Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791)

Symphony No. 39 in E flat major K543

Symphony No. 40 in G minor K550

Symphony No. 41 in C major K551 ‘Jupiter’

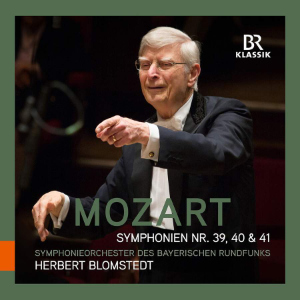

Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra/Herbert Blomstedt

rec. live, 17-21 December 2019, Philharmonie im Gasteig (39); 31 January – 1 February 2013, (40); 18-22 December 2017, Herkulessaal der Residenz (41), Munich

Reviewed as a digital download from a press preview

BR Klassik 900196 [2 CDs: 102]

The renowned American-born Swedish conductor Herbert Blomstedt has just celebrated his ninety-sixth birthday which marks his sixty-nine years as a conductor, having made his debut with the Royal Stockholm Philharmonic Orchestra in 1954. Blomstedt has been a close partner of the BRSO and a regular guest conductor.

My experience of Blomstedt performances has been limited to attending and reviewing a couple of his concerts. In 2017 I reviewed Blomstedt’s ‘inspirationally intense and exceptional performance’ of J.S. Bach’s ‘Johannes-Passion’ with the BRSO in the Herkulessaal, Munich. As recently as May 2023 I reported from a Blomstedt concert at Kulturpalast, Dresden with the Chamber Orchestra of Europe where the frail looking conductor drew a standing ovation for his conducting of Mendelssohn’s violin concerto (soloist María Dueñas) and Symphony No. 3 ‘Scottish’.

As recently as 2018 the BR Klassik label released a single album with Blomstedt conducting the BRSO comprising of the Symphonies No. 40 and No. 41 ‘Jupiter’ recorded live at Herkulessaal in 2013 and 2017 but they have here created a double album by re-releasing the same two live recordings and adding Blomstedt’s live performance of the Symphony No. 39 with the same orchestra and recorded in 2019 at the Philharmonie.

This recording reminds me of attending the 2012 Dresden Music Festival in the Semperoper when I reviewed a performance of these final three symphonies played by the visiting Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Daniel Barenboim. Prior to that concert, I recall wondering if the programme would prove to be too much of a good thing. My fears were entirely unfounded as I witnessed a majestic concert under Barenboim that showed these symphonic masterpieces in the best possible light. Something very special had occurred.

Unique works, Mozart’s final three symphonies have an enduring popularity with orchestras and audiences alike. During the summer of 1788 in Vienna, Mozart was experiencing many challenging events in his private life, including straitened circumstances, declining popularity and the death of his daughter. In marked contrast to these personal difficulties, he embarked upon an incredibly fertile burst of activity, rediscovered his appetite for symphonic writing and began to focus on his final three symphonies, each having distinct contrasts of sound and atmosphere. These are pioneering works of model craftsmanship, strong individual expression, intensified dissonance, and broad dynamics. The previous scholarly consensus had the thirty-two-year-old Mozart completing his final three symphonies in quick succession, all written within a time frame of some six weeks, but more recent research suggests that they probably had a much longer gestation period.

The Symphony No. 39 in E flat major, K543 is a grand and festive work where the instrumentation – unusually for Mozart – doesn’t use oboes, calling instead for flute, pairs of clarinets, bassoons, horns, trumpets with timpani and strings. For a work written when Mozart was in the pit of despair, it’s actually infused with many aspects of the dance. The opening movement is the predominantly dance-like in character, the Trio of the third movement is a traditional Austrian Ländler the finale has a spirited, Haydnesque contredanse. Blomstedt conducts a sincere and warm reading and I particularly enjoyed the Andante con moto where he creates an engaging sense of peace and tranquillity. Successful, too, is the Menuetto. Allegretto – Trio in which Blomstedt accents the cheerful and uplifting dance elements, redolent of elegant ballrooms at the Viennese court.

There are two versions of the Symphony No. 40 in G minor, K550, originally scored for flute, pairs of oboes, bassoons and horns with strings but without clarinets, trumpets and kettledrums. The revised version customarily performed today has a pair of clarinets added with revision of the oboe parts. Markedly, neither score calls for trumpets and timpani. Blomstedt has stated how Mozart had ‘placed all the dark sides of human existence into his G minor Symphony’. Of the triptych, I think this Blomstedt performance of No. 40 is superior for its greater impact. My view is that the perceived doom and gloom of the work are somewhat overstated although of course there are uneasy aspects in the score. Blomstedt provides a pleasing contrast between the passages that communicate anxiety and storm with those of brightness and geniality. Standing out is the Andante with its warm and delightful writing, variegated with dusky, uneasy episodes. In the finale marked Molto assai, one of the most volatile movements Mozart ever wrote, the playing of the Bavarians is compelling.

Mozart’s No. 41 in C major, K551 has the nickname ‘Jupiter’, most likely a title allocated by impresario Johann Peter Saloman around thirty years after its completion. Mozart’s scoring is for flute, pairs of oboes, bassoons, horns, trumpets with timpani, strings but noticeably no clarinets are used. Over the centuries many vibrant adjectives and superlatives have been used to describe this majestic work the longest in duration and the most complex, too, with a strong emotional content. In the finale marked Molto allegro, the remarkable contrapuntal display in the memorable and widely celebrated coda stands out for me. Mozart biographer Hugh Ottoway described the Jupiter as ‘one of the marvels of Classical music.’ In the opening movement Allegro vivace, the clarity of the trumpet and drums evokes a martial pomp. Under Blomstedt this is noble, rather extrovert music with short, lighter passages of considerable charm. Although attractive the surface calm in the lyrical Andante cantabile reveals a sombre vein. Foot-tapping and lively, the catchy Ländler-like rhythms of the Menuetto marked Allegretto take on a Haydnesque quality. Entirely engaging, in Blomstedt’s hands the urgently vivacious concluding movement Molto allegro is full of merry celebration of a festive occasion. Bold and uplifting, the magnificent fugal coda for full orchestra where all five themes are combined has a remarkable whirling energy.

The dignified Blomstedt eschews theatrics, adopting a calm controlled approach. His choice of pacing is astute, and his range of dynamics is wide. The Bavarian orchestra will know this music inside out and it shows. In these live performances the playing is not flawlessly accurate and unified yet it’s more than acceptable and certainly characterful. The string section has toned down the level of vibrato and the glowing brass and colourful woodwind tone are admirable. The Bayerischer Rundfunk (Bavarian Broadcasting) excels, providing clear, well-balanced sound quality. Jörg Handstein’s booklet essay “The Big Three – Mozart’s Last Symphonies” is interesting and informative.

I have three benchmark recordings. The first is ‘big-band’ Mozart, the outstanding now ‘classic’ accounts from the Berliner Philharmoniker under Austrian conductor Karl Böhm. Recorded under studio conditions in 1961-62 at Jesus-Christus-Kirche, Berlin, this double set is on Deutsche Grammophon reissued and remastered on its ‘Legendary Recordings – The originals’ (c/w Symphonies 35, 36 ‘Linz’ & 38 ‘Prague’). If I’m in the mood for harder driven performances, I turn to the live recordings that American conductor Leonard Bernstein made with the Vienna Philharmonic. Bernstein recorded these markedly dramatic accounts in 1981-84 at the Goldener Saal, Musikverein in Vienna on Deutsche Grammophon. My choice for a period instrument recording has altered from Marc Minkowski conducting Les Musiciens du Louvre to the most persuasive accounts by Dutch early music specialist Frans Brüggen conducting the Orchestra of the 18th Century. At the forefront of period instrument performance practice, his accounts of the late triptych were recorded live in 1985-1988. My recordings form part of Brüggen’s eleven CD box set, a highly recommendable collection of all-Mozart works on Decca. In the same Decca box there is a later, second Brüggen recording of the G minor symphony from 1991.

Blomstedt and BRSO play extremely well; nevertheless, I don’t feel that their partnership quite reaches the heart of these late Mozart symphonies nor does it achieve the same level of vitality and focus of my three benchmark recordings.

Michael Cookson

Previous reviews: David McDade (June 2023) ~ Ralph Moore (May 2023)

Help us financially by purchasing from