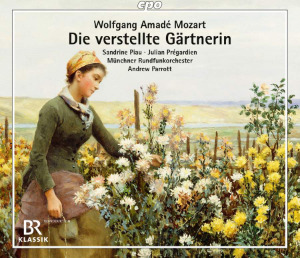

Wolfgang Amadé Mozart (1756-1791)

Die verstellte Gärtnerin, K. 196 (1779/1780)

Sandrine Piau – Sandrina/Countess Violante Onesti (soprano)

Susanne Bernhard – Arminda (soprano)

Lydia Teuscher – Serpetta (soprano)

Olivia Vermeulen – Ramiro (mezzo-soprano)

Julian Prégardien – Count Belfiore (tenor)

Wolfgang Ablinger-Sperrhacke – Don Achise, Podestà (tenor)

Michael Kupfer-Radecky – Nardo/Roberto (baritone)

Münchner Rundfunkorchester/Andrew Parrott

rec. 2017, Prinzregententheater, Munich

German libretto [arias and ensembles only] with English translation and commentary in German and English included

CPO 5553862 [3 CDs: 188]

I regret having missed the performances of Die verstellte Gärtnerin on 21 and 22 January 2017 at the Prinzregententheater in Munich during which this recording was made, but am delighted that an audio document with high production values has been issued. Opportunities to see this Dramma gioccoso live in the theatre eluded me until 27 January 2023, when I savoured the work in its original incarnation as La finta giardiniera at the Salzburger Landestheater, a performance that I reviewed for Das Opernmagazin.

Wolfgang Amadé Mozart likely transformed La finta giardiniera, which received its premiere on 13 January 1775 at Munich’s Salvatortheater, into a Singspiel in collaboration with Johann Heinrich Böhm, whose travelling group of actors arrived in Salzburg in September 1779. In one of the most successful adaptations of vocal music from one language into another, the translation, probably by Johann Franz Joseph Stierle, renders the Italian libretto into idiomatic German that fits the music perfectly. The spoken dialogue followed the content of the recitatives and made the story accessible to Böhm’s audiences, initially in Augsburg and subsequently in other German cities.

The Singspiel adaptation kept this opera in the active repertoire during Mozart’s lifetime. In spite of the first audience’s enthusiasm, La finta giardiniera fell into oblivion after a mere two further performances. As with the critical reception of La clemenza di Tito, which was seldom performed during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, neglect does not mean that this comic opera by the eighteen-year-old Mozart is unworthy of a place on operatic stages. Both the libretto, presumably by Giuseppe Petrosellini, and Mozart’s music offer characters and situations with greater psychological and emotional depth than many of the most frequently performed works in the current repertoire.

In my review of Lucio Silla from June 2022, I explained that early Mozart operas have suffered from obstinacy by audiences resistant to admitting operas into the ‘canon’. The often-repeated trope that Die verstelle Gärtnerin portends his subsequent achievements does not do this opera justice. Mozart’s use of the orchestra not only to establish the ‘mood’ of arias and ensembles, but to ‘comment’ on the sung text (e.g., in the arias by the Podestà, Act 1, no.3, Nardo, Act 1, no. 5, and Sandrina, Act 2, no. 21) was innovative for its time and all the more impressive considering the modest-sized ensemble at his disposal.

The libretto combines seriousness and parody like many late-eighteenth–century Opere buffe: each figure expresses genuine emotion while parodying literary and theatrical conventions. Sandrina/Violante is excessively forgiving and empathetic with Belfiore, who attempted to kill her in a fit of jealousy; Serpetta is coquettish and absurdly difficult to please; and the Podestà nearly has a nervous breakdown in his Act 3 aria (no. 25) because he cannot obtain Sandrina’s hand in marriage. One strikingly effective use of irony occurs in the Podestà’s Act 1 aria (no. 8) in which he delineates his purported forebears, including Greek and Roman heroes. His ridiculously inflated heritage is a wry commentary on a society in which hereditary titles are more important than achievements (literary parallels are found in Pierre Augustin Caron de Beaumarchais’s Le Barbier de Séville ou La précaution inutile and La folle journée ou Le mariage de Figaro).

Mixtures of profundity and humour, especially within individual musical numbers, vanished in the early nineteenth century (some of Gioachino Rossini’s operas are exceptions) and have rarely returned. Appreciation of eighteenth-century operas requires understanding (and acceptance) that joy and sadness can (and often do) coexist in literature and real life. This juxtaposition also occurs in Jane Austen’s Sense and Sensibility (1811) in which two sisters, Elinor and Marianne Dashwood, epitomise two types of intentionally exaggerated personalities: Elinor is a satire of the extreme rationality found in some ‘Enlightenment’ philosophy, while Marianne reflects excessive emotionalism (cf., Henry Mackenzie’s The Man of Feeling, published in 1771).

To the best of my knowledge, the present recording is the first of Die verstelle Gärtnerin since Hans Schmidt-Isserstedt’s undertaking for Philips in 1972, which was included in The Complete Mozart Edition (1991) and Mozart 225. The New Complete Edition (2006). As excellent as Schmidt-Isserstedt’s recording is, the dialogue is heavily abridged. The new recording includes most of the dialogue (alas in a modernised edition) and provides a vivid sense of being in the theatre for what was surely a convincing production (occasional laughter during the dialogue suggests the audience approved of what was happening on stage). Nearly the entire cast consists of native speakers who enunciate the text immaculately. The overall effect is thoroughly engrossing from the overture to the chorus that ends the third act.

Sandrine Piau, who sings the lead role of Sandrina (the disguised Countess Violante), conveys pathos, bitterness, forgiveness, and love for Count Belfiore with whom she reconciles. The warmth of Piau’s soprano and her embodiment of the role compare very favourably with Helen Donath on the Philips recording. The soprano Susanne Bernhard sings Arminda, the Podestà’s niece, with a degree of menace that lends credibility to the character’s moral rigidity with her betrothed Belfiore and vindictive cruelty toward Sandrina, who is in love with the Count. Bernhard injects a hair-raising level of fury into Arminda’s aria at the beginning of Act 2 (no. 13).

As Serpetta, the Podestà’s chambermaid, the soprano Lydia Teuscher is flirtatious, sarcastic, and, to a degree, harsh. Serpetta is annoyed with Nardo’s interest in her and frustrated by the Podestà’s indifference toward her. Teuscher brings a sense of humour to the role so that Serpetta does not become too sardonic (she is charming enough to maintain Nardo’s affection). Olivia Vermeulen, a mezzo-soprano, makes Cavaliere Ramiro a dejected, lovelorn young man who is hurt by Arminda’s rejection of him in favour of Count Belfiore, who is of higher rank. Vermeulen projects Ramiro’s tenderness, sadness, and, most persuasively of all, his angry outburst in the tour de force aria in Act 3 (no. 26), one of Mozart’s greatest ‘rage’ arias along with Elettra’s aria ‘D’Oreste, d’Aiace’ in the third act of Idomeneo.

Julian Prégardien makes the tenor role of Count Belfiore, who attempted to kill Countess Violante/Sandrina before the action commences, seem remorseful for his jealous outburst. Prégardien’s lyrical voice not only makes Belfiore sympathetic, it lends poignancy to the arias. As the Podestà, the tenor Wolfgang Abinger-Sperrhacke brings a sense of yearning to the Act 1 aria (no. 3) in which he compares his emotional states to musical instruments. Throughout the opera, Abinger-Sperrhacke conveys the character’s initial optimism about a prospective marriage with Sandrina/Violante and his subsequent anguish, frustration, despair, and madness as he realises that she loves Belfiore. Michael Kupfer-Radecky presents Nardo/Roberto as more than a buffo character, but rather as a humorous, well-intentioned servant to Sandrina/Violante and an ardent lover of Serpetta. Kupfer-Radecky uses his baritone voice to illustrate the character’s wit, affectionate teasing, and confident demeanour that leaves no doubt about the outcome of his wooing: Serpetta agrees to marry him at the end of the opera.

Andrew Parrott leads the Münchner Philharmoniker with a light hand and flowing tempi that maintain the dramatic tension throughout. Owing to his experience with historically-informed performance practice, Parrott helps a radio orchestra, which is renowned for its interpretations of large scale works from later eras, sound like an ensemble for Mozart. Judicious tempi, stresses, and pauses represent the atmosphere of each aria and ensemble; the modern-instrument orchestra plays with minimal vibrato and reveals Mozart’s inventive orchestration.

The three CDs are packaged in a jewel case with a handsomely illustrated booklet that contains an essay by Jörg Handstein and the libretto in German with an English translation. My only complaint is that only the sung texts are included; the absence of the spoken dialogue might hinder listeners unfamiliar with the opera from identifying who is speaking when multiple characters converse with each other. Given the paucity of recordings, I wish that the original form of the dialogue had been preserved to give an opportunity to hear what was spoken during Mozart’s lifetime. The adaptation here does not distort the story, however.

This important release adds substantial value to the Mozart discography and provides rewarding repeated listening for Mozart lovers and connoisseurs of opera in the ‘Classical’ period. It certainly counts among the finest recent operatic releases.

Daniel Floyd

Help us financially by purchasing from