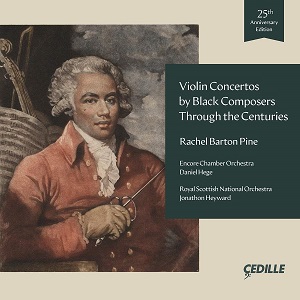

Violin Concertos by Black Composers Through the Centuries

Joseph Bologne, Chevalier de Saint-Georges (1745-1799)

Violin Concerto in A major, Op 5 No 2 (1775)

José White Lafitte (1836-1918)

Violin Concerto in G-sharp minor (1864)

Samuel Coleridge-Taylor (1875-1912)

Romance in G major for violin and orchestra, Op 39 (1899)

Florence Price (1887-1953)

Violin Concerto No 2 (1952)

Rachel Barton Pine (violin)

The Encore Chamber Orchestra of the CYSO/Daniel Hege

Royal Scottish National Orchestra/Jonathon Heyward (Price)

rec. 1997, Chapel of St. John the Beloved, Arlington Heights, USA; 2022, Scotland’s Studio, Glasgow, UK (Price)

Cedille CDR 90000 214 [73]

It was a breath of fresh air when, a quarter-century ago, in 2001, violinist Rachel Barton Pine founded the Rachel Barton Pine Foundation, starting the initiative named Music by Black Composers and recorded three concertos for Cedille by Black composers. This anniversary reissue adds a concerto by Florence Price.

Joseph Bologne is often decribed as ‘The Black Mozart’. But he was born eleven years before Mozart and outlived him by eight years, so, as Rachel Barton Pine says, ‘it should really be the other way around, with Mozart as “The White Bologne”’. It would be easy to dispute that, but the concerto on this programme stands up to the closest scrutiny as brilliant, charming and very well written. It employs many of the elements that mark out Mozart as an outstanding composer. I expect that in a ‘blind’ audition many listeners would indeed say that it was Mozart’s. There are techniques here, including music that requires playing right up to the end of the fingerboard, which Mozart apparently applied only after hearing this piece.

Notable composer and violinist Antonio Lolli wrote two concertos for the nineteen-year-old Bologne. He was an accomplished violinist by then, eleven years after his plantation-owning father had brought him to France for his education. It may be a surprise that his 236 compositions include fourteen violin concertos and eight operas, plus 115 songs and it will surely be a further surprise that it was his commission we have to thank for Haydn’s six Paris Symphonies. He was among the first French composers to write string quartets and symphonies. In short, Mozart was as much influenced by Bologne as Bologne was by Mozart.

The opening of this concerto, immediately appealing, launches into a catchy, delightfully simple and earwormingly seductive tune. It is reworked and improvised upon throughout the first movement; I could not tire of hearing it. The Largo second movement is sober by comparison, but still gives us eight minutes of beautiful melodies. The Rondeau finale is a spirited affair, with more attractive tunes running through its four-and-a-half-minute span. I believe many a violinist would be eager to include it in their repertoire; it really is that satisfying to hear.

Musicologist Mark Clague’s booklet notes point out that the concerto could also be described as a duo concertante for soloist and orchestra. Bologne introduces numerous melodies, some regrettably left undeveloped. As many are given to the orchestra alone as to the soloist. He shows a remarkable facility with supremely listenable music, and is never lost for ideas. (One might imagine that Salieri could have been equally jealous of this virtuoso.) It turns out that he was also skilled at fencing. Rachel Barton Pine is quite convinced that the considerable demands he places on the bow arm can be attributed to those abilities.

From almost a century later, we have a violin concerto by Cuban-born José Silvestre de los Dolores White Lafitte. His father was a white French businessman, and his mother was Afro-Cuban. The indefatigable touring virtuoso pianist Louis Moreau Gottschalk accompanied White in his debut at 18, when he played a fantasy on themes from Rossini’s William Tell plus a couple of his own compositions. Gottschalk encouraged the young man to study further in Paris, and raised the money to send him there. As if that was not remarkable enough, White bested sixty rival applicants to the Paris Conservatoire to study with the leading violinist of the day, Jean-Delphin Alard. At twenty, he won the Prix de Rome in violin. His tours in Europe, the Caribbean, South America and Mexico made him famous. Rossini himself wrote him a letter of praise: the French violin school should be proud of his ‘elegance, (the) brilliance […] (and) qualities’.

These qualities are obvious in the violin concerto, which begins with a haunting theme. What a critic wrote of the première given by White himself is no surprise: ‘there was not a single superfluous note in the entire concerto nor any that were included merely to show off’. The second theme, equally satisfying, flows melodiously towards the movement’s close. The second slow movement has animated sections which further show that the concerto makes serious demands on the soloist’s abilities. The finale is in the popular Gypsy-like mode, with the kind of flamboyant violin pyrotechnics late 19th-century audiences loved. I bet it went down a storm, so why was it only in 1975 that it received its first recording? That seems to be the only one before the present version; try as I might, I could not find others. I hope that other violinists take it up. It is a more-than-deserving inclusion in any violinist’s repertoire.

Samuel Coleridge-Taylor’s fairly well known Romance is yet another persuasive example of Black composers’ ability to write fine music. There have been recordings better than this one – the orchestral accompaniment lacks the heft that others have achieved – but that is not a reason to pass up this important disc. Full of luscious harmonies, the Romance never outstays its welcome. It reminds us that we should seek out more of this outstanding composer’s works to play and enjoy.

A work which might have completed the disc was the Concerto No 4 by Le Chevalier de Meude-Monpas, which Rachel Barton-Pine has also recorded. It has turned out, however, that he was not Black. Instead, the programme includes Rachel Barton Pine’s recent recording of US composer Florence Price’s concerto. Price’s black, white and Native American heritage makes her a true personification of her country’s diversity, and her music is now enjoying a renaissance. The short concerto – recorded a few times recently – could also easily be considered a romance or rhapsody. It is full of sumptuous melodies, and never fails to please. It is uncomplicated and straightforward, and very easy on the ear.

The pioneering work of people like Rachel Barton Pine allows the music by Black composers to be heard more and more often. She is a deeply committed and highly talented artist. Her infectious delight in bringing these works to the notice of the listening public is obvious. In respect of the first two works, the disc has lost none of its ground-breaking importance – and there are enough works by Black composers to keep her and like-minded people busy. Bring them on!

Steve Arloff