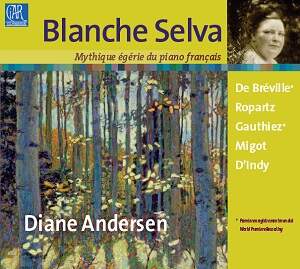

Hommage à Blanche Selva

Mythique égérie du piano français

Pierre de Bréville (1861-1949)

Stamboul, rythmes et chansons d’Orient (1895)

Guy Ropartz (1864-1955)

Nocturne No. 2 (1916)

Cécile Gauthiez (1873-1944)

Fête béarnaise (1921)

Georges Migot (1891-1976)

Le Tombeau de Dufault, jouer de luth (1923)

Vincent d’Indy (1851-1931)

Thème Varié, Fugue et Chanson, Op.85 (1925)

Diane Andersen (piano)

rec. 2020/21, Studio Recital B, Tihange, Belgium

Ciar Classics CC012 [67]

Blanche Selva (1884-1942) was a distinguished proponent of French pianism in the first half of the 20th century. Early on she began piano lessons with Sophie Chéné, eventually entering the Paris Conservatoire. She was quickly spotted by Vincent d’Indy, who later appointed her professor of piano at the city’s Schola Cantorum when she was just eighteen. She fulfilled a dual role throughout her life as a teacher and successful concert pianist. In the latter capacity she championed such composers as Albéniz, Roussel, de Séverac, Dukas, Roparz and Magnard. This latest release from Ciar Classics features some of the works dedicated to her, and which she premiered.

Pierre de Bréville’s Stamboul (Istambul) is an exotic study painting in the Saint-Saëns mold. He’d visited Constantinople in the early 1890s, and from thereon an “Orientalist” strain crept into his music. Stamboul, in the form we hear it here, had a lengthy gestation. It began life as a three movement piano suite, penned in 1894-95. This was later orchestrated and premiered in April 1900. In 1913, the composer added another movement (Le Phanar), and this four movement orchestral suite had a premiere that same year. It wasn’t until 1921 that the four movement piano version saw the light of day. It was dedicated and premiered by Selva a year later at the Salle Pleyel in Paris. The pieces are titled: Stamboul; Le Phanar; Eyoub and Galata. Stamboul is solemn and haunting, and when arpeggiated chords make an appearance, they confer a hypnotic quality to the music. Le Phanar makes a striking contrast, offering jazzy dance rhythms, which are breathtakingly frenetic. Eyoub is serene and wistful, whilst Galata ends the suite in a flurry of intensity.

The Nocturne No. 2 by Joseph-Guy Ropartz dates from 1916. Highly romantic and passionate, it demands a formidable technique from the pianist. Its ABCBA form transports us on a turbulent emotional journey, rich and complex. At the end, Ropartz alludes to church bells as the music settles into the serenity of the night.

Cécile Gauthiez’s Fête béarnaise of 1921 is here receiving, together with Pierre de Bréville’s Stamboul, its world premiere recording. The work makes good use of jaunty, bouncing rhythms to support a light-hearted frolic. Though only 4 minutes duration, it’s a delightful miniature with a smile on its face.

Two years later in 1923 Georges Migot composed his three movement Le Tombeau de Dufault, jouer de luth. The three pieces are titled Prélude, Elégiaque and Décidé. The composer had a passion for Renaissance and lute music. The work imitates lutes, and the score is unusual in that there are no bar lines, so there’s a feeling of improvisation throughout. The booklet notes tell us that “Fantasy and audacity combine here”.

Vincent d’Indy’s Thème Varié, Fugue et Chanson, Op.85 (1925) is a substantial and resourceful work. The theme is complex and is followed by seven contrasting variations, the final one leading into a four-part fugue. The work ends with a Chanson, where the mood is one of optimism, exuberance and jubilation. The composer dedicated this accomplished score, together with his Sonata in E of 1907, to Selva, who premiered it in Lyon in January 1926.

Diane Andersen is a marvellous advocate for these intriguing and alluring works. She performs them with commitment, power and passion. The booklet notes are by Damien Topp and have been translated into English by MusicWeb’s Ralph Moore.

Stephen Greenbank

Availability: Ciar Classics