Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827)

Symphonies Nos 1-9

Kate Royal (soprano), Christine Rice (mezzo-soprano), Tumoas Katajala (tenor), Derek Welton (bass-baritone)

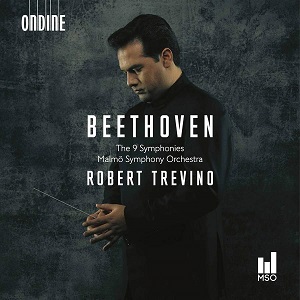

Malmö Symphony Orchestra and Chorus/Robert Treviño

rec. live, October 10-19, 2019, Malmö Live Konserthus, Sweden

Ondine ODE1348-5Q SACD [5 discs: 350]

“We’re at the crossroads at this music. Do we perform music like the old masters? Like Furtwängler and Karajan? Like the early music movement with Nikolaus Harnoncourt and John Eliot Gardiner? I’m an admirer of both of these aesthetics and it’s a testament to Beethoven’s ideas that the music can withstand such absolutely different treatments and still speak to us true of its intent. It’s important for every generation, every orchestra, every country to make their statements at different moments with this music. It catalogues a way of thinking, a way of playing and a way of seeing the world. And the world now in 2020 is very different to what the world will be in 2030 and also very different from the world of 1770 when Beethoven was born.”

In a refreshingly honest and unpretentious interview from the accompanying booklet, the Texan-born, Mexican-American conductor, Robert Treviño, introduces his recordings of the Beethoven Nine Symphonies with the above statement. Recorded in chronological order, live in four concerts over two weeks (although you’d be hard-pressed to detect the presence of the eerily quiet audience who do not applaud), since it was released in time for the 250th anniversary of the composer’s birth in 2020, Treviño has created quite a stir, with further highly-praised releases of Ravel’s orchestral music (review), as well as American orchestral music (review), so this review is something of a corrective, as this cycle has not received quite as much attention as it perhaps deserved and would have done had it been released now.

It is certainly something of a statement to make for a conductor in his mid-thirties to open his account with both a new label (Ondine) and a new orchestra, the Malmö Symphony Orchestra – of which he became the Chief Conductor in 2019 – with this music. It would also be easy, as some commentators have already done, to conclude that Treviño’s way with Beethoven is merely a hybrid of one his mentors, David Zinman, and Daniel Barenboim, whom he consulted with regard to performing Beethoven’s symphonies. Yet for someone still so young (he was born In 1984), Treviño seems supremely aware of and knowledgeable about the Beethoven performing tradition (at least on recordings), and has his own very distinctive ideas of how the music should go, ideas which appear to be rooted in the traditional mainstream of Beethoven interpretation with a nod towards the historically-informed movement and none of the eccentricities displayed recently by Thielemann in his cycle (with the Vienna Philharmonic, see review) who in turn is as innocent as a parish priest when compared to Mikhail Pletnev, whose cycle with the Russian National Orchestra (review) proves that the thin line between genius and madness is very slim indeed.

In the event, I have found it most enjoyable to become acquainted with this cycle, if only for purely musical reasons rather than encountering any daring interpretive insights. For example, Treviño genuinely observes Beethoven’s instruction of adagio for the introductions of the opening movements of the First, Second and Fourth Symphonies, unlike more recent ‘historically-informed’ practitioners who seem to aim to perform them more swiftly so that they become more of a piece with the rest of the opening movements. This is not to suggest that Treviño leads performances of the allegros that are sluggish or lacklustre, just that he avoids the pitfall of making the music sound fast, faster and even faster, something I feel could be levelled at Riccardo Chailly in his recording of the complete cycle; he seems to be hell-bent on breaking land speed records during his traversal with the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra (review). Curiously – and also against current trends – his fiddles are not divided, which may disappoint some, but all repeats are observed. Throughout, the Malmö players are on top form and the sound by Ondine is supremely well-balanced and clear, if perhaps lacking a little warmth, which I am attributing to the presence of an audience in the hall rather than any failure on the part of the engineers. For this review, I was given the hard-copy box set, which contains all the symphonies in chronological order, two per disc, with the Ninth on its own as the final fifth disc, all contained within the now commonplace cardboard sleeves. Sampling all formats revealed little difference in sound quality.

Apparently, Treviño conducted Beethoven’s earliest symphony for the first time when he was fourteen years old and his performance is one of youthful high-spirits, as is the Second Symphony, where he is careful to promote a grander execution of the music, with a leisurely Larghetto that just about avoids sounding bland thanks to the warmth of the orchestral response. I am slightly less convinced by the Eroica, however – not with the second movement’s funeral march, as hushed and intense as any, but more with a first movement which seems to aspire to a grandeur that the decision to opt for the trumpets continuing their phrases in the coda suggests, but elsewhere is not quite achieved. The last two movements showcase the Malmö woodwinds, who are clearly a superb group, with the finale’s second variation assigned to solo strings, as with Zinman, except more self-consciously executed.

A lack of grandeur can clearly be levelled at the Fifth Symphony too, in an otherwise tough and propulsive performance, satisfying in its own way, but comparison with Carlos Kleiber’s famous account with the Vienna Philharmonic, or more recently, Manfred Honeck’s with the Pittsburgh Symphony, demonstrates similar interpretive ideas taken to a level or two higher than that achieved by Treviño and his players here. On the other hand, and especially next to Honeck’s somewhat overthought account of The Pastoral released last year (review), Treviño demonstrates how a simple approach with much amore can reap infinite dividends in a way that Honeck’s foot stamping players singularly do not. In particular, the Malmö woodwinds once again shine gloriously, especially in their imaginative shaping of the bird calls during the Scene by the Brook and the whole symphony receives an exceptionally fine and radiant performance that is a match for all except the very best in the catalogue. Similar conclusions can be drawn with the performance of the Fourth Symphony in this cycle, where the woodwinds shine and the Adagios of the opening and the second movement are lovingly etched.

According to the booklet, the final movement of the Seventh, played after the barest of breaks following the third movement, was taken at a faster tempo than was planned and rehearsed, an example of how the ‘grace of the moment’ can sometimes attend live performances. There is no doubting the excitement, nor that the Malmö players are more than equal to the task, but once again I was left wondering if the performance was straining to be grander than it was, something which could have been achieved perhaps with a larger string choir.

The performance of the Eighth is, however, a slight disappointment, ironically, on this occasion, because of the interventions of the conductor. Treviño clearly sees the work as perhaps a step back after the cosmic dynamism of the Seventh, rather than one forward towards the mighty Ninth as with Karajan, for example. He would not be the first conductor to take this approach, but after a fine opening and ensuing first movement, all the good work is undone by his decision to insert a ritartando for its closing bars, thereby undermining Beethoven’s own humorous ending (ironically, the conductor makes the observation in the booklet about Beethoven’s humour and the importance of timing to bring it out). A faster than usual third movement is followed by a finale which is distinguished by the interplay of the various instrumental groups in the orchestra, but just falls short of being very good on account of a certain lack of character.

The Ninth neatly displays all the strengths and weaknesses of the set. The first movement is propulsive and strong, typical of the cycle as a whole, where interpretive points are achieved by use of phrasing and articulation, rather than rubato or undue underlining. However, once more I rather felt Treviño’s approach warranted greater majesty than achieved in these performances, not least with the great central climax of the movement that is approached as if forewarning the end of time, but then falls short with the cataclysm somewhat underplayed. The Scherzo has a dazzling energy and is distinguished by the timpanist who varies his repeated salvoes with much imagination; perhaps surprisingly, Treviño eschews the traditional brass reinforcements that you may have expected after observing them at the end of the opening movement of the Eroica, yet the trio is sweetly consoling, rather than driven as with many historically-informed performances as well as – you may be surprised to read – Schuricht, in his fine cycle from Paris, originally on EMI. Likewise, the Adagio is more leisurely than perhaps we have grown accustomed to over the years: sweetly lyrical, but lacking the last ounce of concentration to sustain it and only just about avoiding the charge of blandness. In the final movement, the seventy-five-member chorus is slightly backwardly balanced and can sound strident in the loudest tuttis, while the soloists suffer a similar fate. They are a decent, if run-of-the-mill group, since long gone are the days when record companies rolled-out their star singers for their recordings of the Choral Symphony; however, at least they don’t sound as if they are performing a Mozart Singspiel as with Honeck’s group in his disappointing recording from 2019 (review). That said, Treviño leads a fine performance distinguished by sensible tempos and a unified vision which, if it creates only an impression of general excitement rather than cosmic rejoicing, is still ultimately supremely satisfying.

Overall, in spite of my caveats, this is a consistently fine cycle, only falling short in comparison with the absolutely greatest; it achieves the conductor’s stated ambition of marrying the great tradition of this music with modern thinking in performances all of which consistently exhibit style and flair, and sound freshly minted. On this evidence, Robert Treviño exhibits all the hallmarks of becoming a great Beethoven conductor and as such, this set will provide much satisfaction to anyone acquiring it. It is Beethoven for the 2020s indeed.

Lee Denham

Help us financially by purchasing from