Déjà Review: this review was first published in April 2002 and the recording is still available.

Giacomo Puccini (1858-1924)

Tosca

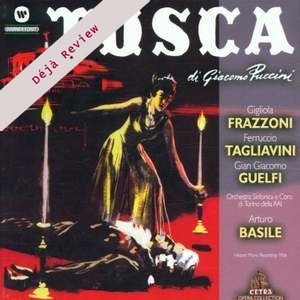

Gigliola Frazzoni (Tosca), Ferruccio Tagliavini (Cavaradossi), Gian Giacomo Guelfi (Scarpia), Antonio Zerbini (Angelotti), Alfredo Mariotti (Sacrestan)

Turin RAI Chorus and Orchestra/Arturo Basile

rec. 12 October 1956, Turin

Reviewed as Warner Fonit 857387479-2

Warner Fonit 2564698345 [2 CDs: 115]

The trouble with Fonit-Cetra LPs in the past was their impossibly shrill sound and poor pressings, with the result that they tended not to be taken in very serious consideration except for the rarer Italian operas which were unavailable elsewhere. I should add that I am speaking in general, not having heard the original of this particular set, but I am sure that some very good work has been done here. The forwardness of the voices remains endemic, but they are finely recorded with excellent presence and considerable dynamic range. And, if the orchestra is a little further behind than we would want today, it is in itself remarkably clear in even the strongest passages, and allows us to hear real Puccinian dolcezza in the softer moments. This recording now turns out to be as good as most others of its period, and I might add that it seemed even better on headphones.

The name which will first attract opera buffs is that of the tenor. Born in 1913, Tagliavini made his debut in Bohème in Florence in 1938 and established himself rapidly after the war, appearing at the Metropolitan in 1948 and Covent Garden in 1950. In 1956 he was at the height of his career (he retired in 1970). Though considered above all a tenore di grazia, he shows plenty of heft for a big Puccini role, the voice always firm and ringing, while he finds memorably honeyed tones for Qual occhio (Act I is generally notable for the lyricism it finds in odd moments sometimes passed over) as well as O dolci baci (during E lucevan le stelle) and the beginning of the duet O dolci mani. Since Tagliavini does not limit himself to singing the part exceedingly well, but is thoroughly inside it too, this is a performance which connoisseurs will need to have.

They will also be glad to have a rare recorded performances by Frazzoni, one of the several casualties of the total dominance of Callas on the Italian scene at the time she was making her career. Gigliola Frazzoni was born in 1927, is, as far as I can discover, happily still with us, and had made her La Scala debut in Andrea Chénier the year before this recording. She was noted for her Puccini and made a particular speciality of Minnie in La Fanciulla del West. The 1958 Decca recording might have been hers, for the original plan had been to record it in Milan under Antonino Votto, following performances in which Frazzoni had appeared, with Del Monaco and Corelli alternating as Johnson. However, Decca policy was to record all Italian operas automatically with Tebaldi and, irritated at Votto’s insistence on Frazzoni, recorded the work in Rome under Franco Capuana. (Votto was not Tebaldi’s greatest admirer; sometimes, while conducting her in the theatre, he could be seen surreptitiously stroking his chin, an Italian gesture which means “What a bore!”).

Frazzoni’s voice has plenty of the right body for the part, but above all she is right inside it, notably perceptive in the alternating moods of jealousy and trusting love in the first act, and fully equal to the demands, vocal and psychological, of the second and third.

Gian Giacomo Guelfi has a fine resonant voice. He is not as plainly malevolent as some Scarpias, but nor is he mannered; it is an excellent traditional assumption. I have listed the singers of two smaller parts, Angelotti and the Sacrestan, because one is immediately struck in their opening scene, as so often in a native Italian production, how much these little parts can contribute when well sung by singers fully able to give weight and meaning to their words.

The Italian Radio orchestras (of which only one now remains) have not always been world-beaters, but that of Turin, during Mario Rossi’s heyday in the 1950s, was the exception. Furthermore, in Arturo Basile they have a conductor in the Italian mainstream which seems to have died out with Gavazzeni. He catches the right ebb and flow, finds sweetness without indulgence, gives everyone space to sing their part without letting things become heavy, and shapes each act with a firm hand. Basile (1914-1968) worked regularly with the Italian Radio orchestras both in operatic and symphonic works and died in a car crash at no great age.

I have kept comparisons out of it so far, for this is a fine set with which to get to know the opera. However, I can hardly avoid mentioning that the Callas/Di Stefano/Gobbi/De Sabata recording of 1953, produced by Walter Legge, is one of the all-time great recordings. But, is it such a good idea to have only the classics on our shelves? If you don’t insist on state-of-the-art sound, this one is probably as good as any other before or since. You must have the Callas/De Sabata, of course, but there are plenty of reasons for having this one as well. Danilo Prefumo’s useful note gets an English translation but the libretto is in Italian only.

Help us financially by purchasing from

Christopher Howell