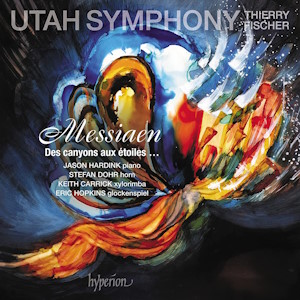

Olivier Messiaen (1908-1992)

Des canyons aux étoiles (1974)

Jason Hardink (piano); Stefan Dohr (horn); Keith Carrick (xylorimba); Eric Hopkins (glockenspiel)

Utah Symphony/Thierry Fischer

rec. 2022, Abravanel Hall, Salt Lake City, USA

Hyperion CDA68316 [2 CDs: 92]

Throughout his compositional career Olivier Messiaen wove deep into his music both his Catholic faith and his passion for birdsong. Arguably, Des canyons aux étoiles represents the apogee of his depiction of what he would have termed the wonders of God’s Creation.

This remarkable score was commissioned from him by Alice Tully in 1971; the intention was to celebrate the bicentennial of the USA in 1976, though in fact the premiere took place in New York in 1974. Paul Griffiths says in his valuable booklet note that the work was completed that year. Oddly, though, in the booklet of Warner’s Messiaen Edition set, issued in 2000, the date of what I believe was the work’s first recording, made by Erato, is given as 1973. That Erato recording was conducted by Marius Constant and the hugely demanding piano part was played by the person for whom it was conceived: Yvonne Loriod.

The scoring of Des canyons aux étoiles is quite unusual. Messiaen uses very large forces comprising 14 woodwinds, 10 brass (including the solo horn), no less than seven percussionists (including the two soloists), and piano. However, the string choir is not in proportion. There are just 13 individual string parts (though 14 players are listed in Hyperion’s booklet).

How appropriate that this recording should have been made by the Utah Symphony since Messiaen was inspired by the remarkable geographic formations of the state, which he visited in 1973. The booklet includes 2 photos of him in one of the Utah canyons, transcribing birdsong I strongly suspect. There’s also a picture of a plaque put in place in Cedar Breaks National Monument, denoting ‘Mount Messiaen’ and specifically celebrating the composition of Des canyons aux étoiles. Paul Griffiths’ note contains a fascinating reference to what appears to have been an open-air performance of Messiaen’s score prior to this recording. Intrigued, I looked on the Utah Symphony’s website and there discovered an old press release from which I learned that on 2 June 2022, in the midst of the recording sessions, Fischer and the orchestra performed the work at the O C Tanner Amphitheater adjacent to Zion National Park: what an extraordinary experience that must have been for musicians and audience alike. The photograph on the website shows the amphitheatre with its amazing natural backdrop. This recording seems to have been something of a project because I learned also that Fischer has programmed individual movements from Des canyons aux étoiles in various concerts since 2019; that’s an excellent idea, since it must have helped give the Utah audiences a degree of familiarity, which is much better than simply confronting them with this vast ninety-minute work all in one go.

I’ve never had the opportunity to hear the work live but fortunately there have been several excellent recordings of it. I first became acquainted with it through the recording that Esa-Pekka Salonen made for what was then CBS Masterworks in the 1980s (review). Subsequently, I acquired the aforementioned Constant recording and in 2015 I reviewed a fine live account conducted by Christoph Eschenbach. I can honestly say that this new Thierry Fischer version is as fine as any I’ve heard.

Des canyons aux étoiles consists of twelve movements and is divided into three parts. I think I can best illustrate the thinking behind Messiaen’s composition by repeating some of the composer’s comments about the score which were included in the booklet for the aforementioned Eschenbach recording. Messiaen said that the work depicts “…ascending from the canyons to the stars – and higher, to the resurrected in Paradise – in order to glorify God in all his creation… Consequently, it is first of all a religious work, a work of praise and contemplation. It is also a geological and astronomical work; a work of sound colours, where all the colours of the rainbow revolve around the blue of the steller’s jay and the red of Bryce Canyon.”. The composer mentions one bird in that comment but, in truth, the score might be described as a musical aviary, so rich is it in birdsong. For the last few years my daughter, an avid birdwatcher, has been living and working in the USA. She’s mainly been based on the eastern seaboard but even so the photos that she’s posted on line – and there have been a lot! – have given me an appreciation, which I previously lacked, of how varied and often exotic is the bird population of the USA. Messiaen’s use of birdsong in this particular work is stunning in its variety and colour.

Four soloists are credited in Des canyons aux étoiles but, in truth, every musician involved has a virtuoso part to play and there’s no hiding place. I think the members of the Utah Symphony do a stellar job. The two most prominent solo parts are for the horn and the piano. The horn player contributes within his section – Messiaen specifies four horns – but there are also many significant solo passages, including one entire movement, ‘Appel interstellaire’ in which the horn plays alone. Throughout the five-minute duration of that movement. Messiaen requires the horn player to use a daunting array of unusual techniques. Stefan Dohr, the principal horn of the Berlin Philharmonic, plays with staggering virtuosity – as he does elsewhere – and makes this movement a standout moment in the performance.

As I mentioned, the piano part was conceived for Yvonne Loriod and usually one finds a ‘big name’ pianist involved – for example, Paul Crossley plays for Salonen and Tzimon Barto for Eschenbach. I’d not encountered Jason Hardink before. He’s the Principal Keyboard player with the Utah Symphony but its clear from his biography that he’s a significant soloist in his own right with a leaning towards contemporary music. He has Vingt Regards sur l’Enfant Jésus in his repertoire and it’s obvious from his performance here that he’s fully in tune with the Messiaen idiom. He plays the immense solo part with great virtuosity and panache. I was seriously impressed by his performance, not least in the two fiendishly demanding movements for solo piano.

Hardink is to the fore in the second movement, ‘Les orioles’ in which Messiaen depicts no less than six different varieties of this bird. The piano and xylorimba take the lead in recreating for us the songs of these birds. The vast battery of percussion includes an instrument of Messiaen’s own devising: a geophone or sand machine. Paul Griffiths explains that this is a large flat drum, filled with lead beads which is rotated in order to produce a sound akin to that of shifting sand. The geophone is joined in the percussion battery by an éoliphone (wind machine). The geophone makes its first appearance in the third movement ‘Ce qui est écrit sur les étoiles’. It’s a most unusual sound and illustrates how keen was Messiaen’s ear for the sonorities he wished to create. Elsewhere, he achieves his aims through the use of conventional instruments but he uses them in an audacious and highly imaginative way: the score positively teems with inventive orchestration.

The fifth movement, ‘Cedar Breaks et le don de crainte’ (Cedar Breaks and the gift of awe) is a choice example of Messiaen’s inspired scoring as he depicts the landscape and some of the avian life to be found within it. The movement includes some truly awesome chorale-like writing for the brass but there are countless subtle touches too. Furthermore, the entire movement is full of arresting colours and rhythmic patterns. The seventh movement, ‘Bryce Canyon et les rochers rouge-orange’ is, in this performance, the longest movement; it’s also arguably, the most complex. Birds are much in evidence, of course, but it seems that Messiaen’s prime concern is to celebrate ‘les rochers rouge-orange’ (the red-orange rocks). The music is stunningly vivid. This amazing section of the work is superbly played.

Part III of Des canyons aux étoiles opens with a movement entitled ‘Les ressuscités et le chant de l’étoile Aldébaran’ (The resurrected and the song of the star Aldebaran). In his own commentary on the work, the composer explains that Aldebaran is the brightest star in the Taurus constellation. It’s a lush movement, comparable in some ways to the ‘Jardin du sommeil d’amour’ movement from Turangalîla-symphonie, though not as overtly sensual. We hear slow, long-breathed string phrases around which the woodwind and percussion (representing the resurrected) dance. In one of the countless subtle touches that permeate this score, Messiaen adds an intriguing sheen to the string line by having the first violin (in harmonics) and the crotales double the melody. This mystic movement is gorgeously performed by Fischer and his orchestra. Given that this is a score inspired by Utah I don’t quite know why the penultimate movement, ‘Omao, leiothrix, elepaio, shama’ is constructed round the songs of the four birds of the title, all of which are native to Hawaii. It matters not; their songs are translated into exultant, vibrant music which here receives a performance that is energetic and exciting.

Messiaen’s great hymn to the topography and avian population of Utah concludes with ‘Zion Park et la cité céleste’. The movement is anchored by a slow, majestic brass chorale. Around this a multitude of birds swoop and carol. The music is ecstatic and culminates in a wonderful, extended chord, exultantly decorated by various instrumental flourishes. The chord is a true moment of arrival and completion.

Des canyons aux étoiles contains fabulously imagined, visionary music. It doesn’t perhaps have the immediate sensory appeal of Turangalîla-symphonie and, of course, between the late 1940s when he wrote the symphony and the early 1970s when Des canyons came into being, Messiaen’s musical language had evolved and developed; in so doing, it had become rather more challenging. That said, Des canyons is a hugely rewarding score and one that appeals to the senses. It’s a formidable achievement; another of the composer’s great hymns to Creation and his Creator – though you certainly don’t need to subscribe to Messiaen’s religious ethos to appreciate this score.

The present performance is superb in every respect and the musicians’ skills are complemented by an excellent recording which enables all the myriad details of Messiaen’s scoring to shine though. Paul Griffiths’ notes guide the listener through the key points of the work.

Thierry Fischer is leaving his post with the Utah Symphony at the end of the 2022/23 season – I see that his penultimate programme with the orchestra will be Turangalîla-symphonie (with Jason Hardink as pianist). During his time with the orchestra, they have enjoyed a fruitful partnership with Hyperion. Presumably this will be the last recording they’ll make together. If so, the partnership has ended on a high note.

Help us financially by purchasing from