Nikolai Miaskovsky (1881-1950)

Cello Sonata No. 1 in D major Op. 12 (1911)

Cello Sonata No. 2 in A minor Op. 81 (1938)

Cello Concerto in C minor Op. 66 (1944)

Anatoly Liadov (1855-1914)

Prelude, Op.11 No.1 (1885-86)

Mazurka, Op.11 No.3 (1885-86)

Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov (1844-1908)

Serenade, Op.37 (1893)

Raphael Wallfisch (cello), Simon Callaghan (piano), Janáček Philharmonic Orchestra/Łukasz Borowicz

rec. 2020, House of Culture, Ostrava; Wyastone Concert Hall, Wyastone Leys, Monmouth, UK

cpo 555 420-2 [76]

This disc is devoted to Miaskowsky’s popular Cello Concerto and his two cello sonatas, and as a bonus we are given the pieces by his teachers at the St Petersburg Conservatoire, Lyadov and Rimsky Korsakov. It is ironic that a composer of twenty-seven symphonies should gain fame for works written for the cello mostly because the great cellist Rostropovich proselytised the Second Cello Sonata as an obligatory piece for his students.

Following his graduation from the Conservatoire, Miaskowsky composed the First Cello Sonata in the woods near Moscow in the summer of 1911. Throughout his life, nature was the source of his finest compositions, and this piece hints at the idiom that would characterise not only his later cello works but his symphonic masterworks. The harmony of the cello draws one into the deeply philosophical core of the sonata. The beautiful first idea is introduced, with great sensitivity, by Callaghan and Wallfisch, and there is a sense that the musicians are playing this for the first time and of our sharing in the musicians’ enjoyment of this music. The recording is as if one is sitting next to them, with marginally more balance given to the piano. I still find it strange that this late Romantic sonata is not heard more often, as it is a wonderful entry into the composer’s sound world.

The Cello Concerto is his most popular orchestral work and was recorded no fewer than three times by Mstislav Rostropovich. It is dedicated to the latter’s teacher Svyatoslav Knushevitsky, who gave the world premiere in 1945. The two-movement work opens Lento ma non troppo with a lengthy entry by the orchestra, and the cello enters elegantly, and we hear wonderful entries from the woodwind, stressing the late Romanticism of the piece. The cadenza in the first movement is played sensitively by Wallfisch, bringing out all the harmonies in the autumnal shades characteristic of the composer’s twilight years. The mood of melancholy sways powerfully with the eloquent strings of the Czech orchestra well directed by Borowicz. There is a measure of spontaneity, as if we were listening to a live performance.

The second movement takes the form of a rondo, Allegro vivace, which has two passages played at a deliberate rhythm, as distinct from the scherzo-like section. There is a beautifully poised cadenza heralding a reprise of themes from the first movement and a stunningly performed coda. I would not recommend this recording as a first choice, as that would be the recordings by Rostropovich and Sargent with the Philharmonia on Alto and Marina Tarasova on Olympia.

Despite the popularity of the Cello Concerto, the Second Cello Sonata is the most recorded and performed of all the composer’s works, not only for its charming late Romanticism but for the stalwart advocacy of its dedicatee Rostropovich who gave the first performance in 1949. The piece dates from when the composer was suffering from cancer. The expansive first idea in the opening Allegro moderato is heartfelt and there is a freshly expressed exhilaration here, distinctive of Miaskowsky’s late works. The Andante cantabile is lyrical and there is a beautifully expressed poetry on the piano picked up magically by Wallfisch. The Finale Allegro con spirito conveys a sense of life and energy in the stimulating playing by both musicians. Again, one senses a spontaneity in the playing which is captured well by the recording.

The three brief pieces by Lyadov and Rimsky Korsakov reveal no association with Miaskowsky’s music apart from accentuating brief cameos of richly inventive creativity in which Lyadov excelled in his orchestral pieces, while lacking the more significantly expansive nature of Rimsky Korsakov. All the three pieces were originally for solo piano yet were arranged for cello by the composers as encore pieces, and are sensitively performed and recorded.

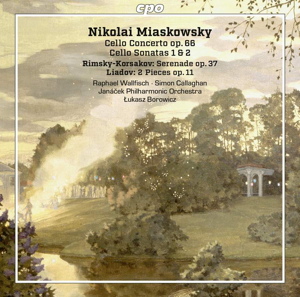

There is a 24-page booklet with texts in English and German about the music and biographies of the performers with a colour photo of Raphael Wallfisch, a black and white photo of Miaskowsky and of the musicians and the cover is adorned by an illustration of Konstantin Somow’s 1922 painting, ‘Fireworks’.

Unfortunately, the notes by Patrick Zuk are deceptive in the claim that Miaskowsky is unpopular because of his ‘lack of surface appeal’ and the ‘cloud of ideological opprobrium created by Soviet commentators’. Miaskowsky’s music lost its appeal (as did that of Shostakovich and Prokofiev) owing to the Cold War and the break in cultural exchanges. The essay overlooks his work as a music critic and teacher of three generations of composers and ignores the fact that he spent twenty years writing an opera based on Dostoyevsky’s ‘Idiot’, and ‘King Lear’. Despite these flaws, this release will interest those who wish to hear a collection of all Miaskowsky’s cello works in outstanding performances faithfully recorded.

Gregor Tassie

Previous review: Jonathan Woolf (April 2023)

Help us financially by purchasing from