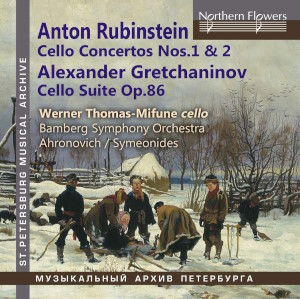

Anton Rubinstein (1829–1894)

Cello Concerto No. 1 in A minor, Op.65 (1864)

Cello Concerto No. 2 in D minor, Op.96 (1874)

Alexander Gretchaninov (1864-1955)

Suite for cello and orchestra, Op.86 (1925?)

Werner Thomas-Mifune (cello)

Bamberg Symphony Orchestra/Yuri Ahronovich (Rubinstein), Alexander Symeonides

rec. 1986-89, Munich

Northern Flowers NFPMA99150 [79]

This densely packed CD lends new life and vigour to the contents of two CDs from the first decade of the 21st century. What they have in common is the admirable but little spoken-of cellist, Werner Thomas-Mifune (1941-2016). The earlier discs in question are VMS Musical Treasures 601 (from 2008) for the Rubinstein, and Koch Schwann Musica Mundi CD 311 008 (1986) for the Gretchaninov. This disc also packs a punch away from the familiar and does so with some real conviction in the hands of the soloist and his conductors.

Rubinstein’s two cello concertos are statements of length and substance; qualities not always going hand in hand. The writing is rounded and moderately Tchaikovskian. Often, they are not especially Russian in flavour – less (in fact hardly any) of the Kuchka and more of the cosmopolitan material and finish for which this prolific composer was renowned. It took me back to the same composer’s Ocean Symphony which years ago I quite unreasonably had hoped would have delivered more of the high seas, storms and spume and glistening dawns at sea.

The 35-minute First Concerto, in three movements, ploughs a singing furrow with chances to shine through burnished poetry and virtuosic display. It reminded me at times of Tchaikovsky’s Rococo Variations. The middle movement sings thoughtfully and most satisfyingly. The finale, in its preliminaries, storms along in bel canto manner, but all bows down to the expression of the lyric impulse when the cello enters. The work ends with a majestic statement and a tempest of virtuoso flamboyance. The shorter Second Concerto has, according to Gavin Dixon’s exemplary and readable notes, a more ‘Russian’ flavour, which I take to mean nationalist. In that sense I would agree. There are, for example, several folk-dance moments, as at 2: 22 in the first movement. A songful soul is revealed in the middle movement and Thomas-Mifune happily colludes in the expression of this mood. In the distinctive finale, which at first crashes about melodramatically, the composer soon finds its centre of emotional gravity, light on its feet and toe-tapping. The Second Concerto is likely to win converts more ably than the First.

Gretchaninov is of a later generation, with his maturity coming after Rubinstein’s death. A Muscovite, he studied with Arensky and Taneyev. Ultimately unhappy with this, he packed his bags and decamped to St. Petersburg where Rimsky-Korsakov taught him. The shocking upheaval of the Revolution left him with little choice other than to move to Paris in 1925 and then to the USA in 1939. If you want to delve more thoroughly into Gretchaninov’s music then try the cluster of this composer’s discs on Chandos.

The quarter-hour four-movement Cello Suite has a sparkily explosive Ballade. I would have expected more poetry from the composer but he seems to have held that in reserve for the moonlit Nocturne and the profane seductions of the Prière pave the way for the short, sharp farewell that comes in the form of the little Arabesque. The writing has about it more of early Stravinsky, Balakirev and especially Rimsky. I wondered if the composer had designs on Diaghilev adopting this music for the Ballets Russes series. The Suite fits the ‘specification’ both in duration and character. Such multifarious variety made me think of other suites (not quite concertos) for solo instrument and orchestra including those by Taneyev and Bridge.

As a Northern Flowers CD, this departs from that label’s usual byword. The music is Russian, of course, but St Petersburg/Leningrad links are not to the fore, although Rubinstein did found the St Petersburg Conservatory. It hardly matters, as the music and the music-making is pleasing, well despatched and well recorded. The St Petersburg/Leningrad factor is, after all, a trivial issue; almost as negligible in sheer musical terms as the ‘departure’ represented by Lyrita’s set of concert radio broadcasts by Nikolai Malko.

A disc that has the cello as a key to the Russian cosmopolitan and nationalistic worlds, all well focused by artistry, technicalities and annotation.

Rob Barnett

Help us financially by purchasing from