Déjà Review: this review was first published in August 2001 and the recording is still available.

Gustav Mahler (1860-1911)

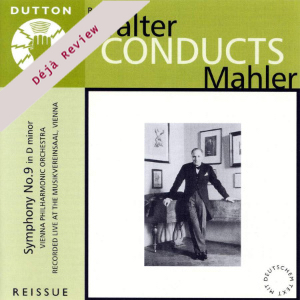

Symphony No. 9 in D Minor

Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra/Bruno Walter

rec. “live”, 16 January 1938, Vienna

Dutton CDBP9708 [70]

Anyone interested in the history of this symphony needs to have at least one version of this “live” 1938 recording by the Vienna Philharmonic conducted by Bruno Walter; so different, and therefore so illuminating, from his later stereo remake in California in 1961.

Over and above any details of playing and interpretation this is a document of a unique occasion too. Eight weeks after this performance took place Austria became part of Hitler’s Third Reich. Remember that when you sense the presence of the audience and what must have been on their minds – fear or anticipation, depending on their political viewpoint. Walter fled westward after this performance and many of the players in the orchestra would not be in their places when concerts resumed after the war, so here is the end of an era commemorated by the performance of a work that was itself commemorating the end of another.

There is a moment in the first movement 27 bars from the end when the whole orchestra is silent but for the solo flute descending and you can nearly touch the atmosphere in the hall. It is aspects like these that give recordings like this their unique quality; one clearly recognised by Walter himself when producer Fred Gaisberg played him test pressings in Paris a few weeks later. There were tears in the delighted conductor’s eyes as he gave Fred Gaisberg the clearance to release the recording commercially.

So far there are four CD versions of the recording available and a fifth rumoured to be due. Only the one from EMI is taken from original matrices as all the others come from commercial pressings and offer a variety of approaches from the remastering engineers. This version is a straight reissue by Dutton Laboratories of their fine 1996 version but importantly it results in a new super bargain price and that is always to be welcomed.

The performance itself is unique and unforgettable and will be known to many Mahlerites already. However, there are always new converts to the cause who need to know why it is held so dear by so many. Tempo-wise the first movement seems to me to be near ideal though many accustomed to the more indulgent, more apparently moulded, approach to Mahler that has taken over in the last twenty or thirty years might disagree. That is not to say Walter doesn’t mould the music. He does, it’s just that the tempo in which he does it is quicker overall than that we have become used to. This is walking pace with a singing line that seems as though it’s taken in one breath and sung. The strings of the old pre-war Vienna Philharmonic also ache with nostalgia and seem to have the flexibility of the human voice as Walter leads them into his interpretation. But there is also a more restless and cumulatively unsettling mood that really only becomes apparent by the end. You can forget the moments of imbalance in the sound level or the limited sonic generally. Or at least you should if music means more to you than sound.

The second movement is a true rustic Ländler, harsh and stomping, almost “cheap”, reminding us that those conductors and orchestras who “prettify” Mahler, smooth his sharp edges off, do him no favours at all. Hear the bows dig into the strings like village fiddlers at some Upper Austrian hop. It isn’t rushed either, as it so often is. Contemporary conductors of this work should really be made to sit down and hear it before they arrive on their podiums. By the arrival of the Rondo Burleske third movement, it must be admitted, the strain is beginning to tell on the VPO. In one sense this is no bad thing as it adds to the feeling of a world going smash, which it was about to do outside the concert hall in the same way as it did a few years after Mahler wrote the symphony. The orchestra, who can’t have played this all that often, hang on for dear life but this only adds to the tension, the feeling of the concert hall as theatre. Are they going to make it? Yes, but it’s a close-run thing. You really wouldn’t want to hear this too often but then this is not a reference version as the fluffs and imprecision can irritate even me at times. But hold it against some of the “squeaky-clean” digital studio versions of latter years and it just demands its place in the profile of recordings.

In some ways the Adagio last movement is a bit of a disappointment even for an admirer of this performance like me. It is certainly the quickest you’ll hear in overall tempo. The coda especially seems to flash by when held against Bernstein, Haitink, Horenstein and others. The first time I ever heard it (on the old World Record Club LP issue) I had to follow with a score to convince myself that nothing had been cut out. Nothing has, of course. Again it’s just different from what you may be used to. It certainly seems to work in the context of the rest and the strings are just as glorious here as they were at the start, listened to through the ageing sonics, of course. I have often wondered whether Walter sensed that the audience were maybe losing concentration towards the end and hurried a little more than he might have done.

The recording was produced in the era before tape recordings by having two cutting styli running in relay. A non-playing member of the orchestra sat next to the engineer with a score so the gain control could be taken up and down to guard against distortion with a man in view behind the orchestra to signal when to switch on the current. This version from Dutton and the one from EMI (CDH 7 63029 2) are perhaps the most easily available so a short comparison is in order. Overall I found that whereas with the EMI my “seat” is in the gallery somewhere near the back, the Dutton has me in the stalls nearer the front. By that I mean the Dutton is closer and more detailed, the EMI more distant and less well defined. In the Dutton the strands of the score are more apparent and instruments are plainer, especially solos. Telling examples are the rasp of horns and the flutter of flutes and in the EMI these were less obvious. It has to do with the fact that in Dutton the higher frequencies appear enhanced and lower frequencies decreased with greater definition right across. This may have to do with the Cedar process used. So, where in EMI the timpani seemed to underpin, in the Dutton they are more contained and come from one part of the sound picture.

So the Dutton is the one to have, you might think? Answering that is where it starts to get problematic. The gain in detail in the Dutton is certainly welcome. One problem, though, is that you also get detail you might not want. The violins do sound a little harder in the Dutton and the lessening of the bass end makes them less resonant which is something I have always liked in the EMI. This lessening of resonance also marries to a lessening of reverberation. So, with the aural picture closer, the whole experience is less comfortable in Dutton, at least for these ears. There is also more of the audience to be heard. They are not a bad audience but what few coughs there are come across with more clarity (as does the foot stamp by Walter at the start of the scherzo and, what Dutton has now convinced me, a string breaking about three minutes into that same movement). If you have the EMI and are happy with it, my advice is to stay with it. If you do not have the EMI but want this important recording in one form or another, my advice is to sample both if you can. In spite of the fact that the Dutton has all the virtues over the EMI that I have outlined, I could easily imagine people preferring the EMI for its “easier on the ear” feel. However, Dutton now offers the recording at super bargain price and that must count a great deal.

There is no excuse for not owing this famous recording with so much resonance, musical and historical.

Tony Duggan

Help us financially by purchasing from