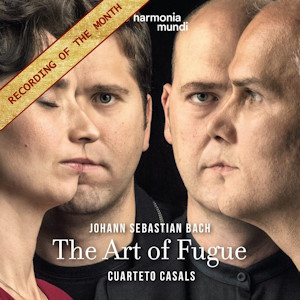

Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750)

The Art of Fugue BWV1080

Chorale ‘Vor deinen Thron tret’ich’ BWV668 (from 18 Chorale Preludes BWV651-668)

Cuarteto Casals

rec. 2022, Castell de Cardona, Spain

Reviewed as a digital download from a press preview

Harmonia Mundi HMM902717 [68]

Amongst the many challenges presented by performing The Art of Fugue, setting aside the question of whether it was ever intended for performance in the first place, is how to avoid monotony from a series of contrapuntal works all in the same key and based on the same tune. One very cogent argument goes that such is Bach’s genius at exploring virtually every conceivable way of writing contrapuntally that there is no risk of boredom if the listener is sufficiently attentive. Whilst this is unarguable, less attentive listeners may require a little sweetening of the pill.

One of the great strengths of this new recording by the Spanish Cuarteto Casals is its pacing. Bach took great care to ensure not only that each fugue, or Contrapunctus or Canon to use the terminology he deploys in this score, demonstrates a particular technique but that each has its own distinct musical character. Drawing out those characters can be sufficient to vary the various movements. As well as giving each section its own special personality, the Casals traces an almost symphonic trajectory across the work.

As movement succeeds movement the effect is very similar to the cumulative impact of an apparently more unified but, it turns out, not all that different work like the Goldberg Variations. The Casals judiciously vary the tempi, so we get fast and slow sections, as well as the mood to give us reflective or extrovert movements in addition to the increasing complexity in terms of counterpoint. Whilst they may occasionally allow the mood to relax a little, there is a rising sense of excitement and pressing on as the work proceeds.

The opening Contrapunctus, for example, might seem a little lacking in impetus taken individually but seen against the rest of the work as a whole it feels more like a gentle, careful laying out of the main theme and, if such an idea can ever can apply to Bach, a straightforward fugal treatment. Barely discernible at first in this opening fugue, there is a kind of heartbeat that pulses inexorably through everything that follows. I say heartbeat because there is nothing metronomic or mechanical about the playing of this quartet. The superb, compendious booklet that accompanies this release takes the form of an interview with the musicians. In addition to the peerless advice to any listener new to The Art of Fugue to simply ‘be present’, they state that they decided to present the work ‘in the most human way possible’ with ‘each voice part… an embodiment of the deeply fallible people we are.’ It is out of this combination of four fallible people that ‘the divine can be glimpsed.’

That marriage of the human and the divine is the glory of this set. I have always found it hard to believe that there are those who think that this work is an emotionless if dazzling technical piece. Of course it is a dazzling technical feat but listen to the heart and soul the Cuarteto Casals find in it! To start at the end, have a listen to quiet, awestruck humility and gratitude that the concluding Chorale exudes. I don’t want to get into any kind of debate about the fact or more likely fiction of whether this Chorale setting, here arranged for string quartet, was Bach’s last work, dictated on his deathbed. I will content myself with the observation that in this context, coming after a completed version of the final fugue left incomplete by Bach, it works. It is like a musical equivalent of Bach’s usual sign-off at the bottom of his scores, SDG, solo Deo gloria – to God alone be the glory.

There is a refreshing lack of stultifying reverence that mars too many accounts of The Art of Fugue. The new version of it by the Richter Ensemble accompanied by some first-rate Webern is a case in point. The Casals are not afraid to dance a jig or even crack a joke when needed. One minute they seem gathered at the foot of the cross, the next accompanying Christ on his harrowing of hell. They can be so delicate that they virtually seem to be breathing on the strings and then immediately they are full of vibrant, robust life. Throughout it all, they are engrossed in deep conversation with one another.

Playing this music with a string quartet, with some adjustments where Bach’s voices go beyond the range of the instruments, makes good sense, giving something of the sound of a viol consort to the performance whilst retaining the greater agility that violins, a viola and a cello bring. One of the unexpected pleasures is a distinct flavour of the late Beethoven quartets. The anonymous interviewer behind the liner notes asks the quartet if they imagined how Bach would have written for string quartet if he had lived long enough to see it. The answer given by the recording is, triumphantly, exactly like this.

The quartet credit the acoustic of the Castell de Cardona as the fifth member of their ensemble and with good cause. The Harmonia Mundi do that magnificent space proud in sound that is as good as the music and the performance of it. This now stands at the top of my list of recordings of The Art of Fugue and is one of highlights of this year’s new releases.

David McDade

Help us financially by purchasing from