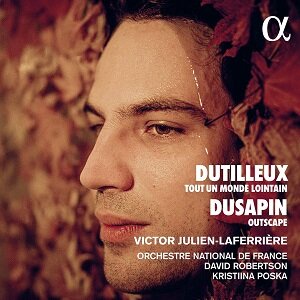

Henri Dutilleux (1916-2013)

Tout un monde lointain (Concerto for Cello and Orchestra)

Pascal Dusapin (1955-)

Outscape for Cello and Orchestra

Victor Julien-Laferrière (cello)

Orchestra National de France/David Robertson (Dutilleux), Kristina Polska (Dusapin)

rec. live, 17 February 2022, (Dutilleux); 4 February 2021 (Dusapin), l’Auditorium de Radio France (Dusapin)

Alpha Classics 886 [55]

The great Hungarian poet Janos Pilinszky once said : “I would like to write as if I had remained silent”.

I sometimes wonder if Henri Dutilleux may have felt a similar creative paradox. His oeuvre seems so slight in volume, yet so haunting and so telling in its sounds and expressions: evanescence and transparency, yet so fine-tooled and precise, then those shocking, brief, sudden outbursts! An unmistakably personal voice obsessed with the significance of every sound.

Tout un monde lointain seems borne from the silence before the first note; it concludes with an explosive outburst and an insectivorous fadeout. In the stunned silence beyond, all a listener can do is reflect upon its messages of evocation. “And that day we read no further”, as Dante remarked after the profound movement of his inner life.

This new recording conveys such veiled meanings with a paradoxical immediacy and brilliance – and couples the work with a uniquely apt cello-companion in their “undiscovered country”. Beginning with Enigme, ending in Hymne, Tout un monde rustles into existence, the music of otherness rather than a self-expression.

Can anyone “interpret” this? Or merely attempt to conjure it out of the air? The present soloist, Victor Julien-Laferrière encompasses all its effects effortlessly and imaginatively: ghostly slides in Enigma, a warm cantabile in Regard. The ONF under David Robertson responds with fierce surges, summoning sonorous mysteries around the lone voice. What a sweet, clear upper range this soloist produces! (a Montagnana cello, the bow by Peccatte). Through Houles and Miroirs, one hears and feels how closely the accompaniment follows and feels the cello; both prompt a dialogue, a Boulezian double shadowing with wonderful orchestral control. Robertson ignites an instrumental detonation and shatters the mirrors. So we pitch into the restless, fiery, final-but-not-so-final hymn; after shockwaves of orchestral colour at once exultant and angry, the cello’s last gesture like a buzzing firefly, fading away into darkness…(the sound will continue, out of earshot, somewhere else, in a parallel sonic universe….).

The busiest movements of the piece, Houles and Hymne, prompt the thought of an urgent need to say as much as possible, as fast as possible, with as few gestures as possible; sound poetic principles: Dichten = Condensare.

Tout un monde is a lucky work on record; among the best I’ve personally favoured are Mose/Søndergärd (Pentatone), Philips/Morlot (Seattle SM) and among the less noticed, the mesmeric articulations of Queyras/Hans Graf with the ONB of Aquitaine, in the composer’s presence, on Arte Nova. (Do check out this last and mostly overlooked issue, indeed the 3-disc series devoted to Dutilleux by the same orchestral partnership; despite some lack of acoustical space and air, it is one the finest Dutilleux capsule-collections you’ll find. The overseeing ear of the creator spiritus has nurtured a marvellous, or marvelling, idiomatic warmth).

Suffice it to say that this latest recording, with spacious, vivid and dynamic recorded sound, is a match for any precedent – but this is a work which seems always to float and fly clear of most interpretive differences; one finds comparison and contrast in tonal character, soundstaging, time passed/elapsed, orchestral sonorities and the conductor’s balancing of evocation and definition. That said, the sheer beauty of Julien-Laferrière’s cello-voice, and the range and brilliance of Robertson’s ONF, make this one special.

Concertante sounds, thoughts and forms, endlessly renewed, have often vitalised the music of Pascal Dusapin; perhaps more in a Baroque mode, with continuous interplay and evolution rather than any Romantic oppositions and reconciliations of band versus solo. The title of his greatest and most epic orchestral statement is, of course, Seven Solos for Orchestra, through whose often furious, massive intensities solos and concertante-style groups glitter like minerals in the strata of a rockface. He even speaks of “that large solo instrument constituted by the orchestra” which may “sing in unison” as it does at the very start of Go, the Solo No.1. Why are they called “Solos”? Because they are not “Concertos”. Yet they can sometimes sound like “Concertos for Orchestra”, not too far from Petrassi in this respect. Terminology and titling is provocative in Dusapin: what are you listening to? What are you doing when you listen?

The questions continue: the 6th Quartet “Hinterland” is for…String Quartet and Orchestra. The Orchestral work “Morning in Long Island” is subtitled “Concert for Orchestra”. Writing as if you had remained silent? The Orchestra as a solo instrument? Welcome to the modern world. Two other modern orchestral epics composed across several years, Cerha’s Spiegel and Grisey’s Les Espaces Acoustiques, are irresistibly drawn to mind; both 90 minutes or more, in six or seven sections. I wonder if Dusapin was consciously facing such a challenge – a traditional succession.

In some Dusapin works, the musical texture and direction shift restlessly, but calmer, contemplative flowing sounds are usually offered to the listener at some point of reflection, and in the case of this 2017 work for Cello and Orchestra, Outscape, are its most essential characteristic. “Outscape”…. what does the word bring to mind? To me, the inner world projected; perhaps a point at which the mind-world meets the land-world, the landscape feeds back into the mind, as a spiritus loci? Why did it seem so familiar? Because of its opposite, “Inscape”, a term of poetics probably originated by Gerard Manley Hopkins, to evoke the uniqueness of individual inner lives and the uniqueness of phenomena in the natural world, in a religious or metaphysical sense.

As Dusapin makes clear in his YouTube talk about the work, he knew of this very word, and was led to the term “Outscape” because of it. He comments further in the notes: “Outscape is the pathway, or the opportunity of escaping, of inventing one’s own path. I really like this word, because basically it sums up the story of my work, the idea of fleeing to a different place, in order to understand, to discern, to try to see and hear what is further away. That is how this concerto invented itself, in constant comings and goings between the cello “becoming” an orchestra and an orchestra “becoming” a cello”.

Let us see, or hear, how this works out in the act of listening. I often like to transcribe my thoughts on a first musical encounter, almost an automatic-writing-response to the sounds which bear in upon me; this, with minor corrections for typo and syntax, is how it went…..

…the cello sings a sombre song, bass clarinet follows and echoes….a muffled drum strikes distant single notes, like a bittern in a reedbed…piccolo has an otherworldly birdcall…Gradually life spreads though the orchestra….bleak taps on woodblocks, spiky trumpets, floating, spectral strings…. the cello agitates, the muffled drum rolls, the flute comments from within its own natural world…Dense textures, brasses hint at a threat…the cello tries to rise, to sing higher….the violins follow, the atmosphere is eery, ethereal…a clarinet’s static song, trumpets birdcall, the textures settle into a sonic snowdrift…Towards midpoint, the cello differentiates against the floating strings in troubled solo lines, percussion twinkle, brasses snarl; stasis in gongs and drums….a long pause. Cadenza-like cello, cantabile, the bleak taps, strings dimly floating…the cello seeks escape! But falls back…. A sudden eruption in the orchestra, the cello disappears, bass clarinet into the foreground, disruption in drums and trumpets, cello returns in chatter and gabble, trumpets follow high-speed, a great instrumental violence! Cello sings sorrowful, then agitated, pitched percussion imitate, winds follow…. All is drawn into a whirling wild finale, until the orchestra stamps upon the cello’s writhings – enough! Violins float…calm, motionless, the flute-bird calls in the night….the before and the after, in my end is my beginning….the cello’s final fade….beyond silence….

Repeated listening drew the eagle’s eye across the landscape, revealing a continuous, essentially melodic metamorphosis of the key elements: the solo itself (with clarinet often in close attendance), smaller groups (often of winds in timbral support of the cello), and larger sections of strings and brasses, the latter breaking into and across the evolutionary flow. I could hear more clearly the cello, orchestra and instrumental groups “becoming” each other: imitating and echoing each other in their lines and sonorities, simultaneously and continuously, not in any linear transformative way. The piece can sound like a long, eventful, interrupted crescendo, peaking in excitement around 15’; then a pause to reflect and recapitulate; then a finale-crisis through wavelike climaxes and a coda where darkness descends around the cello’s stoical voice.

This is an outstanding album in fine recorded sound: the densely layered timbres are both transparent and natural; the dynamic energy immediate in its communication of two vividly contrasted works, the short, shapeshifting facets of the Dutilleux and the sustained singing intensities of Dusapin’s land of the mind (or just call it as an Adagio for Cello and Orchestra). I’ve come to love them both very much.

If you wish to explore the Dusapin Concerto oeuvre further, I would recommend the Concertos on Naive MO782153: Watt, Galim, Celo – a pithy, dark yet playful one for trombone, an intense lament for cello, separated by a hovering, floating meditation for flute and strings. The Trombone Concerto, Watt, features a passage where the soloist sings into the instrument whilst playing a pedal B-flat, doubling piccolo at the lower octave, producing a haunting, tragi-comical lyricism, so apt to its Beckettian inspiration; I’ve heard nothing else quite like it. The more extended creations of the Violin and Piano Concertos on BIS-2262, Aufgang and à quia, are also among this extraordinary composer’s most extraordinary utterances.

Time spent in the parallel musical universe(s) of Pascal Dusapin can be transformative. The self that returns to the material world may not be the one that left it….

Jayne Lee Wilson

Help us financially by purchasing from