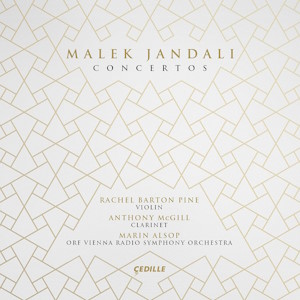

Malek Jandali (b. 1972)

Concerto for Violin and Orchestra (2014)

Concerto for Clarinet and Orchestra (2021)

Rachel Barton Pine (violin)

Anthony McGill (clarinet)

ORF Vienna Radio Symphony Orchestra/Marin Alsop

rec. 2022, Funkhaus Wien Grosser Sendesaal, Vienna

Premiere Recordings

Cedille CDR90000220 [61]

These two concertos by Malek Jandali are full of varied colours and textures, while being relatively conventional in structure. The harmonic language is largely what one might call modern orthodox, though occasionally complicated by the use of middle-eastern instruments and musical patterns. Both works are, however, both intriguing and eminently approachable.

The music of Jandali is inseparable from his origins and their consequences. He was born in Homs, a city in Western Syria which has sometimes been described as the ‘capital of the Syrian revolution’ given its early and strong opposition to the Assad government. Jandali studied at the Higher Institute of Music in Damascus before winning a scholarship which enabled him to attend North Carolina Schol of the Arts in the USA. He graduated from Queens University in Charlotte, North Carolina, his work as a pianist gaining him the institution’s Award for Outstanding Musical Performer. He is based in the USA and has given performances across North America and beyond – including in such cities as Cairo, Paris, Istanbul, Vienna, Madrid, London and Dubai.

Naturally Jandali has felt very strongly the sufferings of so many of Syria’s inhabitants in the still continuing civil war and has been active, both in his music and outside it, in support of the people of his homeland. Such matters were made very personal to Jandali when, in 2011, he accompanied the singer Salma Haddad in a performance of his song ‘Watami Ana’ [I am my homeland] during a peaceful demonstration in Washington D.C.; within a few days Syrian security forces attacked his parents’ home in Syria, beating both his parents brutally and laying waste to their house.

As an activist, Jandali has given many talks and played many benefit concerts for a range of humanitarian causes, not just with reference to Syria. So, for example, in Atlanta he founded Pianos for Peace (for which Marin Alsop is an ambassador), a charity which seeks to bring “the arts and peace to people and communities in need” (quoted from the Pianos for Peace website).

The same attitudes and principles are at work in much of the music he has written, which typically incorporates Middle Eastern and specifically Syrian elements within Western musical structures. It is important to stress, however, that such non-Western elements are not used as decorative exotica. Far from it, since they carry political, cultural and, one might say, moral meanings. In a piece which appears on the HuffPost website the composer speaks eloquently about some of these meanings: “The blending of our traditional Syrian melodies and Arabic maqams with the Western orchestra, to me, is very inspiring and something I attempt to do with my compositions. This is vital because our traditions, culture and music should be documented to ensure they are not lost to the winds of time. In this way, we can re-imagine and re-interpret this traditional music for the new generation of music lovers both in the homeland and here in the United States.” As with Bartok’s use of folk materials, Jandali doesn’t see his use of them simply as an act of preservation, important as that is, but rather he clearly sees the use of “traditional Syrian melodies and Arabic maqams” as a way of giving a particular kind of vitality to his music and as a vehicle of meaning.

His violin concerto has a traditional European structure, being in three movements, marked ‘Allegro moderato’, ‘Andante’ and ‘Allegretto’. However, the music of the violin’s initial entrance is based on a Syrian source – “a samāi […] in the Zunkalah maqam […] by Aleppo musician and scholar Alī al-Darwīsh (1884-1952)” (Booklet notes by Jane Vial Jaffe). A maqam is a modal melodic structure; a samāi is an instrumental composition. Later in the movement we hear a melody played on the horn which is indebted to Syrian folk-music and which, according to Jaffe, Jandali employs as the “Women’s Theme” – the concerto being designed to honour the memory of brave Syrian women imprisoned, killed or ‘disappeared’ illegally by the Assad government. The score for this concerto makes use of an oud (the middle eastern ancestor of the lute) and its presence is particularly striking in a dialogue with the solo violin near the close of the movement, a movement full of invention and colour but also closely ‘argued’.

The ensuing Andante is melancholic, so much so that one might call it an elegy or a lament. The tone is initially set by a Syrian-influenced orchestral passage, taken up by the solo violin (in which role the contribution of Rachel Barton Pyne is movingly eloquent throughout). Four versions of different examples of traditional samā’i follow – a gently sad one played by the oboe, to which the solo violin responds, the third being played by the full orchestra, while the fourth leads into a lovely passage by the violin accompanied by the oud. After an orchestral climax, there is a heartbreakingly moving conclusion shared, again, between violin and oud. The oud is played by the Austrian-Egyptian composer and musician Bassam Halaka, who deserves a special mention.

The last movement opens, as one would expect, in more rhythmically animated fashion in a dance which is again based on a traditional samā’i,after which the oud comes under the aural spotlight once more, playing an attractive version of a piece by one of the major composers of Turkish classical music, Kemani Tatyos Efendi (1858-1913). The central section of the movement includes several passages dominated by the violin, most notably in a lively dance, which those with a knowledge of traditional Syrian music would recognise as a dance usually performed by women, and a quieter, but elegant folk tune. After a substantial climax there is pause full of tension, the silence being broken by the violin playing a slower version of the dance theme which opened the movement – an effective close to a complex and moving work which is also thoroughly accessible.

Jandali’s Clarinet Concerto is dedicated to Anthony McGill, “in memory of all victims of injustice”. Like the Violin Concerto it makes much use of musical materials from Syria. I won’t go into detail about these since the excellent booklet notes by musicologist Jane Vial Jaffe provide all the necessary information. I cannot, however, resist a mention of the second theme in the first movement (Andante Misterioso – Più Mosso) an exquisitely beautiful melody, based on a traditional Syrian samā’i.

In many sections of the concerto the clarinet part is very demanding, in technical terms, all of which the outstanding Anthony McGill surmounts without the slightest appearance of strain. One such example occurs towards the close of the third movement in an athletic cadenza in which the clarinet traverses its entire register. Jandali frequently makes perceptive use of the particular resources of the clarinet, as in his use of flutter tonguing late in the first movement.

For me the most memorable music in this concerto comes in the second movement (‘Nocturne’). Full of haunted yearning, the movement consists of six variations on a traditional Syrian muwashshah (both a poetic from and a musical genre). It is very helpful to know, courtesy of Ms. Jaffe’s notes that the title of this muwashshah is “My beloved, how did they take you from me?”. The relevance of that question to those who have been unjustly robbed of beloved individuals (or indeed homelands) by tyrannical governments is often the burden of Jandali’s music, especially in this subtle and powerful movement, which speaks of fear and loss in subtle patterns of sound and almost Bartokian ‘night music’, full of hushed and tremulous interjections, some mild dissonances and brief motifs which are soon dropped but often recur later.

The final movement (Allegro Moderato) is characterised by more forceful energies and a great variety of orchestral colours and pitches, rounded off by a spirited dance which embodies both continuing resilient defiance and the survival of hope in the midst of suffering.

I very much hope that neither my references to Jandali’s Arab sources and to the extra-musical purposes in his compositions will put off any potential listeners/purchasers. The non-Western references largely speak for themselves if you listen carefully and without prejudice – the booklet notes are, in any case, very helpful. Above all, it is important to stress that these are works of art (i.e. things that require us to be active participants, in terms both of our imagination and our reason, in determining our response to them) rather than of propaganda (i.e. things which seek to make us passive recipients, imposing on us a single meaning and doing so by trying to bypass – as it were – our analytical faculties). What must be stressed, however, is that save for a few specific works (such as ‘Watami Ana’), Jandali’s music is very much primarily ‘art’ rather than propaganda. Its political, cultural or moral significance is the product of decisions taken as an artist, not as an activist. One might draw an analogy with Picasso’s Guernica which, while it clearly carries profound moral and political ‘meaning’, is very much a work of art rather than of propaganda.

Please forgive me if I end this review on a personal but, I think, relevant note. My wife and I had a dear friend: a Syrian woman similar in age to us. We met when she and my wife were postgraduate students in the University English Department in which I was teaching. We became close friends and shared many conversations, meals, books and CDs. She was a talented artist and went on to support herself, in London, through her artwork, primarily as a painter and potter. She felt drawn back to Syria but unluckily she chose to return there only a few years before the revolution began and events soon forced her to leave her house in Damascus, along with many of her paintings. She came back to the UK, to Swansea, where we had first met and where my wife and I were still living. Though she obviously found the situation in Syria very distressing she largely remained good and stimulating company. She wrote, pseudonymously, an influential blog on affairs in Syria, but she was never physically strong and the stress and anxiety became too much for her, and she died of heart failure, almost literally in my wife’s arms. She had taught me a lot about Syrian culture and I immediately thought of her when I first heard some of Jandali’s music a year or two after her death. I very much wish that I could play this disc for her, and I know that she would have loved it. I wish, too, that I could pay a more explicit tribute to her, but even now it would probably put some of her friends and family in danger were I to name her.

Glyn Pursglove

Help us financially by purchasing from