Nikos Skalkottas (1904-1949)

Concerto for Violin and Orchestra A/K 22 (1937/38)

(New critical Edition ed. Dr. Eva Mantzourani)

Concerto for Violin, Viola and Wind Orchestra A/K 25 (?1939-40)

(First Critical Edition ed. Dr. George Zacharias)

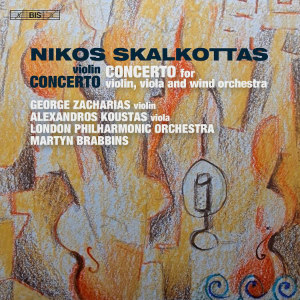

George Zacharias (violin), Alexandros Koustos (viola)

London Philharmonic Orchestra/Martyn Brabbins

rec. 2020/22, Henry Wood Hall, London

BIS BIS-2554 SACD [58]

An earlier notice of this album used the term “abrasive” of the Double Concerto for Violin, Viola and Wind Orchestra. Are wind bands so aptly described? Well, they can be physically assertive, up-and-at your ears and your physiognomy, but they can also be songful, mellow, smoky and jazzy and noirish. That late-night thing. Are night clubs abrasive? I guess it depends on how much you drink, what this does to your mood and the company you keep.

Whatever the free associations, Skalkottas’ Double Concerto easily embraces the moodswings of that gamut, and the present World Premiere (yet another one – exciting times for the Happy Band of Skalkotts!) is extraordinary, one of our composer’s most compelling and exciting late-30s inspirations, when, similarly to Bartok, Skalkottas was blending his rigorously individualised post-Second-Viennese techniques with a catchy, folksong-and-dance popular style developed in his marvellous 36 Greek Dances.

It should have “caught on” by now shouldn’t it? This Skalkottas thing? Lack of touring by Greek orchestras, perhaps? No-one playing selections from those 36 Greek Dances as a Proms encore or two…? Make a change from Brahms à la hongroise, wouldn’t it? So Nikos remains the secret pleasure of a happy few, outside Greece at least. Let’s hope Naxos also continue their excellent series. Two albums are not enough!

The slow movement finds Skalkottas at his most Weillian and overhung, midnight-movie-idiomatic for brass and winds, brooding dark thoughts in the eve-of-war gloom, a music he must have heard often when in Berlin, studying with Schoenberg – with whom he fell out over his own use of multiple tonerows, his own idiosyncratic adoptions of serialism. We can only be grateful he did, given the intensity, concision and rhythmically and melodiously inventive inspirations that resulted, especially from the late 1930s on – mostly for his bottom-drawer back in Greece, scraping a living in the back desks of various orchestral violins. (Bottom-drawer creativity is intriguing isn’t it? Devil-may-care freedom to dare, to imagine and to invent marvels of the inner world – but at the expense of performance-impracticability? Subject for another essay.)

Back to the start – in the first movement you think, ah, the typical later-Skalkottian barging-about on the dancefloor, the pushy, assertive folk-rhythms as the exposition gets under way (thematically close to the equally compelling Concerto for Two Violins) – but the syncopations are always gripping (and explosively punctuated), and soon songfulness returns in an equally typical suave second subject for solo winds of various colours. Then the soloists arrive to elaborate upon it all, Skalkottas keeping faith, as usual, with his devotion to quite strict classical sonata-concerto form. His flowingly continuous forms can seem hard to follow – there are few, if any, pauses – but if one keeps the classical shapes in mind repeated hearings and familiarity should do the rest. There are some lovely moments as the development and the very varied recap flow seamlessly through to the coda; the trumpets’ spiking of the soloists intertwined song is especially witty in its contrasts. Into the smoky dive of the andantino those brooding brasses set the urban scene; our virtuosos prop up the bar with dark reflections, deftly switching roles between song and accompaniment, then duetting in elaborate melismas. There’s always time for one more vodka shot isn’t there?

The finale is like a freer more concise variation of the first movement sonata (cf. Bartok Violin Concerto No. 2; recall too, that Skalkottas’ own Violin Concerto was planned as a three-section sonata form) but with wilder fanfares and more relaxed singing soloistic lines; listen closely, and you should pick up the thematic parallels, the second subjects especially. A crash, a sudden leap in pace and night is over; we made too much noise and got thrown out clutching our bottles.

What a great piece; of the Concertos, only the one for two violins, left in a two-piano arrangement, orchestrated by Kostis Demertzis, is as catchy, memorably folk-pop in its musical cultures, yet sacrifices no musical complexity. If only our guy had been given more than 45 years to offer us further pleasures.

The Violin Concerto itself, composed just a year earlier but stylistically very different, may seem studiedly, seriously the post-Schoenbergian serialist alongside those barging, ruminative bar-room brasses. But the sinuous irregular opening melodies, the nocturnal con moto, the swinging, hipswaying theme of the finale and its jaunty second group, soon reel the listener in, seeking poetry – or at least pleasure – among the systematics.

This new release presents it in a recent critical edition, Zacharias basing his performance score on the presentation edited and extensively corrected and annotated by Eva Mantzourani (premiered in Athens in 2019). No details are given of how it differs from the previous BIS recording but many differences are perceivable, especially the shorter timescale for the andante. There is a striking contrast in the performances, though, and here, the new Zacharias/Brabbins scores over the earlier Demertzis/Christodolou in its tighter grip and expressiveness of the musical line and architecture. It does this by being far quicker in the andante, but slower in the finale – where Brabbins brings out the swing, when those winds come out for their jaunt, before the violin re-enters. The SACD sound is also richer and fuller on the newcomer, the warmly distinctive character of Zacharias’ Seraphim violin beautifully, distinctively caught. So BIS-1 feels more like a study-score in performance, BIS-2 a vivid interpretation, emphasising the (largely unsupplied) need for alternative Skalkottian uptakes.

Skalkottians will of course need both.

If you haven’t yet got the bug, I’d recommend both this album, and the earlier BIS issue with the Concerto for Two Violins (BIS CD-1554) as good entry points; perhaps even more so, the two Naxos releases (8.574182 and 8. 574154). The first of these has the only extant recording of the intense, growlingly dramatic and wide-ranging Suite No.1 (1929/35), a truly extraordinary creation to astonish even the well-seasoned ear. Imagine the Symphonies that might have followed it had Skalkottas even lived to a mere 60…would Schoenberg have said that, like Sibelius and Shostakovich, his former pupil also had “the breath of symphonists”?

Jayne Lee Wilson

Previous review: Gary Higginson (April 2023)

Help us financially by purchasing from