that episodes for a full ensemble alternate with passages in declamatory style for one or several solo voices. These pieces are from the pen of Giovanni Rovetta and Giovanni Antonio Rigatti as well as of two composers who did not work in Venice: Stefano Bernardi and Antonio Cifra.

Rovetta was born in the city and may have been a choirboy at St Mark’s, although there is no documentary evidence for that. However, his father played the violin in the cappella of St Mark’s between 1614 and 1641. Giovanni also first appeared as a player in the cappella in 1614. Until the end of his life he was connected in one way or another with this church. In 1623 he was appointed a bass singer and in 1627 he succeeded Alessandro Grandi as assistant maestro di cappella to Claudio Monteverdi, whom he succeeded after the latter’s death in 1643. Laudate pueri is one of the Psalms for Vespers.

Rigatti was born in Venice, became a choirboy at St Mark’s in 1621 and was educated for a career in the church. From 1635 to 1637 he acted as maestro di cappella of Udine Cathedral. His salary was twice that of his predecessor, which says something about his status. In 1639 he started teaching at the Ospedale dei Mendicanti and later also the Ospedale degli Incurabili. At the end of his life he became sottocanonico of St Mark’s, but he died only after about fifteen months in office. Credidi, propter quod locutus sum is a setting of Psalm 115.

Bernardi was from Verona, where he also worked for some time, as well as in Rome. In 1627 at the latest he was appointed Kapellmeister at Salzburg Cathedral. Dixit Dominus is one of the Vesper Psalms. Here Bernardi does not forget to illustrate the most dramatic verses in the second half. Antonio Cifra started his career in Rome and then went to Loreto, near the Adriatic coast, where he spent the rest of his life. Angelus ad pastores ait is a piece for Christmastide, and is a bit of an odd choice for this programme.

Like I said, Schütz is not unknown to many music lovers, but even if one knows his music rather well, it is interesting to hear his Symphoniae Sacrae of 1629 being put into a framework of Italian music of the same time, which attests to the stylistic similarity between the German and his Italian contemporaries. The inclusion of pieces by Grandi is also very welcome, as he still does not receive the attention he deserves. The three concertos performed here are brilliant examples of his art.

As far as the performances are concerned, there is certainly much to enjoy here. The Capella Intima is a fine ensemble which includes singers who show here their stylistic insights. The voices blend well, although the two baritones use a little too much vibrato. Grandi’s In te Domine speravi, which is a duet for two basses, suffers especially from that. Sometimes I found the tempi a little slowish, for instance in Schütz’s Exultavit cor meum. It is a jubilant piece, and that does not quite come off. Two issues regard the entire recording. The singers could have added more ornamentation. There is always the danger of overdoing things, and especially Schütz requires some restraint in this department. However, in the Italian pieces a little more of it would have been appropriate. And then there is the issue of dynamics. There should have been more and stronger dynamic contrasts, both in the vocal and in the instrumental parts. The messa di voce was an important tool of singers and players, and that is something I have missed here.

On an editiorial note: the booklet includes informative linrer-notes, but unfortunately the lyrics are only available in translations. The omission of the original lyrics makes it hard to observe the connection between text and music.

Johan van Veen

www.musica-dei-donum.org

twitter.com/johanvanveen

Help us financially by purchasing from

Contents

Giovanni Rovetta (1596-1668)

Laudate pueri

Heinrich Schütz (1585-1672)

Paratum cor meum (SWV 257)

Alessandro Grandi (1586-1630)

In te Domine speravi

Bone Jesu verbum patris

Stefano Bernardi (1580-1637)

Dixit Dominus

Heinrich Schütz

O quam tu pulchra es (SWV 265)

Veni de Libano (SWV 266)

Giovanni Antonio Rigatti (1613-1638)

Credidi, propter quod locutus sum

Heinrich Schütz

Benedicam Domino in omni tempore (SWV 267)

Exquisivi Dominum (SWV 268)

Alessandro Grandi

O beate Benedicte

Heinrich Schütz

Exultavit cor meum (SWV 258)

Antonio Cifra (1584-1629)

Angelus ad pastores ait