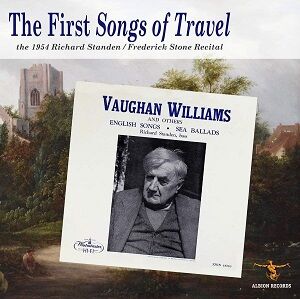

The First Songs of Travel

Richard Standen (bass-baritone)

Frederick Stone (piano)

rec. Autumn 1954, Westminster’s London Studios for Westminster LP

Texts included

Albion ALBCD055 [57]

My previous encounters with bass-baritone Richard Standen have been in Bach but Albion’s reissue of his 1954 Westminster LP devoted to British song is wholly new to me. It was a remarkably long LP for the time, lasting 57 minutes, and it’s here heard in full. Standen (1912-1987) worked on disc with Scherchen, most notably in the St Matthew Passion, Messiah, Beethoven’s Ninth and Mozart’s Requiem, but he also sang in the premiere recording of Tippett’s A Child of Our Time in John Pritchard’s recording.

Here he sings the first Songs of Travel on disc – the then eight songs, not the set of nine as the ninth, I Have Trod the Upward and the Downward Slope was only discovered after the composer’s death. Standen took the idiosyncratic decision – or Westminster did – to sing them in an ordering of (presumably) his own devising, which is to say 1, 8, 3, 2, 4, 5, 6, 7 whilst retaining the original publisher’s two parts: first part, three songs, second part four songs, and Whither Must I Wander standing separate, if it reflects the LP track listing accurately, which I assume it does. Five of the songs in the set were heard here in first performances on disc.

Standen also sang under VW in the Bach Passions and it appears VW admired this recording of the songs. That would be wholly understandable given that Standen was making them available as a set for the first time and giving premiere recordings as well. Standen has a dignified oratorio singer’s approach, and almost wholly a townsman’s conception of the set. He’s also inclined on occasion to hector and become stentorian. Of light and shade, whether because of the microphone set-up or Standen’s practical, stand-and-deliver approach, there’s not that much to be heard. He does vary things in Bright is the Ring of Words but he tends to be quite military with the texts. Frederick Stone was a long-time BBC accompanist, best remembered on disc for accompanying Ferrier, but he tends to plod in The Vagabond. Of sensuality and voice floating there’s nothing to be heard in Let Beauty Awake, one of VW’s most beautiful songs.

Standen’s Songs of Travel was fairly soon to be relegated when John Shirley Quirk’s version with Viola Tunnard appeared. Rather naughtily, Saga chose to reproduce not only Westminster’s two-part LP approach – with the cycle on one side and miscellaneous songs on the other – but they also took seven of the same (well-known) songs Standen sang. This was tough on Westminster and on Standen but it can’t be denied that in almost every song Shirley-Quirk’s intimacy, attention to detail and to vocal meaning is immeasurably superior to Standen’s and that Tunnard is a more thoughtful accompanist than Stone.

Nevertheless, it’s stylistically interesting to hear the miscellaneous songs. Standen wanders through Silent Noon like a man in a Garden Centre appraising the hanging baskets. Neither rapture nor sensuality interrupt his hands-behind-the-back saunter. Shirley-Quirk shows how it should be done and before him, Heddle Nash, though past his best, does so even more in his 1952 version for HMV. There’s little inflexion or nuance in Linden Lea – here Standen uses the microphone as if addressing an audience at the Crystal Place in 1898 – and not every singer in the country sang it ‘Lin-den’ in 1954. Nash, in the studio or live, is the great example. The Water Mill is novel and interesting VW repertory, certainly for the time – even today – but it needs far more variety of tone, expressive breadth and light and shade; though he did study it with VW himself, apparently.

No, these confided intimacies are not Standen’s thing and I think he was fundamentally miscast. Where he is better is in Warlock and Stanford, where one senses his forthright, bluffer self can make better headway; here, Shirley-Quirk doesn’t quite measure up to Standen’s swagger. One doesn’t believe for a second that Standen was a seafarer, but his Ireland Sea Fever is creditable. This was also the disc premiere of all of Frederick Keel’s Three Salt-Water Ballads and they make a good impression, Port of Many Ships especially. For my tastes Trade Winds is altogether too lugubrious, and Shirley-Quirk, who sang just this song from the three on his disc, is a nimbler, more urgent interpreter. A couple of songs by Michael Head and single ones by Malcolm Davidson and Albert Mallinson show the variety to be encountered in Standen’s disc and whilst I find many things stylistically limited about his singing, one shouldn’t overlook the breadth of the English repertoire he promoted. In these less well-known songs one can feel glimmers of the conversational.

There’s no doubting the fine restorations or the admirable booklet, which prints full texts and has intelligent things to say about the songs and artists. This is nevertheless a curio, a recital of ‘Vaughan Williams, English Songs and Sea Ballads’, as Westminster’s LPs had it – it was released on XWN 18710 and WLE 103 – which was sunk for many decades, until now.

Jonathan Woolf

Help us financially by purchasing from

Previous review: Nick Barnard (June 2023)

Contents

Ralph Vaughan Williams (1872-1958)

Songs of Travel (1901-04)

The House of Life: Silent Noon (1903)

Four Poems by Fredegond Shove: The Water Mill (c.1922)

Linden Lea (1902)

J Frederick Keel (1871-1954)

Three Salt-Water Ballads (pub 1919)

Michael Head (1900-1976)

Six Sea Songs: Limehouse Reach; Sweethearts and Wives (1949)

Charles Villiers Stanford (1852-1924)

Songs of the Sea, Op.91: Drake’s Drum; The ‘Old Superb’ (1904)

John Ireland (1879-1962)

Sea Fever (1913)

Albert Mallinson (1870-1946)

Four by the Clock (pub 1901)

Malcolm Davidson (1891-1949)

A Christmas Carol (1920)

Peter Warlock (1894-1930)

Captain Stratton’s Fancy (pub 1922)