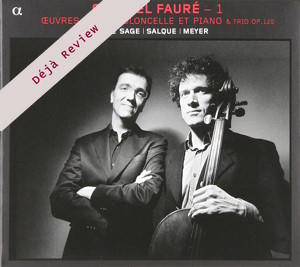

Déjà Review: this review was first published in April 2012 and the recording is still available.

Gabriel Fauré (1845-1924)

Romance, Op. 69 (1894)

Cello Sonata No. 1 in D minor, Op. 109 (1917)

Elegy, Op. 24 (1880)

Cello Sonata No. 2 in G minor, Op. 117 (1921)

Serenade, Op. 98 (1908)

Papillon, Op. 77 (1898)

Berceuse, Op. 16 (1880)

Piano Trio in D minor, Op. 120 (1922)

François Salque (cello)

Eric Le Sage (piano)

Paul Meyer (clarinet)

rec. 2011, Auditorium MC2, Maison de la Culture de Grenoble, France

Alpha Classics 600 [67]

This handsomely produced disc is the first of a five volume series of the complete chamber music of Gabriel Fauré. The pianist Eric Le Sage and cellist François Salque play Fauré’s two cello sonatas and five of his salon pieces. These artists are then joined by the clarinettist Paul Meyer to perform the Trio, Op. 120, as a clarinet trio rather than the piano trio format in which it is usually performed. The liner-notes suggest that playing it in this instrumentation points up Fauré’s kinship with the Germanic rather than the French musical tradition. I found this an interesting observation, given that his mood often recalls the more introspective of Brahms’ late piano works. This generously-filled and very well played disc shows the extent of Fauré’s achievement as a chamber music composer, and the way his music wears both romantic and modern masks.

The Romance, Op. 69, was originally written for cello and organ; the piano version goes a step up-tempo, from Andante to Andante quasi allegretto. This work is played with great expertise by Salque and Le Sage, opening with a lovely purr from the cello’s bass strings. Salque gets a chance to show off his fine legato playing, and he and Le Sage perform affectionately, without trying to make it sound more than the very superior salon music that it is.

The first Sonata begins with the tempo marking of Allegro deciso, in an unusually assertive vein for Fauré; I was reminded of the Shostakovich Cello Sonata. The slow movement features a searching theme for cello over sparse accompaniment. The midsection winds upwards in chromatic steps in a manner that is typical of Fauré’s melodies. The finale moves from a tentative-sounding start to an almost mystical level of exultation. Like most of Fauré’s later style, there is a sense of continuous flow from ostinato semiquaver figures; here it seems to anticipate minimalism. Salque and Le Sage shape the phrases with great care and wide dynamic range; they render the ceaseless shifts in feeling with the utmost sensitivity.

The Second Cello Sonata is a less outgoing work than its predecessor. It opens with a theme that has a characteristically narrow compass; this movement – along with many other tracks – show Fauré’s skill in elaborating small motifs into larger structures. The second movement is a transcription of an early Chant funéraire for wind band, and retains the repeated chordal accompaniment characteristic of a funeral march. The finale begins with rapid, rather Schumann-esque figures in the piano, while the second subject is less extraverted. Salque and Le Sage give this work a wonderfully responsive performance that shows their secure and intuitive partnership.

While writing the Trio, Op. 120, in 1922, Fauré referred to it as a trio for violin or clarinet, piano and cello. He then appeared to abandon the alternative clarinet version, completing the work the following year as a piano trio. Le Sage and Salque feel that the original conception of the work justifies its being performed as a clarinet trio, and they are joined for this purpose by Paul Meyer. I felt that Meyer’s first entry was tonally a little too bright; however, he soon blends successfully with the other parts, and one becomes accustomed to hearing a reed instrument in the ensemble. The first movement is dominated by a theme based on the tonic arpeggio; it has an economy that marks it as one of Fauré’s most masterful. The slow movement opens in a typically not quite untroubled mood; this develops into an intense episode in which the clarinet and cello play, in unison, a lamenting theme that winds upwards in remorseless chromatic steps. The finale is more animated, with a questioning theme on clarinet and cello drawing an answering fusillade of semiquavers from the piano. This is contrasted with a chorale-like theme on the clarinet and cello; the discussion of these episodes concludes with an exultant coda. Meyer is a sensitive player who combines well with Le Sage and Salque in this version of the Trio. I personally prefer the original scoring of this Trio; even a player as good as Meyer has to breathe occasionally, and this breaks the phrases up more than a bow change on a violin. Nonetheless, this is a very persuasive performance that shows a familiar masterpiece in a new light.

Between the Second Cello Sonata and the Trio, Salque plays three of Fauré’s shorter pieces for cello and piano: the Serenade, Op. 98, Papillon, Op. 77, and the early Berceuse, Op. 16. These little pieces all show Fauré’s skill at creating atmosphere and spinning out melodies, and the performances are admirable in every respect. Salque does not have a huge sound, but produces it easily, with an attractively rich tone, particularly on his lower strings. Credit should also go to Le Sage for his skills as an accompanist, adroitly managing Fauré’s continuous semiquaver writing so that it never sounds monotonous. The recording is quite close, but free from grunts or other extraneous noises; the sound picture has natural warmth, and is well balanced.

Paul Tortelier and Eric Heidsieck recorded the Fauré sonatas in the 1960s; these have become classic accounts. The rapport between the two has the confidence of a long partnership, and Tortelier sounds as if he has this music in his blood. After hearing the Salque performances I noticed a more nasal and resinous character to Tortelier’s sound, and felt that Salque produced his upper register a little more easily. The timings are similar, except for the finale of the first sonata, which Tortelier got through in 5:24 as against 7:40 for Salque; this is probably due to the latter observing a repeat which Tortelier did not.

Jean-Philippe Collard, Augustin Dumay and Frédéric Lodéon recorded the Trio Op. 120 in 1976 or 1977 in its familiar piano trio version. Their approach is more romantic, even abandoned, than on the Alpha disc; the long crescendo in the slow movement is taken very gradually. The finale in particular draws some patches of unattractive tone from Dumay, and he and Lodeon’s bow changes can be rather heavy. This performance has a great deal of conviction, but with twenty-five recordings currently available from Arkiv, there are probably smoother sounding accounts to be had.

Guy Aron

Help us financially by purchasing from