The Galant David Rizzio – Eighteenth-century arrangements of traditional Scottish songs

Makaris

No recording details supplied

Texts included

Reviewed as a stereo 16/44 download with pdf booklet from Naxos

Olde Focus Recordings FCR921 [74]

Most ‘classical’ music performed today in churches and concert halls all over the world, and recorded on disc, belongs among the category of what is called ‘art music’. It was written by composers and has come down to us in fixed form, either in manuscript or in printed editions. However, in the course of history, much music – and probably even most – was sung and played by people who did not use any written notes; many of them were probably not even able to read music. Improvisation was the name of the game, and music was handed over from one generation to another orally. It had no fixed form, and in the course of time, both texts and music often changed considerably. In most cases their original forms are not known, unless at some time such music was written down. That is the case with the music which is the subject of a recording by an ensemble that calls itself Makaris.

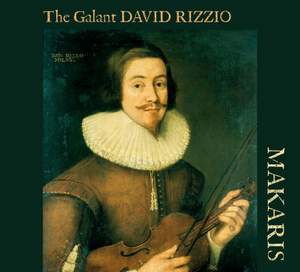

The booklet explains the name thus: “A makar (pl. makaris) was a royal court troubadour of medieval Scotland; the term was resurrected centuries later and is used now to describe a Scottish bard or poet.” This makes clear where the music performed on this disc comes from. There is something curious about the repertoire, though. On the frontispiece we see the portrait of a gentleman, whom nearly everyone will immediately recognize as having lived in the 16th century. The title of this disc includes his name: David Rizzio. On the second page of the booklet we read: “David Rizzio, secretary and consort to Mary, Queen of Scots and the Mystery of the Music most bizarrely and falsely attributed to Him long after his infamous Murder here performed by Makaris”.

David Rizzio was of Italian origin. In 1561 he travelled to Scotland in the service of the Duke of Savoy’s ambassador. He entered the service of Queen Mary as a valet and a bass singer, and soon became her private secretary. That caused concern among Mary’s Protestant opponents, and in 1566 he was murdered before the Queen’s eyes. What may Rizzio have to do with Scottish traditional music, especially as there is no indication whatsoever that Rizzio has ever written any note of music? That is all due to William Thomson (c1684-c1762), who in 1726 published a collection of songs under the title of Orpheus Caledonius. It was the first printed edition of arrangements of traditional Scottish songs, consisting fifty settings by Thomson over a figured bass. For 43 melodies no composer was mentioned, and it is likely that Thomson plagiarized their texts from a book of Scottish poetry published two years before. Thomson attributed the seven remaining melodies to David Rizzio.

What may have been the reason for Thomson to do this? Kivie Cahn-Lipman, in his liner-notes, suggests that he may have been linking up with a tradition that already existed. “However, the Italian school of composition then held sway in London, and it is likely that Thomson simply hoped to sell more copies of his publication by adding to it the name of a notorious Italian (Rizzio being a plausible choice, given that he was widely known to have been a musician who was murdered in Scotland). There could also have been a political element to the Rizzio ascriptions; the Treaty of Union had only recently united England and Scotland, and an Englishman affixing a foreigner’s name to some of the most enduring and beloved Scottish tunes might have been a response to heightened Scottish nationalism.”

In 1733 Thomson’s book was reprinted, and in that edition he had considerably changed the style of many songs, making them more easily accessible, in line with the fashion of the time, which preferred a light and simple style over ornamented songs in the Italian style. Moreover, the attributions to Rizzio had also been omitted. However, a myth is often more attractive than reality, and the one Thomson had created or at least disseminated, had been enthusiastically picked up by others, such as the music printers John Walsh and John Watts. The Scottish composer James Oswald printed a collection of Scottish tunes in 1742 and attributed several of them to Rizzio as well. Even some of the great composers fell for it. Francesco Geminiani, who arranged a number of Scottish songs, called Rizzio even one of history’s greatest composers, alongside Jean Baptiste Lully.

However, in the second half of the 18th century doubts were vented about Rizzio’s contributions to music. Some authors pointed out that some tunes existed before Rizzio had arrived in Scotland. One author wrote: “That a young dissipated Italian busied in the intrigues of a court … could in a few years have disseminated such multifarious compositions through a nation, which despised his manners and hated his person, is utterly incredible”. Despite this, the Rizzio myth helped to generate a widespread fascination with Scottish mythology and culture. Ironically, the arrangements by the likes of Haydn and Beethoven may never have been written if the Rizzio myth had not existed.

The present disc presents all 22 songs falsely attributed to Rizzio, in various arrangements, mostly by composers from the 18th century, but also by members of the ensemble. Most of them are performed in a combination of voice and instruments, and some are performed in instrumental versions. In some cases, arrangements by different composers have been mixed. The only composer who is represented with original music, is James Oswald. The longest piece from his pen is A Highland Battle, a piece in a long tradition of battaglias, but then with entirely different instruments.

As far as the arrangements are concerned, two of the best-known of the composers who made such pieces are the above-mentioned Geminiani and Johann Christian Bach. Francesco Maria Veracini, the Italian violin virtuoso, who also visited England, wrote a movement with the title of Scozzese in the Sonata No. 9 from his collection Sonate Accademiche. Haydn is represented with The Flowers of Edinburgh. Among the lesser-known composers are Samuel Arnold, William Shield, the Italian-born Domenico Corri and the Scottish composer Alexander Munro.

This disc seems to me of great interest to any lover of traditional music. What we have here is the performance in historical fashion – with instruments of the 18th century – of music from a stage in its development in which it was fixed. It is not only an interesting contribution to our knowledge of the music scene in 18th-century England, but also the history of traditional music and the way it developed in the course of time.

Those who have a more than average knowledge of Scottish music may recognize many pieces in different fashions, from a later period. Those who have no thorough knowledge of English, let alone Scottish culture, may find it hard to really understand what these pieces are about, as the texts are often hard to grasp. The liner-notes are very informative, and at the end of the booklet one finds no fewer than 108 explaining notes, but reading the texts and these notes in a digital booklet is a bit of a pain in the neck. Anyway, even if you don’t understand all the texts, this is an enjoyable disc, as the members of the ensemble perform these pieces with audible enthusiasm and technical skills on their respective instruments.

Johan van Veen

www.musica-dei-donum.org

twitter.com/johanvanveen

Help us financially by purchasing from

Contents

The Broom of Cowdenknowes (arr. Johann Christian Bach (1735–1782), W.LH 2)

Black Eagle – Drouth (arr. James Oswald (1710–1769))

Down the Burn Davie (verses arr. William Thomson (c.1684–c.1762); instrumental interlude arr. Joshua Campbell (c.1730–1801))

The Lass of Peaty’s Mill (arr. Francesco Geminiani (1687–1762))

Pinkie House (arr. Charles McLean (c.1712–c.1772))

Roslin Castle (arr. Pietro Urbani (1749–1816))

Fickle Jenny (anon; first published in British Musical Miscellany: or, The Delightful Grove (1734))

The Lowlands of Holland (arr James Oswald) – Gigg (?James Oswald) – Leslie’s March (arr. The Musical Miscellany (1731))

Beneath a Beech’s Grateful Shade (verse arr. Musical Miscellany; instrumental passages arr. William McGibbon (1690–1756))

Push About the Brisk Bowl (James Oswald)

Tweed Side (arr. Francesco Maria Veracini (1690–1768), Sonate Accademische, op. 12,9, III: Scozzese (excerpt))

Beneath a Green Shade (arr. Johann Christian Bach: The Braes of Ballanden, W.LH 1)

The Bush Aboon Traquair (vocal setting arr. William Shield (1748–1829); instrumental parts arr. Alexander Munro (1697–1767))

The Yellow-Hair’d Laddie (arr. Burke Thumoth (fl. 1739–1750))

Auld Rob Morris (verses arr. Samuel Arnold (1740–1802); instrumental interlude arr. Francesco Geminiani)

An Thou Were My Ain Thing (verse arr. Domenico Corri (1746–1825); instrumental interlude arr. Francis Peacock (1723–1807))

The Last Time I Came O’er the Moor (verses arr. James Oswald; instrumental coda arr. Francesco Geminiani)

A Highland Battle (James Oswald)

The Flowers of Edinburgh (verse arr. Franz Joseph Haydn (1732–1809) H XXXIa,90; traditional instrumental reel arr. Caitlin Hedge as coda)

William’s Ghost (arr. Paul Morton and Doug Balliett)

Love in Low Life (composed by ?James Oswald; traditional instrumental jig Haste to the Wedding, arr. Caitlin Hedge as interlude)

The Boatman (arr. Manami Mizumoto)

The Cock-Laird (arr. Doug Balliett)

Peggy, I Must Love Thee (harpsichord part arr. Adam Craig (c.1730); additional instrumental music by Elliot Figg)

Bessy Bell and Mary Gray (verses arr. Fiona Gillespie and Paul Morton; vocal interludes arr. James Oswald, instrumental interlude/coda arr. William McGibbon)

Dances from Queen Mab (?James Oswald)