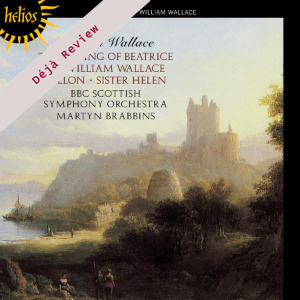

Déjà Review: this review was first published in February 2000 and the recording is still available.

William Wallace (1860-1940)

Sir William Wallace

Villon

The Passing of Beatrice

Sister Helen

BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra/Martyn Brabbins

Originally released and reviewed as Hyperion CDA66848

Hyperion CDH55461 [72]

Like MacCunn, Wallace (1860-1940) was a son of Greenock and as with almost all of the composers of the time was from a privileged background. But, despite being born with the silver knife and fork on his plate (which can sometimes mask unwarranted artistic indulgence), he was clearly a genuinely gifted individual; a bit of an all round clever Richard in fact: trained as a doctor specialising in ophthahmology, he also dabbled in Classical Scholarship, wrote poetry and drama, and painted, and to boot served in the Royal Army Medical Corp during the First World War.

In the end, however, it was music that came to take precedence in his life both as a composer and a writer. He studied under Mackenzie at RAM, becoming friends with his fellow, younger student and, to my mind, the most outstanding composer of that generation, Granville Bantock. He was obviously a man whose bonnet could buzz with some restive bees as Bantock’s letters reveal how he was apt to throw china round the kitchen in the heat of an argument; though the younger man admired and did much to promote his music.

Wallace eschewed his own country, preferring to live in London for the sake of his career: yet, as with his re-domiciled Professor, Wallace’s compositions are almost totally forgotten today, and this is a genuinely enterprising restoration-act by Hyperion. Indeed the sleeve claims the first ever commercial recording of any of Wallace’s works. Listening to this CD the stature of Wallace’s music becomes immediately evident and it is a wonder how such obviously exhilarating and rapturous music could have so easily fallen into neglect: finely constructed, filled with charmed orchestral writing, it reveals a sincere and affecting musical personality.

George Bernard Shaw once rightly observed that Wallace had ‘a very tender and sympathetic talent’, but typically also advised that Beatrice be cut by nine-tenths. Shaw could be as inanely flippant as he was clever, and was often more intent on being amusingly droll than showing a necessary critical empathy with the subjects of his acute wit. Wallace’s music is undoubtedly of its time (an often lazy critical artifice – so of course was Bach’s, Mozart’s, and Beethoven’s), and oozing the still less than fashionable effusive romantic musical rhetoric of late-Victorian and Edwardian British music.

More hard-bitten commentators will clearly discern a certain diffuse quality in Wallace’s work again this was part of the very charm of the music of the period. (It is perhaps worthwhile noting that both Bantock and Wallace were considered ‘difficult’ in their own time – too radical for one age, soon too conservative for another – and that furthermore many of the decidedly ‘unromantic’, say Schoenberg-influenced, composers who came for a period to dominate British music are now also all but forgotten.) Shaw’s remark is just plain tommyrot.

The Passing of Beatrice is an inspired work, moving and evocative throughout, with an exquisite orchestral touch and deserves to be a standard part of the repertoire of British music.

Sir William Wallace was written to mark the 600th anniversary of the death of the ‘Scottish hero and freedom-fighter; beheaded and dismembered by the English’. It has a tender lento opening before becoming more dramatically involved in its subject with the sustained tension of that evocative orchestral exposition so associated with the ‘romantic’ idiom, including some exquisitely pleasing moments. Scots wha’ hae provides thematic material, but, in an unusual structural tum-about, is not fully stated until the finale. It is a fine and affecting piece which repays a concentrated ear.

Villon, the last written of these four symphonic poems, published in 1910, is a marvellous evocation of the French ‘rebel-poet’ and perhaps the most immediately satisfying of the four symphonic poems with some memorably fertile scoring. After a marvellous opening and clever employment of the bassoon, the music unfolds into a gripping and ever-changing piece, with light touches and elegiac tempers, contrasting with passages of sensuous exhilaration, at times rising to climaxes of telling intoxication. It is one of the highlights of the whole series.

The final piece, Sister Helen, inspired by Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s poem, equally reveals the abiding stature of the composer and another forcibly fervid musical characterisation.

Whilst the neglect of the music of MacCunn, Mackenzie, and Wallace is not unduly beyond the unfathomable, and hardly as unjustifiable as in the case of say Granville Bantock, it is a joy at last to hear this forgotten but more than worthy music played with such enthused commitment. It is abidingly picturesque, passionate, warm-hearted, and unpretentious. Yet, though these were evidently characteristically Scottish spirits at work, they were unable to achieve an overwhelmingly distinctive national focus in their music. For all the intrinsic and satisfying musicality, the conventions of their musical language still very much looked outward to Europe and remained very much bound within the strictures of the academy as opposed to springing from the roots of Scottish folk music, disenabling them to establish – as one now, a century on, would have liked – a more radical and truly culturally diagnostic classical music.

The works of Wallace are truly resplendent and, performed by an orchestra thoroughly immersed in the heart of the composer, provide perhaps the most demonstrably soul-subduing musical experience.

Vincent Budd

Help us financially by purchasing from