Déjà Review: this review was first published in August 2003 and the recording is still available.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791)

Violin Concerto No. 3 in G major, K216 (1775)

Bassoon Concerto in B flat major, K191 (1774)

Jan Václav Hugo Voříšek (1791-1825)

Symphony in D minor, Op. 24 (1820-21)

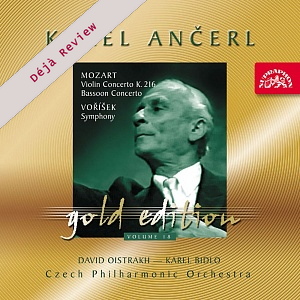

David Oistrakh (violin), Karel Bidlo (bassoon), Czech Philharmonic Orchestra/Karel Ančerl

rec. December 1950 (Vorisek), February 1952 (K191), April 1954 (K216), Rudolfinum Studio, Prague

Ančerl Gold Edition Volume 18

Supraphon SU3678-2 [71]

Karel Ančerl was poised for a wonderful career as a conductor when World War II sent him on a detour to Terezín and Auschwitz where he managed to survive but lost his family. After the war he continued to conduct, but his rise to fame didn’t begin until he was appointed the artistic director of the Czech Philharmonic Orchestra in 1950. Ančerl took his orchestra to the heights of international acclaim for a period of 18 years at which time he decided to emigrate because of the events of 1968. He then became Chief Conductor of the Toronto Symphony Orchestra, and North America gained one of the greatest conductors of the 20th Century.

The Karl Ančerl “Gold Edition” consists of 42 volumes, of which the present disc is Volume 18. The performances are of previously released material that has been remastered and now sounds less shrill and wider in dimension than on earlier transfers.

Mozart needs no introduction, but Voříšek is now a relatively obscure composer who practised his art during the transitional period between the Classical and Romantic eras. Born in Bohemia the same year that Mozart died, Voříšek also had the same life span. He came from a musical family and went to the University of Prague in 1810. However, Vienna was the best spot for a composer at that time, and Voříšek joined many other Bohemian composers in 1813 in this great cultural enclave. He enjoyed an excellent career in Vienna as a conductor and keyboard performer. Most recordings of his music are devoted to his solo keyboard works, but there have been a few recordings over the years of his four-movement Symphony in D minor.

Although Voříšek has sometimes been linked musically to Mozart and Haydn, his Symphony in D minor clearly looks toward Beethoven for inspiration in its power, angst, and sudden turns in emotional content. This is not a masterpiece for the ages, but an exceptionally well crafted symphony with a fine mix of poignancy and high drama.

There have been two recordings of recent vintage of the Symphony in D minor. One is from Sir Charles Mackerras on Hyperion, while the other is from Paul Freeman on Cédille. The Mackerras, although finely played, tends to look backward to Mozart. Freeman’s performance is superior as it fully conveys Beethoven’s influence and is more dramatic with more punch than the Mackerras.

Ančerl’s interpretation is very much in spirit with Freeman’s. I don’t want to knock Freeman at all, because his performance of the Symphony is excellent in all respects. However, he just can’t measure up to Ančerl who gives the three “Allegro” movements greater tension and abandon. Particularly stunning is the Trio of the 3rd Movement Scherzo where Ančerl takes a simple pastoral scene and lifts it into a spiritual quest. Freeman only offers the simple pastoral scene.

The 2nd Movement Andante also shows Ančerl to be in command. The music has a mix of yearning and quiet satisfaction that Ančerl stretches through a slower tempo than used by Freeman. The way Ančerl gets his strings to incisively lengthen the most poignant moments is especially compelling, and his entire interpretation and execution of the Symphony in D minor is outstanding.

Mozart’s Violin Concerto in G major has received many superb past recordings, and Ančerl’s is right up there with the best. Partnered by the legendary David Oistrakh, the performance is on the rugged and serious side with Oistrakh giving a relatively sharp and sinewy interpretation. In contrast, the exceptional Stern/Szell performance is rich and very optimistic in presentation with Stern displaying a sweet and full violin sound. The 3rd Movement Rondo finds Ančerl and Oistrakh giving scintillating interpretations; the excitement Oistrakh creates with his sharply phrased and energized lines is magnificent and worth the price of the disc on its own.

In Mozart’s Bassoon Concerto, Ančerl’s outer movements are more sharply etched than Abbado’s, and Ančerl generates significantly more tension. However, Karel Bidlo can’t match the dual qualities of melancholy and optimism possessed by Willard Elliot in the 2ndmovement Andante that is one of my favorite Mozart creations. I am very particular about the bassoon part of this movement and think that Elliot’s limpid tones are spiritually uplifting. Overall let’s call it draw, because both versions of the Bassoon Concerto are exceptional.

In conclusion, over 70 minutes of great music-making is what you get with this superb Karel Ančerl volume of his “Gold Series”. The only question is whether those who already own previous transfers of the performances will derive net benefits from plunking down the cash for the disc. I can’t answer that question definitively, preferences in sound being so personal in nature. What I can assure readers is that the remastered sound has a bloom largely missing in past reincarnations that gives the performances an added dimension. This isn’t a major bloom, but I can notice it. Dedicated Ančerl enthusiasts will want the new recording, and I am pleased as punch to have a copy of my own.

Don Satz

Help us financially by purchasing from