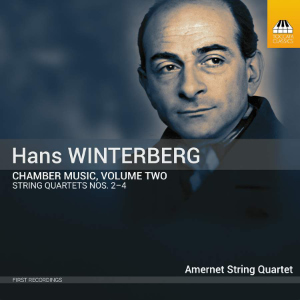

Hans Winterberg (1901-1991)

Chamber Music – Volume Two

String Quartet No.2 (1942)

String Quartet No.3 (1957)

String Quartet No.4 (1961)

Amernet String Quartet

rec. 2022, Jeffrey Haskell Recording Studio, Fred Fox School of Music at the University of Arizona, Tucson, USA

Toccata Classics TOCC0683 [64]

In volume 1 of Toccata’s chamber music series devoted to Czech-born Hans Winterberg’s miscellaneous works (review), I touched very lightly on his biography as it’s a complex matter best learned from Michael Haas’s extensive booklet notes. The second volume in the series focuses more precisely than the first, and that focus is on his string quartets. No.1 is missing. It was called a ‘Symphony for String Quartet’ and though it was, as Haas tells us, long believed lost, it turned up after the remaining three quartets had been recorded.

No doubt it will make an appearance later on in the series. For now, things start with the Second Quartet of 1942, written at the time when Winterberg, a Jew, was working as a slave labourer near Prague. This is a complex work, as are all Winterberg’s quartets, its opening falling theme reflecting a dispiriting narrative of skittering, tremulous, texturally ambiguous writing; there’s little comfort to be found, understandably. The central movement’s Passacaglia emerges after an indeterminate, stark introduction, the music seemingly dreamlike and unmoored. It’s an emotive state that continues into the finale, uneasy, faltering, indeterminate and increasingly melancholy.

Winterberg was a sophisticated, forward-looking composer who had mastered the use of polyrhythms and poly-textures. By the time of the Third Quartet in 1957, his canvas was larger and his language more complex and wide-ranging. One doesn’t have to agree with Haas that this is ‘one of the great quartets of the twentieth century’ to acknowledge the many challenges it sets listeners or the rewards that can be found in it. The constant changes of metre in the first movement allow an unremitting alternation of tempi, the music emerging as a study in rhythmic displacement, full of sonic interest, from fast running figures to pizzicati and constant variation of texture. If, however, you prize tunefulness you’ll be searching in vain. There are restless, rocking figures in the slow movement, taut undercurrents that never allow the music to settle until the dynamic March theme of the finale arrives tinged with intensity, even implacability.

Winterberg’s Fourth Quartet followed in 1961 and with it a return to the relative compression of the Second Quartet. The music starts with pizzicati but has a decided lack of ‘centre’ and there’s a sense of evanescence that proves increasingly troubling. Sonorities are quizzical and curious but the return of the pizzicati indicates that the opening gesture is one subject to subsequent variation. The central Nocturne has no sense of perfume about it, whilst the finale circles around, though does allow an aromatic first violin role. Acerbic and rough in places, the music reaches a fervent pitch, to end decisively. This is apparently not simply the first recording of the work but the first ever performance. The Second and Third Quartets are also world premiere recordings so there is nothing against which to measure the performance of the Amernet String Quartet though they seem to generate all the necessary sonic variety to bring these works to life.

Winterberg lived another three decades but wrote no more string quartets. They are hard to describe. Haas mentions Janáček in the context of the finale of No.2 but I have to say I don’t hear it. The folk roots, also suggested, sound very remote – at least if we are considering the usual use to which Czech composers put folkloric elements in their music. Nevertheless, Winterberg’s individuality is consistent and imposing and reflective, surely, of the many cruelties and obstacles he faced.

The performances and recording are both excellent and Haas’ notes obviously beyond any reproach.

Jonathan Woolf

Help us financially by purchasing from