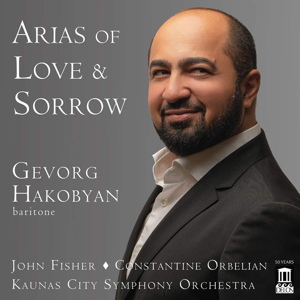

Gevorg Hakobyan (baritone)

Arias of Love and Sorrow

Kaunas City Symphony Orchestra/John Fisher & Constantine Orbelian

rec. 2018/2019, Kaunas Philharmonic, Lithuania

Sung texts with English translations enclosed

Reviewed as download from press preview

Delos DE3572 [55]

Armenian baritone Gevorg Hakobyan’s CV details an impressive number of prestigious opera houses where he has appeared and an equally impressive list of stage directors and conductors he has worked with. It says very little about his career, beyond the fact that in 2008 he was awarded both the Gold Medal and the First Prize at the prestigious First International Pavel Lisitsian Baritone Competition in Moscow, which seems to indicate that he then was at the beginning of his career. The sound of his voice gives me the impression of his being an elderly singer, but sounds alone can often be misleading. It is a sturdy baritone with tremendous power, but little nuance or flexibility of tone colour. Naturally, the choice of repertoire invites forceful singing, but a dozen high-octane arias makes for exhausting listening. Of course, one need not listen to the whole recital in one sitting, and there are indeed contrasts in the programming. It’s no run-of-the-mill programme of standard arias. Iago’s Credo is there of course, Gerard’s Nemico della patria¸ and Renato’s Eri tu, but Nabucco’s Dio di Giuda isn’t too often heard in recital and Michele’s monologue from Il tabarro even less. The Russians – Rachmaninov, Borodin, Rimsky-Korsakov and Tchaikovsky – are not heard every day, either, and most interesting of all are the two Armenian composers, Levon Khodja-Eynatyan and Armen Tigranian. Thus, the disc is well worth owning for the lesser-known works.

However, the singing of the standard arias also has merits. Hakobyan’s voice is firm and well-nourished – in spite of some over-generous vibrato at climaxes. He can certainly muster great intensity, and that, paired with his “charismatic acting“ mentioned in the notes, means that I am in no doubt that he can be very convincing on stage. The lack of nuances mentioned above, also has to be modified. He does find softer nuances in many places, most notably in the Ballo aria, where he sings O dolcezze perdute! O memorie/D’un amplesso che mai non s’oblia! (O lost sweetness! O memories of an embrace that made life divine!) mezzo-piano with great warmth. Here he suddenly shows his face, and I only wish he could find that expression more often. More regrettable is the sameness of timbre. All the characters seem to be the same person; Iago, for instance, should be quite different from Gerard and Nabucco – but that is probably a vain hope. Tito Gobbi had that capacity, but he was unique.

Concerning the Armenian operas there was of course a wish to create something nationalistic, which the Soviet authorities opposed. However, they allowed 19th century operas, and Armenian musicologist Alexandre Shahverdian and composer Levon Khodja-Eynatyan chose Tigran Chukhajian’s 1868 opera Arsace Secondo, which originally had a libretto in Italian, as their starting point, and rewrote and transformed the libretto into Armenian to suit communist ideals, and under the new title, Arshak II, it was premiered on November 29, 1945, at the Armenian Academic Opera and Ballet Theater in Yerevan. It was even awarded the USSR State Prize in 1946, and it is still performed in Yerevan. The music is in no way controversial.

Armen Tigranian composed Anoush a few years before World War I and in the 1930s he revised it to suit communist principles. It is the most popular opera in Armenian and is regularly performed. Like David Bek, Tigranian’s second and last opera, the music is easily accessible and prompts the wish to hear more of his music.

The Kaunas City Symphony Orchestra is by now a well-known quantity through a series of opera and recital recordings for Delos under their principal conductor Constantine Orbelian. This time, he shares the podium with John Fisher, and there is no information about who conducts what. The playing, however, is excellent and the quality of the recording is, as always with Delos, first class. I can’t pretend that I am completely sold on the singing, but it is honest music making without the last element of frisson and the repertoire is interesting.

Göran Forsling

Help us financially by purchasing from

Contents

Giuseppe Verdi (1813–1901): Otello

1. “Vanne . . . Credo in un Dio crudel” (4:39)

Umberto Giordano (1867–1948): Andrea Chénier

2. “Nemico della patria” (4:26)

Levon Khodja-Eynatyan (1904–1954): Arshak II

(Inspired and loosely based on an opera of the same name by Tigran Chukhajian)

3. Arshak’s Arioso (2:36)

Giacomo Puccini (1858–1924): Il tabarro

4. “Nulla! Silenzio!” (3:09)

Sergei Rachmaninoff (1873–1943): Aleko

5. “Ves’ tabar spit” (5:45)

Giuseppe Verdi: Nabucco

6. “Son pur queste mie membra . . . Dio di Giuda (4:05)

Giuseppe Verdi: Un ballo in maschera

7. “Alzati, là tuo figlio . . . Eri tu che macchiavi” (5:47)

Alexander Borodin (1833–1887): Prince Igor

8. “Ni sna ni otdycha izmuchennoj duse” (6:46)

Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov (1844–1908): The Tsar’s Bride

9. “Ne tot teper ya stal . . . Kuda ty, udal’ prezhnyaya, devalas” (5:16)

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840–1893): The Queen of Spades

10. “Odnazhdy v Versale” (4:44)

Armen Tigranian (1879–1950): Anoush

11. Mosi’s Aria (4:24)

Armen Tigranian: David Bek

12. David Bek’s Aria (4:25)