Déjà Review: this review was first published in May 2001 and the recording is still available.

Ralph Vaughan Williams (1872-1958)

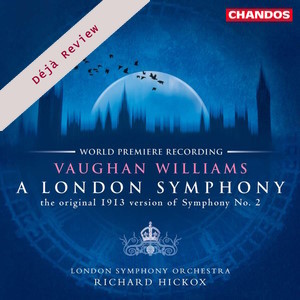

A London Symphony (Symphony No. 2) (original 1913 version)

George Butterworth (1885-1916)

The Banks of Green Willow

London Symphony Orchestra/Richard Hickox

First recording – Vaughan Williams

Chandos CHAN9902 [68]

This is such an important release that the usual summary reserved for the very end of the review must, on this occasion, appear at the beginning – if you have any interest in the music of Vaughan Williams whatsoever, this is an almost mandatory purchase. It will give enormous pleasure to all. But to those who already love VW’s nostalgic and uplifting portrait of London before the onset of the Great War, it will come as a particularly exciting surprise; rather akin to finding a hidden and forgotten suite of rooms behind a disguised door in the house one has lived in for many years.

After the initial performances of 1914/15, Vaughan Williams began to re-evaluate his compositional style and, by the end of the war, he was fast moving away from the expansive programmatic structure of his first two symphonies towards the more concise format of his third A Pastoral Symphony. He began a three stage process of tinkering with his symphony; in 1918, 1920 and 1933, leading to the 1936 publication of the work as we know it today. The effect of the war was great for many composers most of whom changed their styles in a similar fashion to Vaughan Williams. Already in 1918 he was making cuts stating that he now preferred to refer to the work as a ‘Symphony by a Londoner’. He went so far as to tell Bernard Herrmann that the middle of the symphony contained ‘some horrible modern music – awful stuff’. In effect he was distancing himself from the descriptive elements of the work and claimed ‘The music is intended to be self-expressive, and must stand or fall as absolute music’.

Yet the London Symphony remained a favourite of VW’s throughout his life and surely his references to the Westminster Chimes and the slow movement’s ‘lavender cry’ as ‘accidents’ must have been tongue in cheek. He cut a great deal from the original version, but not, significantly, those two particular elements. Indeed the descriptive nature of the work could never really be expunged, for when his great friend George Butterworth had originally suggested a purely orchestral symphony to follow the Sea Symphony, VW had dug out, altered and expanded a tone poem he was then working on.

So, the original version of the London Symphony was really part of that pre-war world which stood as the final flowering of the ‘fin de siècle’, rather than demonstrating any sign of coming to terms with the musical changes being wrought by Schönberg. Butterworth himself had originally had doubts about the last movement, but on hearing the first performance wrote to VW: ‘the passages I kicked at didn’t bother me at all, because the music as a whole is so definite that a little occasional meandering is pleasant rather than otherwise’. Those first performances were extremely well received and friends such as Arnold Bax and R.O. Morris made it clear that they regretted the ensuing cuts.

This is therefore a version of a much-loved symphony that was altered against the advice of friends, not as a consequence of public disapproval nor in response to any concern about the viability of future performances. The first movement Vaughan Williams left untouched. Richard Hickox, who, with Chandos Records, deserves the highest commendation for persuading the composer’s widow Ursula Vaughan Williams to allow this recording (but not, sadly, future live performances) can therefore be directly compared with other interpreters. The acoustic of All Saints, Tooting, London is pretty reverberant (Hickox also recorded the Sea Symphony there with the Philharmonia) so the tempo is naturally on the slower side. But the impact is terrific. Chandos’s sound is resplendent, superbly balanced allowing, for example, the all-important parts for percussion and harp (even when playing pianissimo) to come through clearly. The ending is particularly grand.

Stephen Connock, the Chairman of the Ralph Vaughan Williams Society, provides excellent notes pointing out the passages that were cut by VW and ‘restored’ in this recording. Rightly he enthuses over the fact that a substantial amount of unheard but high quality VW is now available for the first time on CD. He claims an extra twenty minutes is now uncovered but I feel this to be a slight exaggeration – even at Hickox’s tempos it’s much nearer fifteen. Nevertheless throughout the remaining three movements one hears marvellous stretches of music for the first time, several of them second cousins to what one already knows, but even more of them are completely unexpected. In particular, certain folk-music elements and related passages re-emerge as wonderful discoveries giving full credibility to Bernard Herrmann’s contention that ‘the most original poetic moments in the entire symphony’ were subsequently lost in the revisions.

Vaughan Williams cut about a third of the music from each of the last three movements. In the finale there is a previously unknown Andantino section (later briefly reprised just before the Westminster Chimes) which represents, perhaps, the most interesting and important of all the restored passages. Scored for winds and strings, it will greatly surprise those – like myself – who had previously felt that the 1936 version was incapable of improvement. Indeed, although Michael Kennedy, in his supplementary note, is right in saying that the final version has to be recognised as the true ‘London Symphony’ – according to the composer’s wishes – it must also be accepted that the symphony in its original version remains an equally superb work, even at its length of over 61 minutes.

The brief fill-up is an ideal coupling, composed in the same year as VW finished his original version of the London Symphony. It is extremely well performed; the slightly sour sounding oboe is more than made up for by beautifully played solos from the flute and first violin.

As I said at the start – mandatory.

Simon Foster

This CD contains the world première recording of Vaughan William’s original 1913 version of A London Symphony. The composer set about revising the work in 1918, 1920 and 1933 and it is this last version which has been widely performed and recorded ever since. The new Chandos disc gives us a rare and very welcome opportunity to hear the composer’s original ideas for his own favourite symphony.

The first movement has no new material in it, but Richard Hickox adopts a significantly steady tempo throughout (clocking in at 15:04 as opposed to Sir Adrian Boult’s 14:23 in his 1971 recording for EMI (CDM 7640172) – and Boult’s version sounds by no means rushed). Conscientious and thoughtful musician as he is, Hickox has clearly considered the 1913 version’s additions deeply and how they affect the proportions of the symphony as a whole. His broad Lento introduction makes a convincing counterweight to the significantly longer Epilogue at the end of the work. The first movement responds well to Hickox’s sensitive direction: climaxes are carefully prepared and the more reflective moments in the development section are beautifully realised.

The Lento slow movement now contains a highly characteristic Elizabethan-style motif (7’17”), a welcome addition to the symphony. Lengthy extra passages for solo oboe, viola and horn, on the other hand, distend the movement and disrupt its symphonic flow. Beautiful though these solos are, one can’t help conclude that RVW left enough in his revised version and the extra ones succeed in losing the symphonic plot. A brief passage peculiar to the 1913 version near the end of the movement (14’09”) with fragmentary solos over a shimmering descending tremolo string line is strikingly Mahlerian (particularly reminiscent of the magical falling string tremolos which introduce the posthorn solos in the Scherzo of Mahler’s Symphony no 3).

The Scherzo, taken at a sparkling pace, gains extra material in its second half and now seems to outstay its welcome slightly before the splendidly cocky and gawky Trio makes its belated appearance. The original version adds a nostalgic, wistful second Trio (5’55”) and the Scherzo ends more satisfyingly in the original version, with wispy echoes of its airy main theme disjointed and deconstructed.

The Finale gains much in the 1913 version, the violent contrasts of mood better prepared and less bluntly juxtaposed than in the 1933 revision. After an impassioned central climax, the ghostly return of material from the first movement (10’44”) is a welcome touch before the extended Epilogue which becomes almost a whole movement in itself, kicking in at around 10’58” and thus lasting for nearly eight minutes. The weight of the symphonic argument has been successfully transferred to the Finale and Hickox and the LSO bring a special intensity and nostalgic regret to the symphony’s unforgettable parting vision of a lost Edwardian world so soon to be blown apart.

This première is a major achievement. The recording is up to Chandos’s usual high standards and the booklet contains two excellent articles by Stephen Connock, chairman of the RVW Society and Michael Kennedy. The performance is marvellously sure-footed and persuasive, Hickox never overplaying the new material, but remaining clear as to the natural climaxes and tensions of each movement. It is a treat to have a choice of versions in this great symphony but despite the many incidental beauties of the original version, the 1933 revision must remain supreme for me because it is more rigorously symphonic. The 1913 version with its many discursive solos and additional subjects frequently makes the work sound more like a cycle of four tone poems than a closely argued, organic symphony (incidentally the composer’s first sketches for the work were for a symphonic poem about London). The 1933 revision is more focused and less given to Baxian purple patches (no wonder Bax liked the original version so much: in its magical effects, nostalgic asides and elongated Epilogue it’s practically a blueprint for a Bax symphony!). However, the new material is all prime RVW and other listeners will react differently and may well end up preferring the composer’s original thoughts. I urge anyone with an interest in British music to purchase this excellent disc. The committed and moving performance of Butterworth’s tone poem is an added incentive, as if one were needed. Highly recommended.

Paul Conway

Help us financially by purchasing from