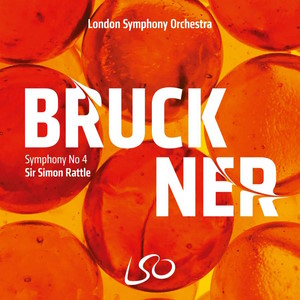

Anton Bruckner (1824-1896)

Symphony No. 4 in E-flat Major ‘Romantic’ (Version 1878-1881; Cohrs A04B)

discarded Scherzo and ‘Volksfest’ Finale (Cohrs A04B–1 & 2)

London Symphony Orchestra/Sir Simon Rattle

rec. live, 5 October 2021, Jerwood Hall, LSO St Luke’s, London

First recording

LSO LIVE LSO0875 SACD [2 discs: 126]

The first time I encountered Simon Rattle conducting Bruckner was in a live radio transmission of the Seventh Symphony with the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra in the late 1980s. At the time, the conductor would have been in his early thirties and although he had already performed the work, albeit as a percussionist with the National Youth Orchestra of Great Britain in concerts led by Rudolf Schwarz, Anton Bruckner was not a composer you would usually have associated with him then. Nonetheless, I remember my younger self concluding that the performance was impressive in parts, but slightly less inspired in others, an impression that remained some years later when he took the same work into the studio for EMI, once more with the CBSO. Since then, Bruckner has appeared with a degree of regularity in Rattle’s concert and recording programmes, the Fourth being set down for EMI with the Berlin Philharmonic in 2006, which I thought featured fine playing and recording but a rather anonymous interpretation. Much, much better was the following release of the Ninth Symphony in 2012 which not only contained a very fine account of the standard three movement work, but also had probably the most persuasive account of the newly restored final movement, too; it is a recording all Brucknerians should own. Two recordings of the Eighth were then made: one live with the Australian World Orchestra in 2015, swiftly followed by another with the LSO in 2017, before an idiosyncratic Sixth was set down with the LSO with a controversially fast opening movement – and now this re-recording of the Fourth Symphony taken from live concerts in 2021.

Perhaps one of the justifications for this new recording is Rattle’s ongoing exploration of the Bruckner canon under the aegis of Dr Benjamin-Gunner Cohrs and his revised Anton Bruckner Urtext Gesamtausgabe editions of all the Bruckner symphonies. It is at this point that any reviewer worth his or her salt has to take a deep breath and attempt, in a way both succinct (difficult) as well as interesting (very difficult), to give the reader some context of this new edition within the dizzying history of the various editions of this symphony, which consists of not just three official versions of the score, but also an additional four recognised variants. I have done my best below:

Version I: Bruckner spent most of 1874 composing his Fourth Symphony and finished it that November, although this version was never published or performed during his lifetime. Older readers may well be familiar with this score, referred to as the Original Version, via a recording of it made by Eliahu Inbal and the Frankfurt Radio Symphony Orchestra from 1982 which was released by Teldec. The composer made some further revisions to the score in the hope of a public performance in 1876, which unfortunately did not materialise. This ‘revised original’ version was both premiered and recorded in November 2020 by Jakub Hrůša with the Bamberger Symphoniker.

Version II: Bruckner returned to the score after completing his Fifth Symphony in 1878, this time thoroughly revising the first two movements and replacing the original finale with a new movement entitled Volksfest (“Popular Festival”). In December that year, Bruckner then replaced the original Scherzo with a completely new movement, which is sometimes called the “Hunt” Scherzo (Jagd-Scherzo), which is the one most listeners will recognise as being used today. Having completed his String Quintet in F Major the following year, Bruckner then revisited the Fourth Symphony once more and decided to discard the Volksfest finale by replacing it with a substantially revised reworking of the original final movement – and this is now the score which forms the basis of the Robert Haas edition of the symphony.

Further revisions followed, including a twenty-bar cut in the andante, as well as a shortened and reworked transition at the end of the development in the final movement. This score was used for the premiere and Bruckner was insistent that the changes (i.e. cuts) were observed for the second performance, too; this version forms the basis of Benjamin-Gunner Cohrs’s edition used in this new recording conducted by Simon Rattle.

A couple of years later when Anton Seidl decided to take the work to New York, Bruckner made a few further minor revisions, the most notable being for the third and fourth horns during the coda of the finale; it appears as if the cuts were restored as well. This version forms the basis of the Leopold Nowak edition.

Version III: With the ‘assistance’ of Ferdinand Löwe and probably also Franz and Joseph Schalk, Bruckner thoroughly revised the symphony again during 1887 and 1888 with a view to having it published; it was this score that received the famous, but nonetheless triumphant, performance by the Vienna Philharmonic under Hans Richter in 1888. Further minor revisions were subsequently made before the score was eventually published, for the first time, in 1890. It was this version of the score which prevailed in concert until Robert Haas published his own edition in 1936 (revised 1944) and you can still come across it in historical recordings of this symphony, most notably conducted by Hans Knappertsbusch and Wilhelm Furtwangler. I think any listener encountering this version of the symphony for the first time, having been more familiar with the Haas and Nowak editions, may well find eyebrow-raising the almost indecently exuberant use of cymbals and triangle employed in this version – probably as much tenfold more times than in all the other symphonies by Bruckner put together; as a result, for many years after the publication of the Robert Haas edition this version of the score was viewed as discredited. In spite of this, in 2004 the International Bruckner Society of Vienna under its editor, Benjamin D. Korsvedt, concluded that this was the definitive version of the score as it was effectively the composer’s final words on the work, whether or not he had been unduly influenced by well-meaning friends and associates. This version was recorded by Osmo Vänskä and the Minnesota Orchestra for BIS and I saw Vänskä perform it in concert shortly thereafter in an (in)famous concert with the London Philharmonic Orchestra in 2011 where, after a dazzling first half featuring Tchaikovsky’s Violin Concerto with Janine Jansen, the Korsvedt version of Bruckner’s Fourth was presented after the interval with little warning (it was just advertised as “Bruckner Symphony No 4”), resulting in a member of the audience storming out between one of the movements, shouting at the conductor and orchestra.

What we therefore have on this two CD set is a performance of Version II, with the cuts in the Andante, as well as in the final movement. On the second disc, there are standalone performances of the Volksfest finale, as well as the scherzo that was ultimately discarded in favour of the standard “Hunt Scherzo”, along with the unabridged versions of the Andante and the final movement, even though they total only an extra three and a half minutes more music than in the main performance. To my mind, there is something of a missed opportunity here, whereby with the (relatively) modern advances in recording technology I feel that it would have been just as easy to have had the missing music tracked separately within the main performance, rather than performed whole and separately placed on the second disc. Although the ever-delightful Dr Cohrs points out, in his notes in this release, that the listener now has the chance to hear the two different versions side-by-side, since this can only be achieved with some dexterous swapping of discs between movements, one cannot help but think if they had utilised the tracking potential of compact discs instead, let alone downloads, then even more music could have been included in this two CD set, thereby making it extra-desirable. I cannot help but conclude that what we have instead is something of a missed opportunity.

That these performances are all taken from live performances also deserves both mention and commendation, not least for the sound which ducks the bullet of the dry acoustics of London’s Barbican Centre (the LSO’s usual concert venue) by relocating to St Luke’s Jerwood Hall with an astonishingly quiet audience, even if I have to point out that the sonics on the recent recording of the same piece by Andris Nelsons and the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra for Deutsche Grammophon have even greater depth and amplitude. Nonetheless, it appears that these were concerts designed to both entertain as well as educate, by prefacing a performance of the whole symphony with a first half of the discarded Scherzo from 1874/75, the Volksfest finale, as well as the unabridged Andante and final movement. I have nothing but praise for such an endeavour and have no doubt that the concerts were a resounding success. However, what might have been a fine night out at the concert hall does not necessarily translate into something worthy of preserving on a recording for posterity, especially on a double-album, albeit one at mid-price.

Indeed, the performance of the symphony by Rattle is a lean and speedy one, with the timings of virtually each movement usually at least a couple of minutes faster than in his previous recording with the Berlin Philharmonic (even when allowing for the new cuts in the revised Cohrs edition of the score). The problem is however, that at these tempos Rattle leaves himself little time to tease out the poetry and mystery within the music which are, as a consequence, skated over. I believe most listeners may feel somewhat short-changed by this performance’s underwhelming opening, with those haunting horn calls devoid of any of the romanticism that gives this symphony the sobriquet ‘The Romantic’. Nor is the sound of the London Symphony Orchestra especially grand, technically superb thought they may be, something I am not sure is a decision by Rattle, or a characteristic of an orchestra that does not enjoy that depth of sonority which appears to be the birth-right of those great central European ensembles of Dresden, Leipzig, Berlin, Vienna and Amsterdam. Either way, this lack of grand sonority allied to the swift tempos, makes this performance of the symphony sound somewhat less impressive than it usually is. In the end, I concluded that I am not sure if Rattle really has much to say about the music in an interpretation that is just swift and fast – as early as the thirteenth bar (mercifully in whichever score/edition you happen to be using), the switch between D-flat to C by tremolando cellos and basses is exaggerated, while further on in the final movement some of the string-only passages teeter on the brink of inaudibility, none of which are for any apparent musical reason. It is as if Rattle, indisputably a fine and intelligent musician, is looking for things to say in this symphony whose magic is more intuitively realised by other, more natural Bruckner conductors. Indeed, if I ultimately conclude that Rattle’s earlier recording with the Berlin Philharmonic is a stronger recommendation than this LSO remake, even if only for the more grand and authentic sound of the orchestra, it is with the caveat that it is also the weakest entry into the lineage of Bruckner Fourth Symphony recordings made previously by the Berliners with Eugen Jochum, Herbert von Karajan (twice), Daniel Barenboim and Günter Wand.

To conclude, if you must have Rattle in this symphony, then the Berlin PO recording is the one to get; if you must have the London Symphony Orchestra, then I would point you in the direction of Bernard Haitink’s live 2011 reading (again on LSO Live) as being an altogether more profound experience than anything offered on this new release. If you are interested in the various different movements that were discarded by the composer during his struggles with composing this symphony, then may I suggest that various recordings by Gerd Schaller, Georg Tintner and Jakub Hrůša as all being more satisfying than Rattle’s zippy run-throughs. As for the symphony itself, the established favourites of Böhm, Karajan, Wand and Blomstedt (in Leipzig), with Celibidache’s astonishing and revelatory account, live with the Munich PO (on Warner Classics) as a long-breathed outlier, are not disturbed by this new recording by Simon Rattle. Perhaps what sums it all up is the enclosed booklet, so thick is impossible to remove from the jewel case without it being damaged, which contains copious – and arguably superfluous – information on Bruckner, the symphony, Simon Rattle, the London Symphony Orchestra (including a full personnel listing), all in various languages with photographs, but only allows Dr Benjamin-Gunner Cohrs two short paragraphs to write about his new edition of the score, surely this recording’s raison d’être; in the end, I felt it was yet another missed opportunity.

Lee Denham

Previous review: Ralph Moore (October 2022)

Help us financially by purchasing from

Contents

Disc 1:

Symphony No 4 in E-flat Major, ‘Romantic’ (Version 1878–81; Cohrs A04B) [61:32]

1. I. Bewegt; nicht zu schnell (1881) [17:37]

2. II. Andante quasi Allegretto (1881) [15:23]

3. III. Scherzo. Bewegt – Trio. Nicht zu schnell. Keinesfalls schleppend – Scherzo da capo (1881)

[10:53]

4. IV. Finale. Bewegt; doch nicht zu schnell (1881; abridged) [17:39]

Disc 2:

Symphony No 4 in E-flat Major, ‘Romantic’ (Cohrs A04B) [65:05]

1. [Discarded] Scherzo. Sehr schnell – Trio. Im gleichen Tempo – Scherzo da capo [11:55]

(1874/rev. 1876; Cohrs A04B–1)

2. [Discarded] Finale (‘Volksfest’). Allegro moderato (1878; Cohrs A04B–2) [15:48]

3. Andante quasi Allegretto (1878; extended initial version)] 16:37]

4. Finale. Bewegt; doch nicht zu schnell (1881; unabridged) [20:45]

Performed in the Urtext Edition by Benjamin-Gunnar Cohrs, newly published

by Alexander Hermann Publishing Group, Vienna 2021.