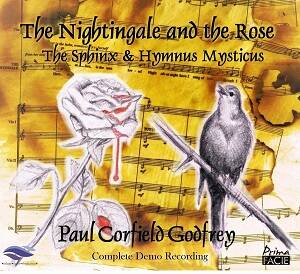

Paul Corfield Godfrey (b.1950)

The Nightingale and the Rose – An operatic fable for nine voices, chorus and orchestra

The Sphinx for baritone and orchestra

Hymnus Mysticus for soprano, baritone, chorus and orchestraVolante Opera Productions

EastWest Software Quantum Leap Symphonic Orchestra

rec. 2022

Prima Facie PFCD197 [61]

Paul Corfield Godfrey is a distinguished writer for this site … and the present disc also shows him as composer. Perhaps that should be the other way around.

He was born in London and now lives in Wales. He has studied composition and conducting with Alan Bush and David Wynne. There are many works to his name, including four symphonies, orchestral, chamber and instrumental scores, songs, choral works and operas.

Not lacking in ambition and with the ‘reach’ to match, his very grand stage works include a cycle of operas, “epic scenes” based on Tolkien’s Silmarillion. Prima Facie has recorded those scenes across ten discs (review ~ review ~ review) and they are now – or soon will be – available to purchase from the label, either individually or as a complete cycle. If the books remain ploddingly and forbiddingly indigestible, sold off the back of The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit, Godfrey’s operas have redeemed them with impressive brilliance, making them far more accessible, magical, poetic and fabulous.

He has written many other non-Tolkien pieces and some of these are presented on the present disc. This runs slightly over an hour and most of the disc is made up of a fulsome setting of Wilde’s The Nightingale and the Rose. The other two works are quite brief. All three of these pieces set words to music. For two of them the author is Oscar Wilde (1854-1900) and the third, Hymnus Mysticus, is Aleister Crowley (1875-1947). These are unfashionable choices but the music rises above the trammel of fashionable ephemera.

Wilde’s words have been set, or have inspired works, by numerous composers including Arthur Benjamin, Alexander von Zemlinsky, John Alden Carpenter, Malcolm Williamson, Richard Strauss, Henry Hadley, Charles Griffes, Geoffrey Bush, Bernard Herrmann, Jacques Ibert, Prokofiev, Vassilenko and Lutyens.

Godfrey’s Wilde setting – The Nightingale and the Rose – An operatic fable for nine voices, chorus and orchestra – is the major work here. It’s an ambitious piece for which the word ‘fable’ (or fairy tale) seems small in proportion to what we hear, but it was Wilde’s designation for the story. In any event ‘fabulous’ seems a better fit for what we hear in a long piece running to about 35 minutes across 14 tracks. This in itself eases analytical listening and might also aid musicians in learning a piece for performance … and pleasure … or both.

The muted ‘tizzing’ rattle of the tambourine begins and ends this piece. This sampling sound strikes a mildly false note but is soon gone and what follows is more convincing … more authentic sounding. The ideas played out build a prelude to what follows. Godfrey deploys Wilde’s words to good effect. There are lots of words but they are nicely rounded and emoted by the two solo voices who inject personality as if they believed in the piece. Along the way we become aware of Godfrey’s skills with colourful ideas and orchestration. For example track 5 has some enchanting Baxian harp decoration. In the, at first, purely orchestral Interlude (track 9) the music muses quietly outlines an idea that is reminiscent of Pavane pour Une Infante Défunte but in a small space of time builds it to the high places – the same ecstatic regions occupied by Delius’s A Song of the High Hills. More instrumental treatment emerges at tr. 12 – dignified and yet with a payload of tragedy. The overall sound of this piece might be compared with Delius’s Idyll – Once I passed through a populous city or Frank Bridge’s opera A Christmas Rose and the pre-Great-War orchestral poems. The words are sung feelingly: take track 3 where the vocal parts take a heightened romantically-melting course. The ecstatic intertwining of the soprano and baritone voice in that track and the next one are a fine way to sample the piece. The soprano in track 5 ascends to a coloratura stratosphere. I should add that the choir sings with much delicacy and passion. While the words of the final section suggest that Love plays its ‘victims’ false (“What a silly thing Love is!”) Godfrey’s music suggests that he remains unconvinced that love is a lost cause.

The shortest piece here, at just 4:30, is the buxomly upholstered, Wilde-inspired, The Sphinx. This flourishes some Stanford-like derring-do in the words “away to Egypt” and with it a sense of winged victory. Wilde’s words would have been the sort of high-flown poesy that would have gripped Cyril Scott and which did, in fact, draw a song-cycle from Granville Bantock.

Hymnus Mysticus is – across a variety of styles – in the same exalted mystical realms as Holst’s Hymn of Jesus and Ode to Death, Cyril Scott’s big choral piece The Hymn of Unity, Friedrich von Hausegger’s Natursinfonie or Martinů’s Epic of Gilgamesh. Godfrey’s baritone comes across as declamatory – and once or twice just a bit wobbly. Going by the words channelled his way, that approach is quite consistent with Crowley’s intentions. The soprano has a sweet high-piping voice with just a tinge of harshness. The course of the work suggests the hieratic with the trumpet calling out piercingly. Towards the close an organ enters which well serves the music’s pantheistic hymnal qualities in defiance of the instrument’s ecclesiastical associations. A nice balance is struck between voice and orchestra; one of the strengths of the composer being closely associated with the finished recorded product.

Almost the first thing that strikes you as you play this CD is that despite what we hear being the product of an App the resulting sounds evince a remarkable approach to concert hall realism. There are some moments when a synthetic quality comes to the surface but in general the effect is very good indeed. The attractions of this facet of the project are underlined by the skilled and caring contrivance of the sound-stages for voices and orchestra and techniques for doubling single voices to produce convincingly the sound of a massed choir. Some real thought has gone into this and musical rewards are reaped. The performances here might well be good representations of what Godfrey wanted; only the composer will know for sure. They seem to me to smoulder with conviction.

It is clear from the evidence of our ears that the techniques of electronically rendering orchestral sound have come on by ‘leaps and bounds’. We are long past the days (and I do not decry them) when people like Bhagwan Thadani was introducing us to recordings of the concertos and symphonies of Bortkiewicz – discs now superseded by Hyperion’s and Chandos’ recordings made with real forces. In the same line a friend produced for me a playable sound file from the full score for Joseph Holbrooke’s The Pit and the Pendulum long before the Dutton project.

The disc booklet generously squeezes in the full sung texts with profiles of the composer, the soloists (all on the strength of Welsh National Opera) and the opera company. There’s an admirable note underscoring that Godfrey has relied on sampling to ‘create’ the choir and orchestra. The two solo voices, operatic but not blowsy or vibrato-dominant (or only rarely), were each recorded individually and in isolation. All recording projects, including real life choirs and orchestras, are exercises in technical skill and the simulation of a concert experience. ‘By their fruits shall ye know them’ and what we hear in this case is overwhelmingly believable and a listening pleasure. The purpose of this “demo recording” is to get Godfrey’s music heard. This aim is achieved.

Godfrey and Volante have shown the way forward for other similar projects. Examples of other music that would benefit from this treatment abound. I think complex and extravagant works such as those by Sam Hartley Brathwaite (his two little orchestral sketches), Roger Sacheverell Coke, Stanley Wilson (A Skye Symphony), Cecil Gray (the music-dramas including The Trojan Women and Deirdre), Granville Bantock (The Great God Pan), Robert Bryson’s two symphonies (1908, 1928) and Rutland Boughton (Arthurian operatic cycle) to mention a few. A vain hope; but I do hope.

Godfrey’s qualities are to be admiringly appraised and they vie with his modesty in not featuring his name on the CD cover – just the names of the works. As to layout, The sphinx is in one track while Hymnus is in six; The Nightingale is in 21. No date is given for any of the three works which is a pity. I suspect they hail from the last two decades although they are broadly in a style that in effect re-sets the word ‘contemporary’ to a ‘brand’ of more romantic and lush impressionism.

All of that said, there is intrinsic stimulation, pleasure and delight to be had in these three works from Paul Corfield Godfrey.

Rob Barnett

Help us financially by purchasing from

Performers

The Nightingale and The Rose

Cast (in order of singing):

The Student: Simon Crosby Buttle (tenor)

The Nightingale: Angharad Morgan (soprano)

The Green Lizard/The Yellow Rose Tree: Julian Boyce (baritone)

The Butterfly/The White Rose Tree: Helen Greenaway (mezzo)

The Daisy/The Red Rose Tree: Jasey Hall (bass)

The Beloved: Sophie Yelland

Chorus: Paula Greenwood; Emma Mary Llewellyn; Sophie Yelland; Helen Greenaway; Simon Crosby Buttle; David Fortey; Julian Boyce; Jasey Hall

The Sphinx

Julian Boyce (baritone)

Hymnus Mysticus

Emma Mary Llewellyn (soprano)

Julian Boyce (baritone)

Chorus for Sphinx and Hymnus: Angharard Morgan; Emma Mary Llewellyn; Sophie Yelland; Helen Greenaway; Simon Crosby Buttle; David Fortey; Julian Boyce; Jasey Hall